The Teach-In Goes National

From Michigan to Washington

The March 1965 teach-in at the University of Michigan inspired a wave of more than fifty similar teach-ins at universities around the nation and directly challenged the Johnson administration’s ability to shape public opinion about the War in Vietnam. At Columbia University, just two days after the UM event, professors held an all-night teach-in attended by 2,000 students. “The students of the universities are coming out of a long sleep,” an economics professor who spoke at the event declared, in reference to the common characterization of American youth as the “silent generation”. At many universities, antiwar faculty collaborated with New Left student activists through ad hoc committees that organized events to expose and condemn U.S. policy in Vietnam, a vivid example of participatory democracy in action. At UC-Berkeley, after an overflow crowd attended the initial UM-inspired teach-in, the Vietnam Day Committee organized a second outdoor event that drew 30,000 students. After the State Department declined an invitation to send a representative, the Vietnam Day Committee placed an empty chair on stage to mock the Johnson administration for being too cowardly to debate its foreign policy. Mario Savio, a leader of the Free Speech Movement, told the crowd that the liberals in the Johnson administration kept the true story of what was happening in Vietnam from the American people and sought to discredit the antiwar movement as irresponsible and naïve. “In what sense is decision-making in America democratic,” Savio asked, if “a very small group of people decide what the alternatives are?”

At the University of Michigan, the faculty group that organized the March teach-in immediately began planning ways to transfer the energy on college campuses to the national level. Along with student antiwar activists, these UM professors formed the Faculty-Student Committee to Stop the War in Vietnam. On April 6, 1965, Professors William Gamson and Eric Wolf circulated a letter on behalf of this committee to UM colleagues outlining the next steps: providing assistance to the teach-ins happening at other universities, sending a delegation (including Gamson) to D.C. to lobby Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, and supporting the SDS-led March on Washington scheduled for April 17. Most of all, the ad-hoc committee proposed a National Teach-In to be held in May 1965. In order to fund this initiative, the professors asked UM faculty to participate in a “pay-in” by donating a day’s salary.

After a follow-up public meeting in Angell Hall on campus, one community member in attendance filed a complaint with the Michigan State Police, reporting on Bill Gamson’s intentions to lobby administration officials in Washington and SDS President Todd Gitlin’s plans for the March on Washington later that month.

The Ann Arbor organizers initially invited McGeorge Bundy, the Special Assistant to the President for National Security Affairs and a leading architect of the Vietnam policy, to travel to UM to address the faculty. They believed that Bundy, a former professor of government and dean at Harvard University, would have difficulty resisting the pressure to spar with other academics in an intellectual arena. The letter emphasized the Johnson administration’s failure to explain what was happening in Vietnam to the American public and argued that the “government of a democracy must, we believe, clearly communicate its foreign policy” so that informed citizens could “evaluate, and if need be criticize, this policy.” After finalizing the plans for the National Teach-In, they extended a second invitation asking Bundy to be the main feature at the event in Washington. Bundy agreed to participate only after the IUC agreed to ensure a balance between critics and supporters of the administration policy throughout the event. Eric Wolf, a Professor of Anthropology at UM, welcomed the debate but sent a warning to his colleague in the White House: “Those of us in the academic community . . . do not intend to abdicate citizen responsibility because we are not in agreement with current official policy or strategy. This is a republic, not an autocracy and not a rubber-stamp democracy.”

Inter-University Committee for a Public Hearing on Vietnam

On April 17, 1965, teach-in leaders from six universities met in Ann Arbor to form the Inter-University Committee for a Public Hearing on Vietnam in order to mobilize support for the National Teach-In in Washington. In addition to the UM core, the founding members came from the University of Chicago, MIT, University of Wisconsin, Wayne State University, and Washington University in St. Louis. The IUC tapped into academic networks and quickly assembled a formidable group of co-sponsors among colleagues at institutions across the nation. In a reflection of their sense of urgency, the IUC described the looming “confrontation” between government policymakers and antiwar professors as “perhaps the most significant political gathering of American intellectuals since the Constitutional Convention.” Insisting on the need for “open public debate” about U.S. foreign policy, the IUC revealed the spirit of participatory democracy that animated the national teach-in movement. As seen in this fundraising appeal, the IUC quoted C. Wright Mills, the key philosopher of the New Left, to emphasize the “two things needed in a democracy: articulate and knowledgeable publics, and political leaders who if not men of reason are at least reasonable responsible to such knowledgeable publics.”

In April, a few weeks before the showdown, the Ann Arbor-based IUC set forth its philosophy of participatory democracy in a pamphlet titled “The Meaning of the National Teach-In.” While the immediate protest centered on U.S. policy in Vietnam, the “larger purpose” involved reviving the “process of discussion and debate without which democracy lacks significance.” In a sharp critique, the IUC pointed out that the teach-in movement came about because “many in our government tried to manipulate the American people into consensus about the war in Vietnam.” The faculty coalition also criticized administration officials for suggesting that dissent against U.S. foreign policy was “irresponsible and unpatriotic.” In particular, the IUC condemned the charge that such criticism encouraged the communist enemy as “subversive of meaningful commitment to democracy.” Instead, engaged citizens and experts outside of the government had a responsibility to speak out against escalation, including the bombing of North Vietnamese industrial and civilian targets and the possibility of a land war in South Vietnam. The national teach-in meant that the intellectuals on the campuses “will not be ignored. And we will not be silenced.”

On May 15, faculty participants from universities around the county participated in the National Teach-In on the Vietnam War. Five thousand people attended the event, many of them college-age, and the organizers also arranged for more than one hundred university campuses to participate via radio and telephone networks. The program promised an “exploration of policy alternatives” through “balanced discussion, confrontation and debate with the government.” In dramatic language, the IUC proclaimed the National Teach-In a “necessary extension of the intellectual’s responsibility as a teacher and seeker of truth. . . . We assert our duty, as intellectuals and as citizens, to question American policy. We assert our obligation, in a time of crisis, to bring before the nation and the world our doubts about the wisdom and morality of the American position, our fears that a hardened military policy may be leading the world to the brink of nuclear war.”

The Intellectuals vs. the Administration

After all the build-up, the National Teach-In on the Vietnam War began on a deflating note with the last-minute withdrawal of the White House’s sole representative, National Security Advisor McGeorge Bundy, ostensibly for an urgent trip to the Dominican Republic. In a public statement read at the start of the event, Bundy expressed regret for his inability to attend the debate and then sought to minimize the national teach-in’s impact while warning of the risks of open criticism of U.S. foreign policy. While Bundy praised the academic values of “fair and open discussion,” he also warned that public debate “can give encouragement to the adversaries of our country.” Bundy also asserted that the American people “know that those who are protesting are only a minority—indeed a small minority—of American teachers and students.” Then he concluded that the Johnson administration and the national teach-in movement each wanted the same outcome, but “we evidently differ on the choice of ways and means to peace.”

The National Teach-In succeeded in drawing a large crowd along with major media coverage and therefore focused public attention more than ever on the events in Vietnam. The New York Times published lengthy selections from many of the presentations, in the spirit of the informed discourse that the organizers sought. Moderator Ernest Nagel, a philosophy professor at Columbia, began by emphasizing that faculty and students alike had a particular responsibility to debate urgent matters “in a liberal democracy such as ours in which government policies require the assent of its citizens.” The main goal of the evening, Nagel reminded the audience, “is to contribute to the public enlightenment through responsible discussion,” but he also acknowledged the necessity of the intellectual tradition of “vigorous and informed opposition to those entrusted with political power.” Those in attendance heard a dense and passionate features well-known academics such as anthropologist Eric Wolf of the University of Michigan, political scientist Hans Morgenthau of the University of Chicago, and--on opposite sides--New Left historian William A. Williams of the University of Wisconsin and the liberal anticommunist historian Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., of Harvard. After these debates between the administration’s defenders and critics, break-out panels explored topics such as the domino and containment theories, the nature of counterinsurgency warfare, the history of Southeast Asia, and the morality of U.S. foreign policy.

On May 16, the day after the National Teach-In, the IUC leadership in Ann Arbor sent McGeorge Bundy a sharply worded telegram requesting “in the immediate future an alternative confrontation which will allow you to fulfill your commitment to us.” The IUC proposed a televised debate between Bundy and a panel of antiwar professors, with the hope that such a dialogue would lead the administration to reevaluate its escalation of the war. Richard Mann, a UM psychology professor and teach-in leader, followed up with a much less combative personal letter, acknowledging that the IUC had seemed to be “talking past you, not to you,” and recommending a second attempt at an “honest and respectful dialogue.” In a 2015 interview, Mann recalled his efforts to convince Bundy that the UM organizers sought to debate rather than ambush him, and his disbelief when Bundy once phoned him at home that it was really the White House on the line. The IUC finally did secure its “confrontation” with McGeorge Bundy, a network television debate in late June between the National Security Advisor and several IUC members, including Hans Morgenthau of the University of Chicago. Bundy argued the administration line that the U.S. had to stay in South Vietnam in order to stop the spread of communism throughout Asia, while one of his critics warned with prescience that the only way to win the war would be to “virtually annihilate” the Vietnamese people.

UM faculty and students involved with the Inter-University Committee organized one final event during 1965, a September conference on “Alternative Perspectives on Vietnam.” Planning took place with a sense of alarm, because despite the teach-in movement and the SDS March on Washington, the Johnson administration remained committed to the military build-up and the Cold War doctrine of containment. The conference’s statement of philosophy explained that the teach-ins had raised public awareness but failed to offer a viable path out of Vietnam, which brought an urgent need to transcend “the assumptions of the Cold War” entirely. Religious leaders in the Ann Arbor area played a major role in planning the conference, and the speakers included many international scholars and pacifist activists. Like SDS’s call for participatory democracy, the agenda focused on the possibility of an alternative moral system for the conduct of foreign policy: “what values should be pursued in Vietnam, in what ways current American policy frustrates and violates these values, and what alternative policies would be more consistent with the achievement of these values.”

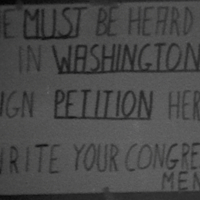

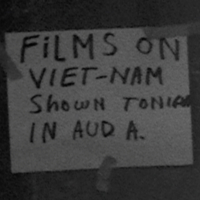

The scenes above are from the "Alternative Perspectives on Vietnam" international conference, held September 1965, the last major event organized by the Ann Arbor-based Inter-University Committee for a Public Hearing on Vietnam.

Conference participant Christopher Lasch, a New Left intellectual who would soon become a prominent historian of American culture, left with the belief that “the theory of American benevolence must be confronted with the theory of the dirty war” in Vietnam. It was time, Lasch declared, for the anti-Vietnam War movement to offer a fundamental reassessment of U.S. foreign policy and to embrace an anti-Cold War philosophy “in which the whole myth of American benevolence would be tested against the theory that Americans are not exempt from the corrupting influence of great power.” With this critique, Lasch also captured the increasingly militant stance of the leaders of Students for a Democratic Society, whose strategies of confrontation had moved beyond teach-ins to mass marches and direct resistance against the war.

Citations for this page (individual document citations are at the full document links).

McCandlish Phillips, “Now the Teach-In: U.S. Policy Criticized All Night,” New York Times, March 27, 1965.

W. J. Rorabaugh, Berkeley at War: The 1960s (New York: Oxford University Press, 1989), 91-92.

Mario Savio, “Speech at Vietnam Day Teach-In,” May 21, 1965, Free Speech Movement Archives, <http://www.fsm-a.org/stacks/mario/savio_vietnamday.html>.

Max Frankel, “Vietnam Debate Heard on 100 Campuses,” New York Times, May 16, 1965.

“Excerpts from National Teach-In on Vietnam,” New York Times, May 17, 1965.

Interview of Richard Mann by Matt Lassiter and Obadiah Brown, Ann Arbor, Michigan, April 3, 2015.

Christopher Lasch, “New Curriculum for Teach-Ins,” The Nation (October 18, 1965), 239-241.

National Teach-In documents from Box 1, Richard D. Mann Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan; Box 5, J. Edgar Edwards Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.