The Great War and Changing Gender Roles on Campus

“That comfortable balance of the sexes, comfortable, that is as far as men are concerned seems in danger of vanishing. It is quite possible that within a year, as many women as men thronging the campus walks. How terrible the result will be can best be pictured by the freshman or sophomore to whom has been entrusted, by his elders now in service, the task of preserving certain long-cherished traditions.” -Unknown Student, Michigan Alumnus.

The sentiment expressed in the excerpt from a Michigan Alumnus from 1918 above captures much of the gender anxieties on campus produced by the war [1]. As male students and faculty boarded ships to fight at the front, the role of women at the university expanded beyond traditional bounds to maintain University activities and support the war efforts. The number of women on the editorial boards of the various student newspapers increased and groups with an all-male membership began to include women. From opera performances to articles in the literary publications, women at the University of Michigan thought to pave the way for future generations of female students to participate in every facet of university life.

In 1917, an anonymous female student wrote for the student paper the Inlander, predicting the increased role of women should the United States enter the war. “If the war lasts long enough to involve heroic effort on the part of the women of the nation, Michigan students will come back much less inclined to scoff at co-education than when they left; the opportunity to justify it is open to the women of this university as never before. [...] There will be an era of shiny noses and uncurled hair, because there will be no men to notice the lack of powder and marcel curls, and the girls will be too busy to attend to such minor details. All in all, it will be a great day for the feminists [2]." Her essay is followed by a male student’s, Frank F. Nesbit’s, perspective. Nesbit argued or better hoped, that not much would change when it came to women on campus. His fears that the revolutionary ideas of what he refers to as parlor feminism would take hold on campus is clear from his essay. “War is a man’s affair. Men organize it, and men fight it … It will be several years before this country will see any such widespread invasion of industry by women as has occurred in Europe. But blind to this fact, ‘parlor feminists’ in this country are already talking of the coming revolution and some ideas seem to have filtered into our community [3].” Moreover, the fact that the female student desired to remain unnamed while Nesbit has no qualms adding his name to his essay, suggests that women could not freely express their opinion on campus. Indeed, female students more often than not were excluded from clubs and activities on campus. The war changed this, at least in part.

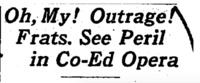

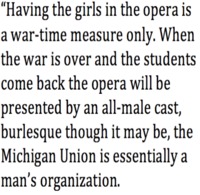

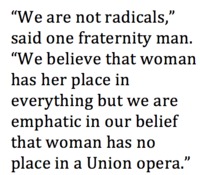

One of the male-only clubs on campus was the Michigan Union. The Michigan Union was founded in 1903, as " a union for all Michigan man, graduates, undergraduates, faculty, and regents [4]." It was during the war that the Michigan Union began to include women at least in some of its activities. This change was a controversial issue. The most visible and divisive debate was about female participation in the yearly Michigan Union Opera. The Michigan Daily reported on the issue as the discussion unfolded, and the Union contemplated whether to allow women to perform in the annual opera for the first time. The issue was important enough that even Detroit Press took up the issue. What is most important about this debate is that it highlights some of the concerns of male students.

The editors of the Alumnus took issue and saw “the fuss” to be “a bit medieval in the face of what women have been accomplishing during these days of war” [5]. Still, the editors viewed the Michigan Union Opera to be an “essentially masculine undertaking,” and more generally that in “public and semi-public undertakings the men and women, so far as seems practicable and desirable, should lead their lives separately.” [6]. But in light of the war female participation, although undoubtedly controversial, was “an emergency question.” Most who wrote in favor agreed that the change would only last for the duration of the war [7]. The opera was one of the Union's important fundraising tools, and its income made up a considerable amount of the organization’s budget. The organizers feared that a poor opera would decrease revenues.

Since the war had increased its overall expenses, a success was ever more important. But perhaps including women would just be the right publicity stunt. The editors of the Alumnus alerted that the opera had been subpar in recent years, and “the public might not see fit to patronize this year’s Opera as well as in the past.” Making a radical change would no doubt make people curious [8]. The opera itself, a war themed undertaking titled “Let’s Go,” was based on the book by a Michigan alumnus Albert L. Weeks, '10 of Detroit, with music composed by Earl V. Moore, who had graduated from the university in 1912. The fact that it was alumni and not current students who wrote and composed the music also defied traditions, but no one seemed to care. Despite the idea of bringing women onto stage causing a great debate published even in the Detroit papers, women eventually performed in the opera.

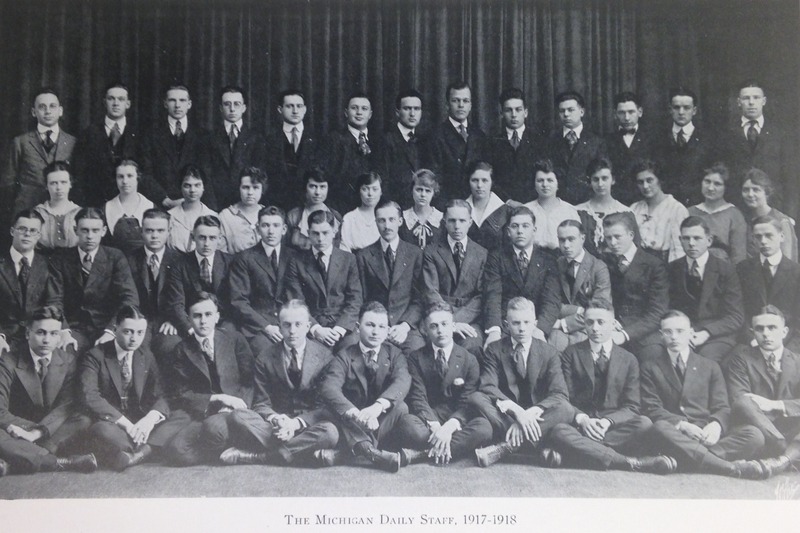

The male student population had decreased in the fall of 1917, leaving the Michigan Daily in need of additional staff. Consequently, the editorial board recruited a significantly higher number of women. Whereas in 1916-1917, the Michigan Daily staff only had four women, the 1917-1918 female staff increased threefold, with a total of 15 women writers. Some of these women included Vera Brown (66), Doris M Ball (61), Dorothy E Patterson (96), Margaret H. Cooley (91), and Mildred C. Mighell. Thus, as women performed in the Union Opera, they also made headway in other areas of traditionally male-dominated groups, including some campus newspapers and magazines like the Michigan Daily, Inlander, and Gargoyle [9].

To commemorate the contributions of the Michigan women during the war, the 22nd volume of the Michiganensian wrote a section recognizing that they stepped up, filling staffing positions where needed in 1918. Within the 1918 Michiganensian, a special section was devoted to the “Women’s College Year,” informing its readers that “Every technical detail formerly thought beyond the province of women journalists has been mastered by them in this war created emergency” [10].The editorial staff of the satirical journal Gargoyle was joined by four women in the 1917-1918 school year, including Jeanette Kiekintveld (‘18), Alice M. Burtless (‘18), Mrs. Clarence Baker Goshorn (‘19), and Margaret Jewell (‘20). The Inlander, the campus literary journal, provided yet another platform on which Michigan women showcased their strengths as journalists. Here women presented their opinions on important issues of the time [11].

Another, more direct way women contributed to the war effort was through all-female organizations. One of the most active all-female groups on campus was the Women’s League, which dedicated much of its activities toward sewing and filling comfort bags for American soldiers. Enrollment at the university, although it had decreased overall due to male faculty and students going abroad, had increased in terms of the number of nursing students, a large part of whom were female. Women also held banquets, held fundraisers, and ran Liberty Loan campaigns across campus all of which were invaluable to the war effort. Moreover women worked with the-Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) and the American Red Cross (ARC). (Please read here for an account of some of these activities).

Women entered the postwar era with unprecedented leverage in the fight for gender equality. Between the 1918 armistice and 1920, Germany, Ireland, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Belgium, Austria, the United Kingdom, and the Netherlands gave women the right to vote. Just as suffrage movements made vast strides all across Europe, women in America -- and in Ann Arbor -- attempted to translate their wartime contributions into civil rights. The wartime suspension of lobbying had cut down on the most direct suffrage activism, which combined with public demonstrations by radical feminist groups to slow public acceptance of the movement [12]. American suffragists were able to use the war to their advantage, as the federal government -- and subsequently the states -- ratified the nineteenth constitutional amendment in the summer of 1920.

At the University of Michigan, though, civil rights were only one arm of the emergent postwar gender issues as women sought an even social footing on campus. Female students had done their part during the war and seen gender roles shift towards equality during the conflict. Following the armistice, their new goal was to ensure that those changes would be permanent. While women continued to seat student paper editorial boards, not all of their efforts were successful. For example, female performers in the cast of the Michigan Union Opera proved to have been a wartime exception.

Michigan campus' gendered divide became even more visible with the completion of two iconic buildings: the Michigan League and the Michigan Union. Envisioned as a "democratic alternative to fraternities," the Michigan Union building was to be the first institution of its sort on any American college campus. A place for students to eat, swim, and relax, the Union was steadfastly male, since administrators believed that the Martha Cook and Helen Newberry dorms provided a sufficiently similar function for women [13]. In response, female students rallied to raise funds for the future Michigan League as a female counterpart to the Union. Though the League was successfully funded and built by 1929, the gendered divide on campus remained firmly in place.

Notes

Please click images for full descriptions and citations

[1] "University Women and the Opera," in The Michigan Alumnus, Vol. 24 (1918), 263.

[2] Anonymous female student, "The University Next Year," The Inlander, Vol. xix (1917), 7.

[3] Frank Nesbit, "The University Next Year," The Inlander, vol. xix (1917), 12.

[4] Henry Moore Bates, The Plan and Purpose of the Michigan Union, (Ann Arbor, The Richmond & Backus co., 1905), 2.

[5] "University Women and the Opera," in The Michigan Alumnus, Vol. 24 (1918), 263.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid., 270.

[8] Ibid., 263.

[9] Michiganesian (1917-1918), 34.

[10] Ibid., 45.

[11] Ibid, 58.

[12] Jensen, Kimberly: Women's Mobilization for War (USA), in 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War, ed. by Ute Daniel, Peter Gatrell, Oliver Janz, Heather Jones, Jennifer Keene, Alan Kramer, and Bill Nasson, issued by Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin 2014-10-08, 8-9.

[13] Howard Peckham, The Making of the University of Michigan 1817-1967 (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1967) 170-1.