Military Experiences

The events of the past don’t change, but the ways in which historians think about and understand them certainly do; World War I is no exception. Since the armistice in 1918, scholars have written the history of the war several different ways, and each reinterpretation has offered a chance to examine different perspectives on the conflict. What began as an academic attempt to determine fault in the immediate aftermath of the war gradually gave way to an exploration of its causes. The national and ethnic biases inherent in those methods made them impractical and ineffective modes of study, and by the middle of the twentieth century the historical focus had landed squarely on the everyday people of the war. For a conflict that drew every corner of the globe into the fold, the history of World War I is surprisingly personal. The story no longer belongs to its kings and diplomats, or even to its generals. Rather, those four years of destruction, decay, and death are best understood through the eyes of the ordinary men who died in the war as they likely would have lived in peace: deeply anonymous and undeniably human. This shift in academic thought trickled into the public sphere and has continued to fuel nearly every film, novel, and documentary about the war since: the World War I of A Farewell to Arms, Blackadder, and All Quiet on the Western Front is the everyman’s war just as the history of the conflict has become the everyman’s story. In this intellectual and cultural shift, the wartime experiences of the individual have been fairly well covered, the everyday lives and events of the war thoroughly tread and retread, and the diaries and photographs reprinted endlessly. The next shift in our understanding of the war is away from this rewriting of personal experience alone and towards an exploration of deeper meanings about the individual’s connection to the world beyond -- in this case, to the University of Michigan.

The centrality of the individual in war has lent a counterintuitive namelessness to its subjects, but for the sons and daughters of the University of Michigan who were involved in the war, anonymity was never a likely fate. Their names were writ large across the honor rolls of the Michigan Alumnus and many of their papers reside in the school’s archives at the Bentley Historical Library. They were current students or recent graduates of the university who traded dorm rooms for barracks, pulled from their studies and jobs to fight a distant war. The letters they sent home and the journals they kept tell fascinating stories of young men and women dropped into a harrowing world, but giving their voices a stage is only a part of the project here. All of them were connected to the same school, the same campus, the same fight song and colors. Their experiences are valuable elements of the historical record, but their connections -- in particular, to Michigan -- are even more so.

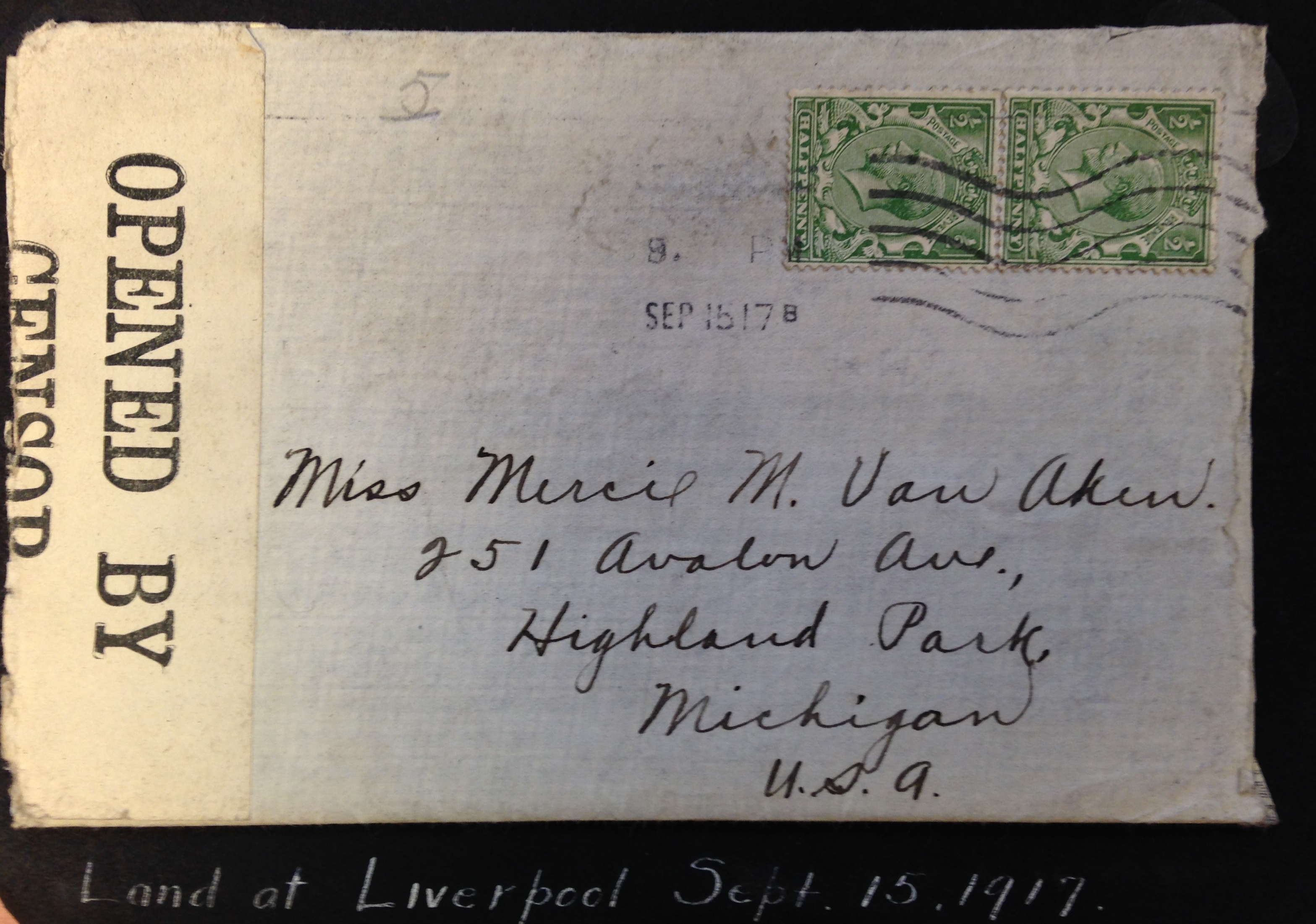

The arc of this exhibit, titled Military Experiences, is chronological, but the focus is on the themes that crop up along the way. Beginning with the tranquility of Ann Arbor before America’s entrance into the war, extending across an ocean to the trenches and hospitals of the Western Front, and returning to an unfamiliar campus transformed by militarism, many of the same powerful ideas weave in and out across the timeline. For soldiers who returned from Europe, the sheer inhumanity of what they had seen eluded words; to them, it was impossible for others to understand the war without having lived it themselves. This apparent incommunicability guides how we understand their stories, visible in the censorship that shaped their letters from the front and the memoirs they wrote after the facts and memories of the war had simmered for years.

Writing the history of such an enormous conflict as World War I through the eyes of a select few is a tricky business. Part of that stems from the small sample size, but most of the issue comes from the sources at hand: the censorship of the war continues to affect how we understand it, in more ways than one. Many of the letters home that remain are pockmarked with the mark of the government censors, who scanned every piece of mail to make sure military secrets stayed private. The sporadic patches of black ink clearly delineate the bounds of what soldiers were allowed to write; what they chose to write and what they chose to leave out, however, remains a grey area. World War I produced military horrors the world had never seen before, as tanks, airplanes, and chemical weaponry constantly revised the limits of battle. Torn between expressing their fears and reassuring their families, soldiers rarely included the whole of their military experience in letters home. This self-censorship limits what we can know about certain events of the war, but examining these gaps in knowledge in their own right provides an opening into understanding how soldiers perceived their situation and their relation to it.

Another notable lens for the history of World War I is that of gender, as men and women experienced the war differently. In a sense, writing about women in the war is similar to trying to fill in the gaps across the historical record -- their contributions in Europe were undeniable, but their narratives and roles have often been overlooked or marginalized. Of the letters that have been handed down and preserved, most are from the gunmen, the officers, and the sailors -- in a word, from the men. Far fewer are the records of the nurses, the tailors, or even the spies, but their experiences deserve the same attention to complete the picture of wartime experience. The women of the University of Michigan were well represented in WWI, and examining how their stories compare to traditional narratives of gender offers a valuable chance to peek into the machinery of history and memory. However, the changes in gender roles that emerged during the war hardly only affected women. American men entered the conflict with a firmly entrenched sense of their own masculinity, derived in large part from the legends of the Civil War.

Many of the ideological fault lines that split the experiences of men and women across the Atlantic were similarly divisive in Ann Arbor. Attitudes and approaches to the conflict varied widely at the time, and many of those same disagreements have persisted through memory into historical debates. Issues of censorship, gender, preparedness, memory -- all of these were truly international themes, reaching not only across the Diag, but across the globe.

Please click images for full descriptions and citations