United Students Against Sweatshops

Union Summer

With the election of John Sweeney as president of the national AFL-CIO in 1995, labor unions began a national effort to reach out to college students. In 1996, the AFL-CIO launched a program entitled “Union Summer,” inspired by the Civil Rights Movement’s Freedom Summer of 1964, that placed students in internships with unions across the country. The program persisted for a few years, and many of the founding members of SOLE took part in Union Summer around the country during or prior to the summer of 1998. Peter Romer-Friedman, a founding member of SOLE, participated in Union Summer in New Orleans in the summer of 1998 working to unionize hotel employees. Romer-Friedman remembers the types of day-to-day activities the New Orleans cohort participated in: "Basically what we did was we door knocked to meet not just workers but anyone in the city to get them to support the idea of labor peace in New Orleans... And we also did meetings with workers who were part of active organizing campaigns... so we got to see first hand what it was like to be part of a union organizing campaign." Rachel Edelman, another SOLE founder also participated in the program in Denver, remembers the personal impact of Union Summer, “In retrospect, I am extremely grateful for the internship - I don’t think I’d be doing any of the work that I’ve done since if I hadn’t been introduced through Union Summer.”

The Beginning of Anti-Sweatshop Campus Activism

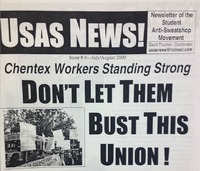

United Students Against Sweatshops (USAS), the major student sweatshop group of the late 1990s and early 2000s, directly emerged from Union Summer. The Union of Needletrades, Industrial and Textile Workers (UNITE), based in New York City, employed several of the Union Summer students, including Lee Palmer, a SOLE founder, and a rising junior at Duke University, Tico Almeida. These students, working together to alleviate labor conditions domestically, began to discuss ways in which they could extend this work to their college campuses, and were encouraged by their supervisor, Ginny Coughlin. With the sweatshop issue dominating the national media at the time, the students quickly seized on the idea of reforming apparel production for their own universities. Almeida and others’ began to outline a national organization that would provide coordination and information for the campus groups that had begun to emerge on the sweatshop issue. This group became United Students Against Sweatshops (USAS) in the summer of 1998. USAS chapters or affiliates sprang up at campuses across the country--by 2000 USAS had chapters at more than 200 schools--facilitated by the new email listserv and website technologies of the late 1990s. Notable USAS chapters appeared at universities with major athletic apparel contracts, like Wisconsin, Oregon, and Iowa, but also at smaller, private schools like the University of Pennsylvania, Macalester College, and Brown University. The range of campuses with USAS branches--small and large, traditionally activist and traditionally conservative--indicate the broad appeal of anti-sweatshop work as students began to recognize their clothing decisions as collusion in labor abuses. USAS successfully leveraged this into a realization that students, and the universities that represented them, had enormous power and responsibility to combat exploitative working conditions.

Simultaneous with the foundation of USAS, student sweatshop activists traveled to Union Summer locations urging students to bring the sweatshop issue back to their campuses and establish their own USAS affiliate. The type of campus organizations they had in mind would follow the Duke example from 1997 where the first campus anti-sweatshop actions took place. Duke was an early leader in the anti-sweatshop movement thanks to the work of Almeida in establishing the Duke Students Against Sweatshops (SAS) group, one of the first of its kind in the country. In 1997, these student activists sent a letter to Nan Keohane, then president of Duke, urging revisions to the university’s Code of Conduct for the production of their licensed apparel. The letter led to months of negotiations with university administrators, but SAS became increasingly worried that the university would not adopt the code they had proposed. In January of 1999, the Duke students staged the first campus anti-sweatshop sit-in to pressure the administration on the Code of Conduct, eventually resulting in the adoption of SAS’s version after a 31-hour-long occupation. The demands and tactics of the Duke Students Against Sweatshops would be reproduced at universities across the country--first at Georgetown, then at Wisconsin, and next at Michigan, where students occupied the presidents office for 51 hours.

As the student anti-sweatshop work became a movement, comparisons with earlier campus activism inevitably surfaced. In particular, USAS was often compared to Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), the student-led anti-Vietnam war organization of the 1960s. Both organizations originated at elite or flagship state schools and members tended to come from white, leftist families. Both movements shared a “democratic impulse” that relied on direct action tactics, most notably sit-ins, to promote their cause. SDS and USAS also used the tactic of pressuring their universities to regulate companies--SDS targeted chemical suppliers like Dow, and USAS targeted apparel manufacturers like Nike. While SDS and USAS do differ in several ways--USAS has a much closer relationship with American labor than SDS did, and has benefitted from the new technologies of organizing (email, cell phones, the internet)--their basic ideologies vary little. Robert Ross, a sociologist and former SDS member, describes the how leaders of both movements developed increasingly socialist, anti-capitalist sentiments, but understood the risk of alienation should they center the movements around these ideas. Ross notes that “Emerging from the Cold War, SDS leaders knew that mainstream Americans could not hear the word socialism,” and that USAS leaders do not “think they could communicate this vision [socialism] successfully to their peers or to other Americans.” Student activists of both eras made conscious efforts to distance themselves from radical ideology publicly, while often supporting it privately. When Students Organizing for Labor and Economic Equality (SOLE) formed on Michigan’s campus, this was a strategy they constantly employed, as Jackie Bray describes in the context of the 2003 GEO strike at below.

Seattle WTO Protests

The campus anti-sweatshop movement arose within a national and global movement against corporate greed and globalization. In November of 1999, Seattle hosted the World Trade Organization for a round of trade talks involving representatives from 135 nations in what would become an iconic symbol of the anti-globalization movement. The World Trade Organization, founded in 1995, seeks to promote free trade by reducing trade barriers between nations, and can do so by vetoing national laws that threaten imports--including food safety standards, labor protections, and environmental standards. As Seattle prepared for the meeting, activists from a broad range of backgrounds and locations converged on the city to protest the organization. Most prominent among the protesters were union members and environmentalists. Some activists wore turtle costumes to highlight the WTO’s overturning of protections for endangered sea animals, leading many to describe the protesters as the “teamsters and turtles.” Students also constituted a sizeable portion of the protesters, including Andrew Cornell, a SOLE founder, who felt compelled to participate in the protests after hearing a talk by anti-globalization activist Kevin Danaher.

During the meeting, protesters filled the streets and blocked delegates from entering the convention center, leading to the cancellation of the opening ceremony and other scheduled events. The protests were largely peaceful and nonviolent, but a small group did smash car and shop windows. The Seattle police responded with tear gas, pepper spray, rubber pellets and dozens of arrests. After the first day of protests the governor of Washington called in the National Guard. The Wall Street Journal describes the situation from the Clinton administration’s point of view: “To placate underdeveloped countries, the U.S. must open its market to textile imports, ease up on its strict enforcement of antidumping rules and back off from its demands that the WTO start looking at labor rights. But to placate the protesters...the U.S. needs to do just the opposite.” The Seattle activists largely viewed the conflicts in Seattle as a success--in the short-term for halting WTO negotiations in Seattle, but in the long-term for introducing the American public to the drawbacks of free trade and sparking a global coalition to combat corporate globalization. The “Battle for Seattle” quickly became a national symbol of the fight against globalization and the challenge to the bipartisan consensus on free trade, of which the student sweatshop movement was only one part.

Citations

Peter Romer-Friedman, Skype interview, March 27, 2015.

Rachel Edelman, email interview, April 16, 2015.

Lee Palmer, email interview, April 16, 2015.

Swarthmore College, "Global Nonviolent Student Activism Database: Duke students campaign against sweatshops 1997-1999," http://nvdatabase.swarthmore.edu/content/duke-students-campaign-against-sweatshops-1997-1999.

Duke Students Against Sweatshops, "Previous Campaigns and Victories!" https://web.duke.edu/usas/previouscampaigns.html.

Liza Featherstone and USAS, Students against Sweatshops, (Verso: New York, 2002).

Liza Featherstone, "The New Student Movement," The Nation, May 15, 2000.

Matt Lassiter, Globalization Lecture

Andrew Cornell, email interview, April 12, 2015.

Helene Cooper, "Waves of Protest Disrupt WTO Meeting" The Wall Street Journal, December 1, 1999.