Shantytowns

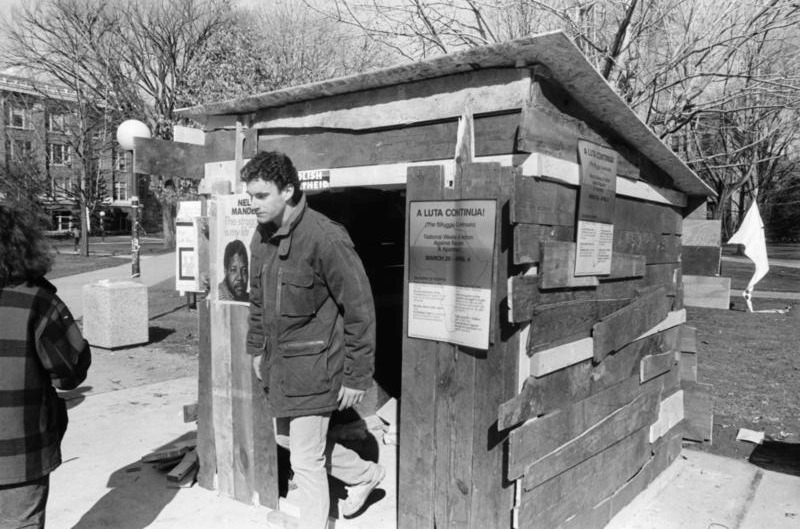

During the height of the anti-apartheid movement at the University of Michigan, students created their own shantytowns in the middle of campus in order to demonstrate the plight of South Africans. Activists reinvigorated protests during this period in response to the state of emergency imposed by the Botha regime in South Africa which had killed 2500 South Africans since 1984. The protests were part of a national movement and campuses and organizations shared some tactics in their fights for divestment. One of these tactics involved the building of shantytowns in public places on campus. Built to resemble the shanties in which many Black South Africans were forced to live, these shantytowns were visible reminders of the large division of wealth and social inequalities that existed within Apartheid South Africa. The Free South Africa Coordinating Committee (FSACC) built the first shanty in March 1986 "in conjunction with with the construction of shanties on campuses across the country." The 7x7x7 structure, situated in a corner of the Diag, was constructed with permission from the University to “remind the student body of the oppressive and inhumane conditions forced upon the South African population.” The FSACC and the United Coalition Against Racism (UCAR) built more shanties in the spring of 1987 as a part of a national two weeks of action against apartheid protest. This demonstration attempted to "further pressure the University" and "to draw parallels between the oppression of Black South Africans and people of Color in the U.S."

Unlike other college campuses where the shanties were a much more contentious issue, the fact that UM protesters sought permission for a shanty and that it was granted suggests a much calmer approach on campus. The University Record reported on March 24, 1986 that Vice President Henry Johnson granted permission as long as “. . . the project not interfere with normal use of the area.” Unlike other protests seen during this time, U of M students did not take more aggressive actions like taking over the Regents meetings or performing die-ins. In a February 2015 interview with Matthew Countryman, a leader in Yale University’s divestiture movement, Countryman explained the strategic turn to shanties as a way to engage a wide range of students which would not necessarily require a full commitment to the movement.

While this particular facet of the movement was not the most prominent in the University of Michigan protests, it was a highlight at other campuses. Shantytowns engendered so much debate and visibility that police forces were sometimes called in to disperse the collection of students. As Countryman recalled, the physical protest style of the shantytowns confronted the administration viscerally. It even provoked a personal response from the university president. Police forces were called to shut down the shantytowns, and the situation escalated into conflict between students and local police.

Anti-Apartheid and Domestic Racism

While the shanties at UM represented a less aggressive phase of protesting, the mood on campus was less calm. UCAR’s Statement of Unity condemned the “repeated violent attacks on the anti-apartheid shanty,” among other “instances of overt racism” on campus during this period, including “physical and verbal assaults” endured by non-white students and displays promoting the KKK. Activists staffed the shanties for long periods of time, but could not prevent intermittent campus backlash against the structures, which were repeatedly burned, kicked down, or peppered with racist graffiti. In one instance in the spring of 1986, a small group of vandals was caught by campus police, only to have their case thrown out by the Washtenaw County prosecutor. The same prosecutor had chosen to prosecute peaceful protestors who had occupied Congressman Pursell's office earlier in the year, provoking outrage from the activist community over the evidently skewed priorities forwarded by the prosecutor's office.

Some campus groups did advocate more aggressive action to protest apartheid and racism. One such organization was the Committee Against Racism and Apartheid (CARA). This 1986 flyer from CARA promotes a FSACC event. However, CARA criticizes the FSACC for not having “a strong program of action.” The flyer features strong language and calls on the U of M community to “rebuild the spirit of BAM [the Black Action Movement of 1970].” In addition to protesting apartheid and U.S. involvement in South Africa, CARA opposed U.S. involvement in Central America and the Middle East. Recalling BAM, CARA demanded increased minority enrollment, financial aid, and support services. In order to accomplish its demands, CARA advocated “confronting the university’s administration with direct actions such as sit-ins, tuition strikes, or a broader student-worker strike.”

Thus, as late as 1986, and continuing into 1988, the lessons of the civil rights movment in the U.S. were still prevalent in the motivations for anti-apartheid action. With the fight against racism such a potent issue on campus, the words of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. remained relevant, both domestically and abroad. This flyer, handed out by the FSACC in January of 1986 recalls Dr. King's condemnation of apartheid back in the 1960s, sustaining the connection between human and civil rights protests of the 1960s and the 1980s.

Sources for this page:

University Record, Vol. 41, No. 23

“Statement of Unity,” UCAR, FImu UCAR (United Coalition Against Racism), Subject Vertical File, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

"The Anti-Apartheid Shanties," FSACC, FSACC: Africa and South African Apartheid 1985-88, Box 3, CAAS, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

"Open Letter to Presecutor Delhey," June 15, 1986, Free South Africa Coordinating Committee, FSACC: Africa and South African Apartheid 1985-88, Box 3, CAAS, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.2015 interview with Matthew Countryman