Radicalism After the War

Excerpt from pamphlet released by the Friends of Conscientious Objectors. For full pamphlet, click here

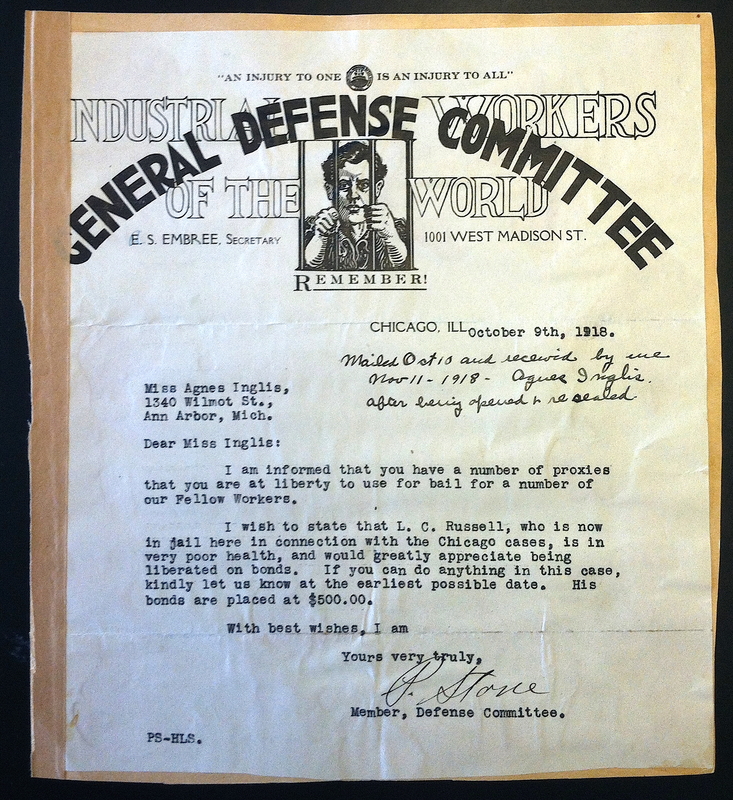

The banishment of her comrade, friend, and beneficiary did not spell the end of Agnes Inglis’ wartime experience as an antiwar activist. The 1918-1919 Red Scare, produced by a toxic combination of wartime anti-German hysteria and the international impact of the Russian Revolution, hit the Detroit radical community hard. Inglis worked hard into the 1920’s to support the rapidly crumbling IWW, protest the continued incarceration of conscientious objectors and other political prisoners, and militate for their release. Her efforts cost her her family fortune. By the mid-1920’s, she had discovered the Labadie Collection at the University of Michigan Library, a scholarly project to which she would devote practically the entire remainder of her life.

To read the article An Appeal to the Nation's Courage, published in The Detroit News at Inglis' request, click here

Ann Arbor and Detroit radicals, witnessing the rapid and devastating dismantling of their lives’ work proceeding around them, had one consolation: the hope and promise brought to the international radical movement by the 1918 October Revolution. Ironically, this very event spelled doom for the American Radical Movement, as it was the perceived threat of an invasion of Bolshevik ideology that spurred the Palmer Raids. Yet in November of 1918, events transpiring in Russia were, to Inglis and others, an isolated outpost of hope in a world of censorship and suppression. Recalling a meeting of radicals in Detroit, Inglis recalls:

McCallister Hall was packed the Sunday afternoon of November 24, 1918. The spirit of the audience was all astir. We were living, then, in a spirit of increasing repression. The Russian Revolution was the break in this deadening repression. And at this meeting the spirit of revolt against this repression was very illuminating…For my own part I was astonished. I had not realized the immense possibility for revolutionary spirit in America. It was for me a curtain lifted showing a developed solidarity of revolt and purpose I had not guessed at before, in regard to the American people. [1]

Click here for original image

Inglis’ predictions of newfound solidarity among and impending victories for radical Americans after the war were never realized: instead, the experience of World War I irreparably altered the conditions of the American radical political movement. The SPA and IWW emerged decimated and broken into irreconcilable factions; new organizations, such as the Communist Party and a heavily conservative AFL, emerged out of their fragments. The Palmer Raids and the hysteria that fed the 1919-1920 Red Scare kicked off the 1920’s in the vein of anti-radical, anti-union conservatism that would characterize the decade. Obviously, radical politics in the United States did not die with Jo Labadie and Gene Debs. But radicals’ prewar goals and expectations, hopelessly idealistic by today’s standards, were never allowed to materialize. Socialists’ pragmatic, compromising attempts to gain a firm foothold within the American electoral system, anarchists’ predictions of imminent revolution, syndicalists’ dream of union-controlled industry—all were fundamentally disrupted by political and social conditions altered by war. Inglis writes:

Throughout World War I, the University of Michigan campus was caught up in the same frenzy of hyperpatriotism that possessed most of the nation. What little radical antiwar activity occurred was confined to a few ardent individuals concentrated at 1340 Wilmot St., crowded upstairs in Woodman Hall, and kept behind bars at the Washtenaw County Jail. It appears that, in many cases, the young minds of the University and the workers in the town remained open to critiques of war, government and militarism even after Wilson’s proclamation of war. Yet their questions, and the firm and decided voices they might have listened to, were suppressed by the deafening majority who wrote the Daily Times-News, held the keys to the lecture halls, and maintained a trenchant and uncompromising control over the vehicles of public sentiment.

Emma Goldman and Agnes Inglis met once more, when, in March of 1934, the former returned to Ann Arbor to access materials at the Labadie Collection for her autobiography. For Inglis, Goldman’s visit was a sentimental and joyful occasion. She writes:

Notes

Please click images for full descriptions and citations

[1] Agnes Inglis Papers, Box 27, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.