Antiwar in War: The Battle Against Conscription

In July of 1917, Ellwood B. Moore, student at the Ann Arbor High School, member of the I.W.W. and prospective student at the University, was sent to the Detroit House of Corrections for refusing to register for the selective draft on June 5. A month earlier, Ellwood had written a letter to the Daily Times-News from his cell at the Washtenaw County Jail. Though the paper would not publish the letter, Agnes Inglis—a close friend and, presumably, mentor of his—and others passed it out to all those entering the Ann Arbor High School for the graduating ceremony, in which Ellwood would have received his diploma had he been a free man. “If not the most brilliant scholar he was the most brilliant the Ann Arbor High School ever had,” Inglis recalled in her "reminiscences". [1]

For larger image, click here

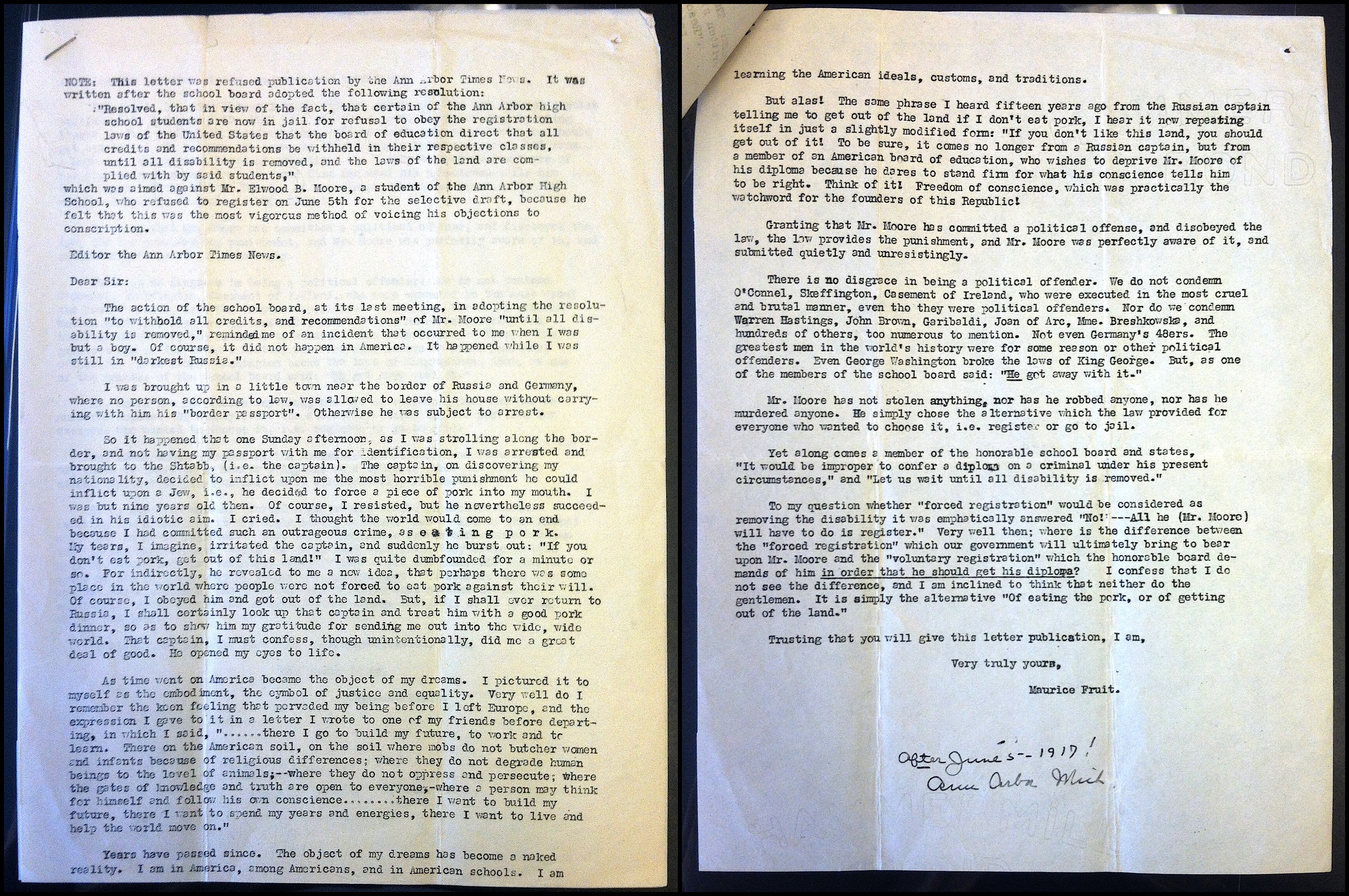

In response to his actions, the Ann Arbor school board refused to issue Ellwood his diploma, though his credits were in order and he had achieved high marks across the board. Until “the laws of the land are complied with,” the official resolution read, “all credits and recommendations” were to be withheld. Max Frucht, a second Ann Arbor conscientious objector, wrote a second letter to the Daily Times-News, and, yet again, the letter was refused publication. In it, Frucht recalled an episode from his childhood in Russia that illustrated how the authorities there treated Jews. The treatment of the minority opinion in wartime America, he suggested, did not differ much. He continued:

There is no disgrace in being a political offender…The greatest men in the world’s history were for some reason or other political offenders. Even George Washington broke the laws of King George. But, as one of the members of the school board said: “He got away with it.” [2]

For larger image, click here

Ellwood B. Moore and Max Frucht received at least a moment of renown for their actions. Both were mentioned in the July 1917 Volume of the International Socialist Review, and Ellwood’s letter was published in the July 1917 Friends’ Intelligencer, a Philadelphia-based Quaker newsletter. Frucht’s letter was published in a January 1918 Mother Earth bulletin [3]. Decades later, Emma Goldman remembered both Frucht and Moore when writing her autobiography, Living My Life. She mentions their names among such renowned conscientious objectors as Roger Baldwin and Philip Grosser [4].

Notes

Please click images for full descriptions and citations

[1] Subject Vertical Files ("Moore, Ellwood B." and "Pacifism--World War I"). Joseph A. Labadie Collection, University of Michigan Library.

[2] Subject Vertical Files ("Moore, Ellwood B."). Joseph A. Labadie Collection, University of Michigan.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Both Max Frucht and Ellwood B. Moore’s names are spelled differently in different sources. The International Socialist Review refers to a Max Frocht, while Goldman spells the surname “Frucht.” “Ellwood” is written in various sources as “Elwood,” although judging by frequency it appears that the former spelling is correct.