Pop and New Realism in 1963

What was Pop Art and New Realism?

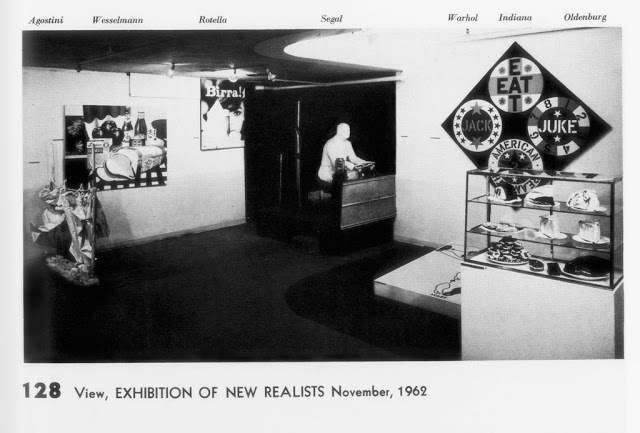

The two related trends were introduced to a broad American public in late 1962 through a much-discussed exhibition at the Sidney Janis Gallery. It was this exhibition that probably inspired Samuel Sachs II, an art historian who was about to take the job as Assistant Director at the University of Michigan Museum of Art, to eventually propose an exhibition of Pop Artists and frame its companion as A New Realist Supplement.

New Realism

The term “Nouveau Réalisme” arose in the late 1950’s and early 60’s to describe an art movement pioneered by French and European artists who expressed their negative reactions to abstraction, as well as the growing consumerism in post-war Europe. In an attempt to bring art closer to life, their work focused on adapting actual objects as a way to convey everyday reality without idealization, incorporating everyday materials through assemblage, collage, and performance. With the critic Pierre Restany, they issued a manifesto in 1960, then spread internationally as the group exhibited in several locations, including the New Realist show at the Sidney Janis Gallery in New York. At the time, the boundaries between Pop and New Realism were unclear, and reactions to the art were mixed. Janis saw both groups as part of a significant art movement, calling them “factual artists” (Janis 1962), but faced severe backlash from several artists including the abstract expressionists Mark Rothko, Phillip Guston, Adolph Gottlieb, and Robert Motherwell, who all left his gallery in protest against the New Realist exhibit. In her review of the UMMA’s New Realist Supplement exhibition in the Michigan Daily, the graduate student Miriam Levin made similar distinctions between artistic sensibility and banality by claiming that the artists Jasper Johns, Jean Tinguely, Stephen Durkee and Robert Rauschenberg elevated their work from Pop to New Realist by applying meaning and judgement into their presentation of reality, instead of merely presenting a subject. (Levin 1963). Perhaps it was the “slick” representations of familiar objects that sold Pop Art to viewers in a way that New Realism could not; however, the success of Pop Art can be traced directly back to its influences in Nouveau Réalisme.

Pop

While the French Nouveaux Réalistes named themselves, the term Pop Art was only beginning to catch on and far from a cohesive artistic movement in 1963. Despite working in the same period of the 1950s and 1960s, many of the most quintessential “Pop” artists were unaware of one another at the time. That said, there are definite connections to be drawn between the artists whose work would later be considered representative of the movement. These artists eschewed the emphasis put on emotion, morality, and the individual by the abstract expressionists and even the Nouveaux Réalistes who came before them, while maintaining the same spirit of experimentation. Instead of turning inward, these artists sought inspiration from the external world of mass and popular media. Their work is often oversized and ironic and possesses a deadpan sense of humor.

One of the most characteristic features of Pop Art is its willingness to embrace what art critic Clement Greenberg once denounced as kitsch: “popular, commercial art and literature with their chromeotypes, magazine covers, illustrations, ads, slick and pulp fiction, comics, Tin Pan Alley music, tap dancing, Hollywood movies, etc” (Greenberg 1939). The United States in the postwar era was a nation of rampant consumerism, and these artists wanted their art to reflect the times in which they lived. This approach enraged many critics, who believed in a necessary distinction between high and low art. Artists and critics alike also lamented what they perceived as a lack of skill, as many works involved techniques such as screen printing or the recreation of everyday objects, which obscured the artist’s touch. On the other hand, those who were not members of the artistic elite often delighted in Pop Art. Pop Artists’ willingness to reference everyday objects in their work allowed common people a chance to engage with high art in a way the might not have been able to before. This concept even led some cultural elites to embrace a more democratic attitude. Art critic Leo Steinberg asked readers his widely-read 1963 essay “Contemporary Art and the Plight of its Public: “May we then drop this useless, mythical distinction between--on the one side--creative, forward looking individuals whom we call artists, and—on the other side--a sullen, anonymous uncomprehending mass, whom we call the public?” (Steinberg 1962)

Looking back on the wider art scene

Though Pop Art is now considered to be a defining art movement of the 1950s and 1960s, other artists in this period were experimenting in ways that are not represented in either of the exhibitions at the University. Artistic movements such as performance art embraced the ephemeral nature of art and offered new avenues for people to interact with it. “Happenings,” extremely temporary and informal avant-garde art events, cropped up around this time only to be gone almost immediately. In a certain sense, the fact that Pop and New Realist works were shown in galleries and museums was a more traditional approach that what was characteristic of the art scene at the time. Even so, the artists featured in the UMMA’s exhibit challenged established artistic conventions and reflected the cultural shifts that marked the end of the “American century”.

-Sarah Anne Kavaller and Ryan Lakin