Writing and Memory

It's easy to get lost in the content of letters and diaries from the front. Many of the soldiers believed that their experiences were wholly incommunicable and that understanding the war would be impossible for people who didn't experience it firsthand, but poring over their century-old writings today bridges the gap more than they might have thought. The stories found in the archives are incredible; even beyond the usual litany of horrors that accompanied life on the front, the details of the sources bring a reader closer to an understanding of the time, the place, and the experience. The accounts are involving enough and fascinating enough to stand on their own merit. It's easy to get lost among the rats, the mud, and the constant shriek of shells overhead.

And yet, for all the obvious story and narrative, there's an undercurrent of deeper meaning that flows from their writings. The "what" of their writing is important, but so too is the "why." To look beyond just the data of the letters, beyond the names, dates, and written accounts, is to understand how soldiers made sense of their experiences and situations. Historian Jay Winter has written at length about World War I as a transformative force in the history of memory, arguing that the rise of writing prompted by the war constituted the first "generation of memory in the modern period" [1]. Ground-level war accounts are ubiquitous now, but what seems intuitive today was novel a century ago. To have so many people contributing to the documentation of a war was a new phenomenon that sprung up during World War I, and one that shaped how future conflicts have been documented and studied. Historian Jennifer Keene estimated that nearly twenty percent of the American military in 1917 was functionally illiterate, making the vast amount of firsthand war experiences all the more impressive [2]. War -- and, more to the point, its legacy -- was no longer the domain of the educated, as more than ever before, the smallest voices mattered. The stories of the poor and the elite live side by side in the historical record equally weighted despite the backgrounds of those who penned them. The shells, bullets, and gasses of World War I destroyed with a macabre indifference to the social rank of soldiers in their path; similarly, the history that followed has become one of the status-independent narratives.

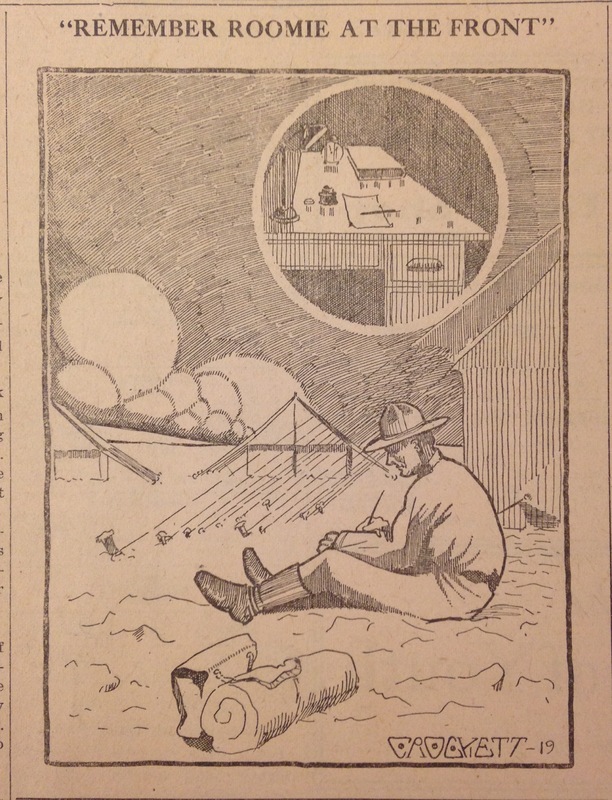

For the soldiers themselves writing from the front, ideas of memory and historical empowerment were probably less important than they are to historians today. More immediate was likely the simple reassurance of human connection that writing offered, made possible more than ever before by globalized forms of relatively rapid communication. The archives are littered with piteous letters from soldiers who ruefully count the number of days since they last received any word from home. Similarly, there is no shortage of soldiers complaining to family members about how brief the last letter they received had been [3]. Whether a temporary distraction from the horrors of the war or a dose of the familiar in the strangeness of a foreign continent, letters gave soldiers something constant to anticipate.

While they pined for lengthy, detailed letters from friends and relatives, soldiers' letters home were frequently brief and cursory. Much of that owed to censorship, but the disparity in communication may have also signaled something even deeper than a hesitancy to include distressing information. Perhaps soldiers saw their letters home simply as a means of letting their families know that amidst the near-constant dangers of life on the front, they were still alive. Perhaps the longing for information from home while relaying little from Europe was an unconscious signal that despite the bravado with which they had left for the war, soldiers felt scared, overwhelmed, and out of place. To the men and women who wrote them, the mere act of writing and receiving letters may have been more meaningful than the actual content within.

Obviously, the "what" of World War I is gripping. The soldiers who believed that their experiences in the trenches and battlefields of the Western Front were incomprehensibly horrifying, all things considered, were probably right. That doesn't stop their accounts from being any less fascinating. If anything, the silences urge us to attempt a reimagining of World War I. Instead, trawling soldiers' writings for hidden clues about how they saw themselves and their situations doesn't have to take away from how captivating the stories themselves are. If anything, the two accentuate each other. The writings set the stage, provide the characters and move the plot along, while the deeper narratives shade in the colors and nuance the mood. Can historians know what life was like for the men and women who endured the battles of World War I? Even if the answer is no, the picture that results from the sources left behind is a rewarding one.

Notes

Please click images for full descriptions and citations

[1] Jay Winter, Remembering War: The Great War Between History and Memory in the Twentieth Century (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006), 18.

[2] Jennifer D. Keene, "Fighting the Great War: Reconsidering the American Soldier Experience," Historically Speaking, vol 13 no. 1 (Jan 2012), 8.

[3] For example, Harry Clippert, a soldier whose first archived letter home includes a facetiously "very stern reprimand" to his fiance for the brevity of her previous letter. Harry Clippert to Ethelyn, March 24, 1918, Clippert Family Papers, Box 1, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.