SOLE Sits-In for Workers Rights Consortium

In the fall of 1999, SOLE students drafted an eleven-page proposal to the President’s Advisory Committee on Labor Standards and Human Rights urging its members to recommend WRC membership to President Bollinger. The Committee was split on the issue, with many members voicing concerns about the ambiguities of the WRC, which had not even held its inaugural meeting yet. In particular, committee members worried about the adversarial stance the Consortium took towards licensees and its reliance on complaint-based investigation. As a result of these doubts, the Committee repeatedly postponed voting on SOLE’s proposal. Frustrated with the Committee’s inaction, SOLE stormed a forum hosted by the Committee on January 18, 2000 calling for a vote on the WRC proposal. When it became clear the Committee would not vote, the two SOLE members of the Committee resigned and the organization demanded Bollinger make a decision on the WRC by February 2nd. As the deadline neared, SOLE began planning a protest in case Bollinger refused to join the WRC.

As SOLE was planning its next action, students at the University of Pennsylvania were embroiled in their own fight for membership in the WRC. Unlike the University of Michigan, UPenn had joined the FLA and its branch of USAS, Penn Students Against Sweatshops (PSAS), were petitioning the university not only to join the WRC, but to drop their association with the FLA as well. On February 7th, PSAS began a nine-day occupation of the university president’s office that resulted in the school leaving the FLA and moving up the deadline for a decision on the WRC. This compromise was hailed by USAS as a major step in the right direction.

SOLE Dean's Office Sit-In

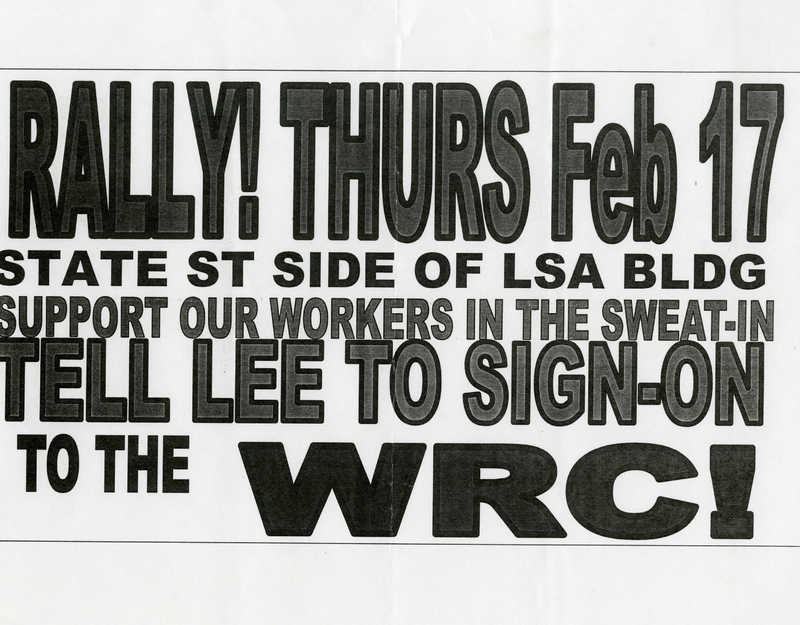

SOLE eventually extended the February 2nd deadline by a week, as Bollinger had to leave town unexpectedly. The extension did not help SOLE. Bollinger announced he would not endorse the WRC on February 9th, following a similar announcement from the University of Wisconsin Chancellor, David Ward, earlier that week. Inspired by the UPenn sit-in and in coordination with students at the University of Wisconsin, SOLE staged a sit-in in the College of Literature, Science, and the Arts (LSA) Dean’s office beginning on Wednesday, February 16th. Rather than simply occupying the building, as they had done the previous year in Bollinger’s office, SOLE students set up a mock sweatshop in the Dean’s office--making t-shirts and playing recordings of textile factory sound effects. The students also livestreamed the sit-in online (possibly the first sit-in to ever do so) and listed the Dean’s office for sale on eBay; the post’s description read: “University of Michigan Students Seek buyer for Dean’s office...The students are making U-M apparel in their mock sweatshop and they will not leave until President Lee Bollinger commits to ending the real UM sweatshops or UNTIL THEY SELL IT ON EBAY. SOLE, the student group taking over the office, is asking $3.60 for the office because sweatshop workers work for absurdly low wages, and we’re selling like absurd students.” eBay removed the post, but not before it garnered 20 bids up to $5,200.

President Bollinger met with the students quickly after the start of the sit-in, but the meeting only reinforced SOLE’s resolve. Bollinger told the students he needed more time to consider their proposal and the WRC, even admitting that he had not read the WRC policy himself. Bollinger’s timely response to SOLE stood in sharp contrast to the ongoing Michigamua protests and occupation of the Union tower, which was entering its tenth day. As the SOLE sit-in continued, Bollinger began receiving letters from unions around the country encouraging him to join the WRC, a campaign that continued even after he announced Michigan’s conditional membership. Under this mounting internal and external pressure, Bollinger began to work with the administrations of the University of Wisconsin and Indiana University to work out a solution.

On Friday, February 18th, Bollinger announced that the university would join the WRC, along with Wisconsin and Indiana, on a conditional basis. While Bollinger’s announcement ended the SOLE sit-in, students remained skeptical of the vague language of the arrangement. In a March 31st letter to Maria Roeper, the interim director of the WRC, Bollinger called the draft charter a “good starting point” and a “promising foundation,” but was clear about the advisory committee’s reservations regarding “monitoring, governance, and organizational viability.” However, much of campus saw this as a victory. The Michigan Daily applauded SOLE, running an editorial that praised SOLE for “providi[ing] decisive evidence that student activism can lead to positive change on crucial issues.” At the University of Wisconsin, student protesters were not satisfied with this arrangement and continued their occupation, which quickly escalated and resulted in mass arrests.

University of Wisconsin Sit-In and Implications for SOLE

Wisconsin activists coordinated with SOLE students to stage their sit-ins at the same time, but their experience differed widely. The University of Wisconsin protest provides a stark contrast to the Michigan sit-in and highlights Bollinger’s strategy when dealing with student protesters. On Wednesday, February 16, seven UW students entered the chancellor’s office. As they talked with a Vice Chancellor and Associate Dean, a hundred more student activists marched towards the building, but before they could reach the office university police locked and guarded the doors--leaving the original seven students inside. Inside the office, the students locked themselves together with bicycle locks and would have to leave the office permanently should they want to use the bathroom or eat. Outside the office, protesters pounded on the door, slipped things under it, and even tried to take it off its hinges. The university police responded by spraying the students with pepper spray and one student retaliated by discharging a fire extinguisher into the hallway.

The environment calmed after Chancellor David Ward ordered the office doors opened, but the protesting students were not satisfied by Ward’s announcement that night that the university would withdraw from the FLA, nor were they satisfied by the joint announcement on the 18th that they would join the WRC on a provisional basis. In response to Ward’s acceptance of the WRC, the students issued new demands, requiring an unconditional commitment to a five-year membership. University administrators were unwilling to consider this demand and so, even as their Michigan counterparts ended their sit-in, UW students continued. On Sunday, February 20th university police ordered the students to leave the building and when they did not, Ward authorized the police to remove and arrest the roughly fifty remaining students. Most were arrested on the charge of disorderly conduct, but several were additionally charged with resisting arrest, and one with underage drinking. SOLE students wrote to Bollinger, encouraging him to use his relationship with Ward to to push for “meaningful discussion” with the UW student activists, but whether or not Bollinger took that advice, conditions in Madison changed little. In an extended email to fellow Big Ten university presidents, including Bollinger, Ward explained that the students “have turned this debate into a confrontation over how this university be administered. They simply do not have that right.”

The Wisconsin protest differed from the Michigan one in several critical ways. First, the protesters themselves show differing understandings of civil disobedience. While the SOLE students were certainly disruptive to the functioning of the dean’s office, they were not destructive--no doors were battered, no fire extinguishers discharged, and no reports of alcohol consumption. SOLE activists also recognized when their battles were won--issuing clear demands and accepting their fulfillment. But the administrations they were dealing with also differed vastly. Whereas Bollinger met with the students immediately and often, Ward sent lesser administrators to meet with the students and left campus for a business trip as the sit-in continued. Bollinger may not have been enthusiastic about the WRC, but he realized that meeting with the students and dealing with the situation calmly would prevent bad press that would only serve to galvanize SOLE. In the Daily’s editorial congratulating SOLE, they also acknowledge Bollinger’s role in the success, pointing out that “while he may think it wise to take it slow with the WRC, he certainly does not seem to want to discourage students from voicing their opinions.”

Citations

President’s Advisory Committee on Labor Standards and Human Rights, Final Report, May 2000

Jon Fish, “Bollinger Holds off on WRC,” The Michigan Daily, Feb 10, 2000.

Jon Fish, “SOLE occupies forum, resigns from committee,” The Michigan Daily, Jan 19, 2000.

Jon Fish, “U. Penn abandons FLA,” The Michigan Daily, Feb 16, 2000.

David Enders, “Dean’s office listed on auction site,” The Michigan Daily, Feb 18, 2000.

Jon Fish, “Sweatshop protests draw attention: SOLE meets with Bollinger,” The Michigan Daily, Feb 18, 2000.

Interview with Scott Trudeau, email, April 9, 2015.

Aaron Nathans, “Push comes to shove,” The Capital Times, February 17, 2000.

David Ward to University Presidents, February 21, 2000, UM Office of the President

Aaron Nathans, “Protesters gear for more,” The Capital Times, Feb 21, 2000.

Michigan Daily Editorial Board, “Congratulations, SOLE: Group’s success shows value of activism,” The Michigan Daily, Feb 21, 2000

SOLE to President Bollinger, Feb 21, 2000 UM Office of the President.