Addressing Inner City Issues

SDS and the War on Poverty

The Port Huron Statement touched on multiple fronts, including the urban crisis and the problem of poverty. The SDS manifesto criticized “a national celebration of economic prosperity while poverty and deprivation remain an unbreakable way of life for millions in the ‘affluent society.’” Automation replaced workers with machines and facilitated the increase in unemployment. For SDS, achieving American democracy and expanding the civil rights movement to the North required a battle against poverty. The Port Huron statement blended separate issues into one common fight: “The fight against poverty, against slums, against the stalemated Congress, against McCarthyism, are all fights against the discrimination that is nearly endemic to all areas of American life.” In these ways, the Port Huron Statement anticipated SDS’s formation of the Economic Research and Action Program, otherwise known as ERAP. In his memoir, Tom Hayden wrote that ERAP “was a product of intense thinking about the intertwined issues of race and poverty and how to bring them to center stage in a nation consumed by the Cold War.”

SDS launched the ERAP initiative in the fall of 1963, four months before President Lyndon B. Johnson declared a national “War on Poverty” in his State of the Union address. In May 1964, Johnson introduced his vision of a liberal “Great Society” in a commencement address at the University of Michigan. The president proclaimed that “the Great Society rests on abundance and liberty for all. It demands an end to poverty and racial injustice, to which we are totally committed in our time.”

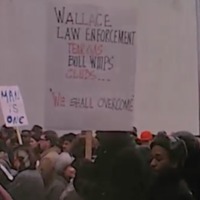

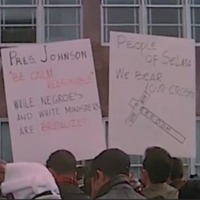

Anti-poverty activism built on the civil rights movement in the South, where Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee was working with local black communities to address racial and socioeconomic discrimination. SDS lacked this direct connection to communities outside the university and decided to apply these tactics to the urban North as well. While SDS members worked on ERAP projects on the ground, the escalation of the war in Vietnam undermined Johnson’s commitment to the Great Society. Todd Gitlin, the SDS president in 1963-1964, wrote that “his [Johnson’s] war also passed a death sentence on his Great Society. . . . Cold War liberalism was forced to choose between the two terms of its definition, and chose war.”

Intellectual Origins

The leaders of SDS set forth the philosophy behind the ERAP mission in the 1963 document “America and the New Era.” This document argued that American intellectuals should focus on forming solutions to problems “with regards to poverty, unemployment, social services, public planning, education, cultural life, and housing.” It highlighted how the Civil Rights Movement did not adequately address the links between poverty and racial discrimination. SDS planned to confront the issue head-on with a comprehensive program working with the poor to combat the oppression of poverty. Several years before the anti-war movement, ERAP represented participatory democracy in action.

Later in 1963, in a pamphlet called “A Interracial Movement of the Poor,” SDS members Tom Hayden and Carl Wittman refined how the change proposed in “America and the New Era” should be confronted. Carl Wittman worked with the NCAAP in Chester, Pennsylvania. There, black residents and students held demonstrations for fair employment and better housing. After his experiences in Chester, Wittman blamed the failure of the demonstrations on the exclusion of poor whites within the movement. One of the main points of the document explain that “demands which are specifically racial, do not achieve very much.” In addition to Wittman’s critiques, Hayden believed that the “old guard” of moderate liberalism lacked the fervor to inspire the students in the New Left. ERAP offered “improving our quality of work and making opportunities for radical life vocations.” Hayden pointed out that direct action could light the fire of radicalism for a new generation of activists.

History and Legacy of ERAP

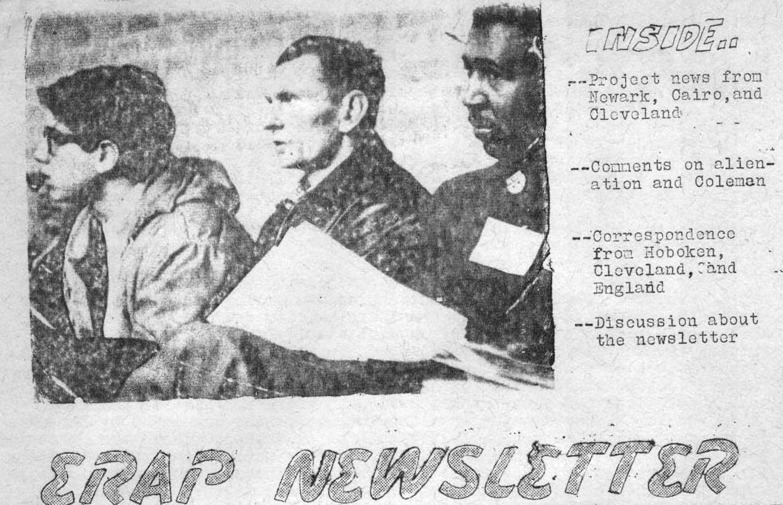

The Economic Research and Action Program began in September 1963. The United Automobile Workers initially funded ERAP through a grant. Recent UM graduates Tom Hayden and Sharon Jeffrey served on the executive committee, along with incoming SDS president Paul Potter. Through ERAP, the New Left sought not only to assist in local communities but to lend the poor a voice and create a biracial movement of the poor. The cities ERAP focused on included Chicago, Chester, Cleveland (where Potter and Jeffrey worked), Baltimore, Louisville, Newark (where Hayden and Carl Wittman worked), Philadelphia, and Trenton. Hayden, in a 2015 interview added that the “staff leadership were all our age and they had left campuses, they had been expelled from school, they were students and they were knocking on doors doing organizing.”

Sharon Jeffrey devoted the most attention of all SDS members to ERAP and one of the most active female members of SDS. She soon became the first full-time staff member of ERAP in Cleveland. (miller 185) Her Socialist politics, developed from her parents, left her unsatisfied with student organizations such as the Young Democrats until she met Al Haber, the first SDS president, when the organization remained under the LID umbrella. Al Haber represented what Jeffrey expected from a university: students guided by their human values working towards social reform. Sharon Jeffrey added that SDS “set an enormous amount of movement and change into action.”

During her time at University of Michigan, Jeffrey worked on a community center within the black community. This would influence her commitment to ERAP in the future. After her graduation from the University of Michigan, Jeffrey became an organizer for the Northern Student Movement in which white college students brought new political, social, and economic awareness to the poor communities in the northern states. Jeffrey desperately believed this was the missing piece in SDS activism. There had been little community action and ERAP served as the connection between politics and life issues, such as poverty. In a later interview, Jeffrey explained that ERAP created “an alternative for people, for students, to organize in a much broader context than just Civil Rights and just in the South.” ERAP allowed her to turn the theories of SDS into a program which organized the poor who were stripped of their political voice. While SDS searched to find out the meaning of participatory democracy, ERAP practiced what it preached.

Towards the end of the program in 1965, ERAP activists faced a moral dilemma: had the SDS members been imposing their New-Left values on the poor? Along with this, ERAP failed to confront the complexities of each community, and organizers became disillusioned by the tension between their lofty spirits and the harsh realities. ERAP’s positive legacies include the fact that many of the New Left organizers stayed committed to anti-poverty activism, even while the Vietnam War escalated. As an illustration of participatory democracy in action, ERAP represented “someplace to go when you left campus,” as Tom Hayden recalled in a 2015 interview.

The Vietnam War interrupted Hayden’s community organizing at the ERAP site in Newark. In the mid-1960s, Johnson’s escalation of the Vietnam War proved the final straw for SDS, and its attention shifted from anti-poverty activism to the anti-war effort.

Citations for this page (individual document citations are at the full document links).

Students for a Democratic Society, “The Port Huron Statement,” June 15, 1962.

Tom Hayden, Reunion: A Memoir (New York: Random house, 1988), 125.

Lyndon B. Johnson, “Remarks at University of Michigan,” May 22, 1964, Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States, 1964, Book I, pp 357-358.

The Great Society Project, “Examining the Impacts of President Johnson’s “Great Society”” (May 22, 2014), University of Michigan Economics Department, <https://www.lsa.umich.edu/vgn-ext-templating/v/index.jsp?vgnextoid=084fe634ae226410VgnVCM100000c2b1d38dRCRD&vgnextchannel=ac78ff2da82d0310VgnVCM10000055b1d38dRCRD&vgnextfmt=detail>.

Todd Gitlin, The Sixites: Years of Hope, Days of Rage (New York: Bentam Books, 1987), 178-179.

Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) Archives and Resources, “America and the New Era” (1963), Links to Resources from Students for a Democratic Society and Related Groups and Activities, <http://www.sds-1960s.org/documents.htm>.

Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) Archives and Resources, Tom Hayden and Carl Wittman, “An Interracial Movement of the Poor?” (1963), Links to Resources from Students for a Democratic Society and Related Groups and Activities, <http://www.sds-1960s.org/documents.htm>.

James Miller, Democracy in the Streets: From Port Huron to the Siege of Chicago, (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1994).

Interview of Tom Hayden by Chris Haughey, Obadiah Brown and Maria Buczkowski, March 29, 2015, Ann Arbor, MI.

Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) Archives and Resources, SDS Bulletin Volume 2 #10 (July 1964), Links to Resources from Students for a Democratic Society and Related Groups and Activities, <http://www.sds-1960s.org/SDS-Bulletin.htm>.

Bret Eynon “Interview of Sharon Jeffrey,” December 1980, Jeffrey, Sharon, Box 1, Contemporary History Project (The New Left in Ann Arbor, Mich.) transcripts of oral interviews 1978-1979, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) Archives and Resources, ERAP Newsletter (July 23, 1965), Links to Resources from Students for a Democratic Society and Related Groups and Activities, <http://www.sds-1960s.org/documents.htm>.

A New Insurgency: The Port Huron Statement in its Time and Ours, ERAP pamphlet cover (1964-1965), University of Michigan College of Literature, Science, and the Arts, <https://www.lsa.umich.edu/phs/resources/historicimages>.