The First U of M Teach-In (March 1965)

"Turning Away from Business as Usual"

As the U.S. became increasingly militarized in Vietnam, a select group of University of Michigan professors formed the Faculty Committee to Stop the War in Vietnam. Their goal was to organize a “work moratorium,” or a strike, in opposition of the ‘moral, political, and military consequences’ of the war and to get their colleagues as well as students involved. Later, Carl Oglesby, President of SDS, would refer to this "turning away from business as usual" as a "stroke of genius out their in Ann Arbor, Michigan."

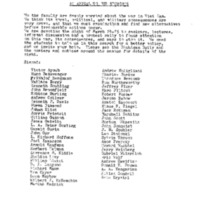

The fifty-eight professors, whose names appeared on, “An Appeal to Our Students”, faced backlash from the administration and the state government. They were forced to innovate new tactics instead of their initial idea of a “work moratorium.” As a result, the “teach-in” was formed, capturing national attention and gaining traction at other Universities. In a 2015 panel, “Teach-in +50: End the War on the Planet”, Professor Bill Gamson reflects on the switch from a “work moratorium” to a “teach-in”, “the plan to switch really kept that original notion that...this is not business as usual.” Gamson even indicated that the university administration became more cooperative when the switch to a teach-in occurred. For example, they allowed the professors to book rooms for the event.

Backlash

State Government

The professors faced criticism for their idea of a “work moratorium”. Many dissenters claimed professors were lazy and irresponsible claiming they wanted to miss their classes. In a 2015 interview with Professor William Gamson, a leader of the teach-in and professor in the University of Michigan’s Sociology Department, he laughs while he recalls, “I didn’t really reveal the fact that I didn’t have classes that day.” A Complaint Report was filed through the Michigan State Police against the teachers who wanted to protest United States policy in Vietnam War.

Preceding the weeks of the teach-in, correspondence between Governor Romney and several Michigan residents showed his disagreement with the faculty’s initial work moratorium. George Romney believed the “strike” would be the ‘worst type of example for professors to set for their students’ and therefore condemned the teach-in. Romney questioned if the faculty “truly represented the ‘conscience of our country’ when replying to a letter from Max Wender.”

Arnold Kaufman, a professor of Philosophy at the University of Michigan who helped organize the teach-in, was reprimanded by Governor Romney for his article in the Nation, “you are inviting anarchy in saying that you, or any other person or group, have the right to decide when an issue is important enough to halt the regular activity of a public institution.” Although the response occurred in August 1965, it echoed the feelings of discontent that Romney had towards the teach-in and the faculty that were involved in organizing it. Romney considered the teach-in to be a threat to the university as a public institution, and the issues that the faculty were garnering attention for were not worthy enough to stop classes.

U of M Faculty

Various University professors disagreed with faculty involvement in the anti-Vietnam War protests. In a letter addressed to Governor Romney from William H. Stubbins, a professor of Music at the University of Michigan, Stubbins shared the same views as Romney. As a member of the faculty for over twenty years, Stubbins thought that the opinion of a minority can cause great harm to the view of the University of Michigan as a whole and went on to call the teachers ‘fringe’ faculty.

Dissent Among the Organizers

Dissent grew among faculty organizers regarding the method of resistance. Some organizers, including Tom Mayer, believed that agreeing to a teach-in was a cop-out. Marshall Sahlins, professor of Anthropology at the University of Michigan and creator of the concept of a “teach-in”, reflects on the shift from a “work moratorium” to a “teach-in": “let’s prove that we were responsible, because we were being criticized as irresponsible...by teaching all night. Let’s teach "in" instead of teaching "out." And of course there was a Civil Rights Movement there was a sit-in and SNCC was doing it in the South.” The administration felt relieved by the faculty's decision and began to cooperate with the faculty organizers.

March 1965 Teach-in

From 8pm March 24th until 8 am March 25th, the first teach-in took place in Angell Hall Auditorium at the University of Michigan. Not only were University of Michigan faculty invited to speak, other faculty and activists across the country were asked to share their experiences and opinions. The point of this teach-in was to openly practice and encourage debate, one of the necessary characteristics of a democracy. Some of the prominent speakers included: William Gamson, Arthur Waskow, Anatol Rapoport, Michael Zweig (future chairman of Voice), Carl Ogelsby, Al Haber, Frithjof Bergmann, and J. Edgar Edwards. During the teach-in, two bomb threats occurred, causing panic and temporary displacement of the events. Professor Arnold Kaufman provided his own account of the events that occurred at the teach-in:

“the first American teach-in occurred at the University of Michigan on March 24. It was attended by about 3000 persons. The format consisted of the following: three major speeches...were followed by a question period lasting about an hour and a half. The schedule was disrupted by two bomb threats (the police cleared the halls once). At midnight, or thereabout, a protest rally was held outside. After that, at about 1 a.m., seminars, thirteen of them dealing with various aspects of the Vietnam crisis, assembled. These lasted until about 6 a.m., some uninterruptedly. After a bit of folks singing and a general meeting in the main auditorium, we reassembled in front of the library for a concluding protest. The statements-some 500-who still remained disbanded at 8 a.m. No one was excluded from either the audience or the seminars.” The Michigan Daily reported the two bomb threats, which were organized by a Pro Vietnam Group, displayed the mixed reactions that the students on campus had towards the teach-in. Robert Moore reported that “protesting groups picketed the teach-in, backing administration foreign policy… they marched around the midnight rally waving flags with ‘Drop the Bomb’.” Despite the disagreement on the teach-in, the demonstration carried on as it was planned. In a 2015 interview with William (Bill) Gamson, a leader and organizer of the teach-in, he described the night of the teach-in as “intense” and “explosive."

Teach-in Reactions and Responses

Varying opinions surfaced in support and against the teach-in. Michael Badamo wrote in a Michigan Daily article entitled, “The Viet Nam Protest: Some Chose Not To Talk...”, the pro-Vietnam War opinion was nowhere to be found at the teach-in. Instead, protesters in favor of the war, gathered in the diag with signs reading, “Better dead than Red”. Another columnist of the Michigan Daily, David Block, agreed, “the professors were concerned with having their position clearly presented; however, they should have realized that this could be effectively and democratically done only by enlisting pro and con speakers, thus providing an open forum for a free and unprejudiced discussion of the issue, not a subjective one-sided presentation”. In his own hand-written notes, Arnold Kaufman responds to concerns regarding why only dissenters of the war were invited to speak, “We felt justified in “inviting” only those who opposed American policy as main speakers on three grounds. First, we wanted not only to discuss, but to protest the enlargement of the Vietnam War. Second, there is much disagreement within our group. Some of us advocate withdrawal, some reject only the war’s enlargement and virtually every position bounded by these two points of view was represented. There was plenty to discuss and debate...Third, it is not as if the government of the United States is unable to find a way to place their position before the people”. Gamson agrees and further explains sentiment for the anti-war position, “...the other side, the anti-Communist, was being presented all of the time. This was an occasion where we were trying to develop the anti-war side of it...it’s not just presenting arguments on that...it was about looking at the various sorts of issues within it."

Faculty Impact on the Movement

The participation of faculty in anti-war activism is significant to the movement. As Frithjof Bergmann explained in 2015 at a “50th Anniversary Anti-War Teach-in” panel, the teach-in was the first time professors were political. The faculty found beneficial tactics for political engagement through the teach-in. Creating local and national consciousness about the Vietnam War led to progress within the movement. In a 2015 interview, Marshall Sahlins indicated, “I think a lot of the students first learned that their professors were people, that they actually had some kind of personal relation, and that they were passionate about something besides microbes or whatever they were teaching.”

Transition from Faculty to Students

Over the course of the anti-war movement, leadership shifted to the students from the initial faculty led teach-in. Throughout the course of the teach-in, one of the most salient characteristics of the movement was its fluidity. The teach-in was an organic entity, one that adjusted, as needed, to the conditions surrounding it. When faced with pressure from Governor Romney and the state legislature, the professors involved in the teach-in adapted their strategy, adhering to official policy by hosting the teach-in during the night and not disrupting the normal flow of classes. When faced with successive bomb threats, the assembled faculty and students simply paused, moving the events to another location on campus. Different factions existed within the organizing bodies of the anti-war movement leading to varied opinions on the appropriate future of the movement. The teach-in served as one of the first active stances, on college campus’, as growing dissatisfaction for the United States involvement in the Vietnam War increased.

Citations for this page (individual document citations are at the full document links).

“Confirmation for Teach-in,” March 24, 1965, Folder Teach-in March 1965(1), Box #4, Arnold Kaufman Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

Interview of William Gamson by Maria Buczkowski, Ann Arbor, Michigan, April 3, 2015.

“An Appeal to Our Students,” March, 24, 1965, Vietnam Teach-in Clips, Box #5, J. Edgar Edwards Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

“Handwritten notes about the teach-in, ” March 24-25, 1965, Folder Peace Movement Teach-ins (1), Box #4, Arnold Kaufman Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

“George Romney Letter to Arnold Kaufman,” August 9, 1965, Folder Correspondence 1965, Box #1, Arnold Kaufman Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

Redacted, Complaint to Michigan State Police, April 7, 1965, Zelda F. Gamson Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

Michael Becamo, “The Vietnam Protest: Some Chose Not to Talk,” The Michigan Daily, Date.

“Letter to Max Wender from George Romney,” March 23, 1965, University of Michigan RE: Vietnam, George Romney Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

“Letter to George Romney from William H. Stubbins,” Colleges, University of Michigan, 1965, George Romney Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

Interview of Marshall Sahlins by Obadiah Brown and Maria Buczkowski, Ann Arbor, Michigan, March 27th, 2015.