The Art Scene at UM

Faculty and students played an active role in bringing avant-garde art to the University of Michigan and Ann Arbor during the 1960s. Initiatives including the Ann Arbor Art Festival, the ONCE group’s annual festivals, and Happenings took place around the time the University of Michigan Museum of Art was collaborating with School of Art professors to create A New Realist Supplement and bring the Guggenheim’s Six Painters and the Object to Ann Arbor. In 1961, Professor Irving Kaufman invited Alan Kaprow to Ann Arbor to organize the first Happening ever staged on a college campus (Ursprung 2016).

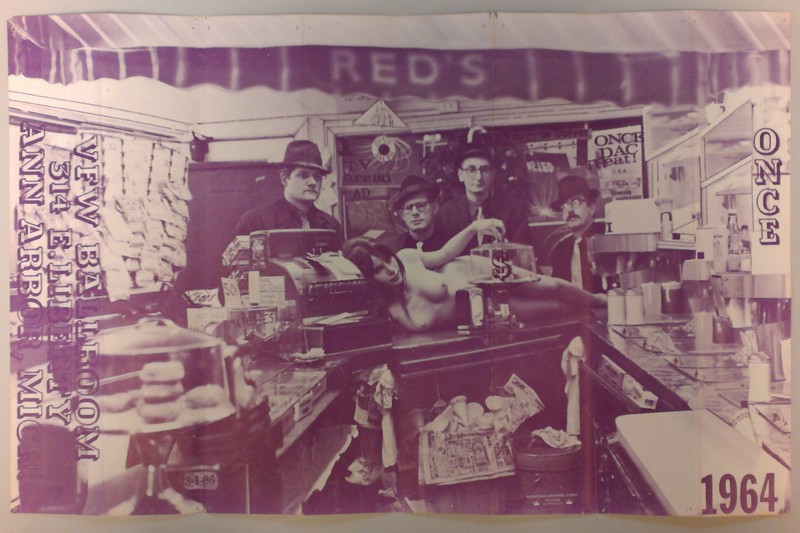

Professors Milton Cohen and George Manupelli are two of the most well-known faculty involved with the experimental art movements of the 1960s and ‘70s. Milton Cohen, a professor at the University’s School of Architecture and Design from 1957, founded the Space Theatre shortly after his arrival in Ann Arbor. The Space Theatre was a multi-sensory performance space not unlike Alan Kaprow’s “happenings.” The theatre drew other faculty and local composers together to collaborate on electronic music, including composers Gordon Mumma and Robert Ashley. These later, along with film maker George Manupelli, founded the ONCE festivals that brought together John Cage and other avant-garde composers and performers from across the United States and Europe.

In addition to his work with Cohen’s Space Theatre and the ONCE festival, George Manupelli is best known for his creation of the Ann Arbor Film Festival, a celebration and screening of indie films started in 1963 that still occurs annually.

The artist Mike Kelley, who studied at the University of Michigan in the 1970s, paid tribute to Manupelli and the Ann Arbor Film Festival in an interview with Gerry Fialka in 2004. You can view it here. The tribute can be found near the video's 50 minute mark.

-EL

Alumna Interview with Michele Oka Doner

Michele Oka Doner was a freshman art student in 1963, the year of the Pop Art exhibits at UMMA. As one of the University of Michigan’s successful alumni, Oka Doner was interviewed by researchers in the summer of 2016 as a part of the University's bicentennial project (Oka Doner 2016). In this interview the artist discussed her relationship to the art of the time, the teachers, the social climate, and feminism, and revisits her position as a young woman artist in the transition between the postwar “Silent Generation” and the Baby Boomers of the 1950s.

For Oka Doner and other aspiring artists of the 1960s, the expression “the starving artist” was generally accurate. Young artists could not afford expensive art materials for their work, a problem relieved in part by contemporary art trends like the use of found objects. Oka Doner explained, “Constructs and found objects were joyful because they didn’t cost anything”, and their use in art was encouraged by UM art faculty willing to break with more traditional methods of art instruction.

Oka Doner’s relationships with fellow classmates and teachers connected her not only within the university community but with the broader scene in Ann Arbor. In her words, “No one else I knew on campus was having such a good time as we were in the art school.” She worked closely with George Manupelli, the founder of the Ann Arbor Film Festival. Through these relationships she was introduced to experimental artists like Andy Warhol and the Velvet Underground when they performed at the university in 1967.

The teacher-student relationship that Oka Doner describes is one that is very different from that experienced by today’s undergraduates. “I remember Oldenberg’s visit really well because we all hung out at [Manupelli’s]…the teachers let us hang with them…” Relationships that would be deemed inappropriate, or at least controversial, today had a strong, eye-opening influence on Oka Doner as a young woman.

“It was really fun…we were really kids, really innocent in a way kids can’t be anymore because they have the Internet and they know too much. We were really a bunch of nice kids but we were willing to listen and learn and change the world. They said they were gonna do a happening, and they did one all the way out (by the) stadium. I didn’t know what a happening was. We went in a house, and it was dark and you couldn’t see anybody. You sorta knew who was there, and you smelled rotten eggs. I guess they put sulfur in the window. You weren’t worried that someone was going to slip LSD in…we didn’t know about it.”

According to Oka Doner, Ann Arbor serves as a proving ground for new artists and new forms of expression. Exhibitions like A New Realist Supplement gave space for experimentation that helped to galvanize art movements that eventually became internationally recognized.

…this was a body of work that challenged the New York school of abstract expressionism. How does one do that? My husband said that no matador goes right to Madrid, he goes to the small rings outside. My contention is that Ann Arbor has always been the small ring where you go and try out your ideas or things and you’re in a safe place.”

At a moment in time when post-war conservatism emphasized conformity, Oka Doner was a part of a generation of feminists, activists, and artists pushing against “those coy, Mary McCarthy people that were smug and not telling. The older siblings [as] I call them.” The older siblings did not have the rebellious mindset that the abstract expressionists and modern artists incorporated into their work. They didn’t have the open mindset towards sexuality and drugs that the 60s was to offer younger women. To be a woman even a few years before 1963 was much different than to be one in 1963. Women’s position in society was beginning to face radical challenges. “We broke it down, we opened doors, and even with the pill—the pill came out my freshman year…there’s this pill and we can get it legally…”

In a male dominated society and on a male dominated campus, young female artists like Oka Doner felt the pressure and personal obligation to work harder to compete with their male classmates. For Oka Doner, that sometimes limited her social engagements with her peers.

“And I remember the day, and I remember I was sitting where I was when somebody came in with Hashish…I was trying to look like I knew everything but it was really ….I wasn’t gonna smoke it, but they all smoked it, and, you know, I had my limits as to how transgressive I was gonna get, I had things to do. I was really very engaged with my work and that was a distraction. It wasn’t a moral thing - it’s just I wasn’t looking for purpose. I had a definite purpose. Also, being a woman, I had more to prove. Being a woman in those years…and to want to occupy a primary space, nothing marginalized, I had a lot of work to do to keep all that going.”

- Hannah Sharpe, EL