A World at War, a Campus Unfazed: Pre-War Student Life

”No one seems to know where we are or what kind of course we are taking.” Thomas F. McAllister [1]

If an undergraduate at the University of Michigan today found himself transported nearly a century back in time, the campus climate he’d find himself in wouldn’t seem all that different from the one he left. In 1916, Michigan students were still rabid about their university’s sports teams. Fraternities dominated the social scene, and though violence had long subsumed Europe, life carried on uninterrupted. Exams, dates, and careers were at the forefront of students’ minds then as they still are now. The Diag, though absent the hammocks and frisbees that have become twenty-first-century staples of an Ann Arbor summer, appeared much the same before World War I as it looks today. Before the genteel pace of college life gave way to the militaristic routine and discipline of wartime, the University of Michigan of the past would have been easily recognizable to anyone who has recently set foot in its libraries, sat in its lecture halls, or walked its tree-shaded sidewalks. Indeed, many of the buildings that remain campus landmarks were built during the years immediately preceding World War I. Hill Auditorium, the Natural Science Building, Lane Hall, and Alumni Hall -- today the Museum of Art -- were all funded and built between 1910 and 1916, as were the Helen Newberry and Martha Cook dorms. Even in 1917, university heads continued to earmark funds for new construction projects before the realities of wartime halted work on the Michigan Union and a new University Hospital [2].

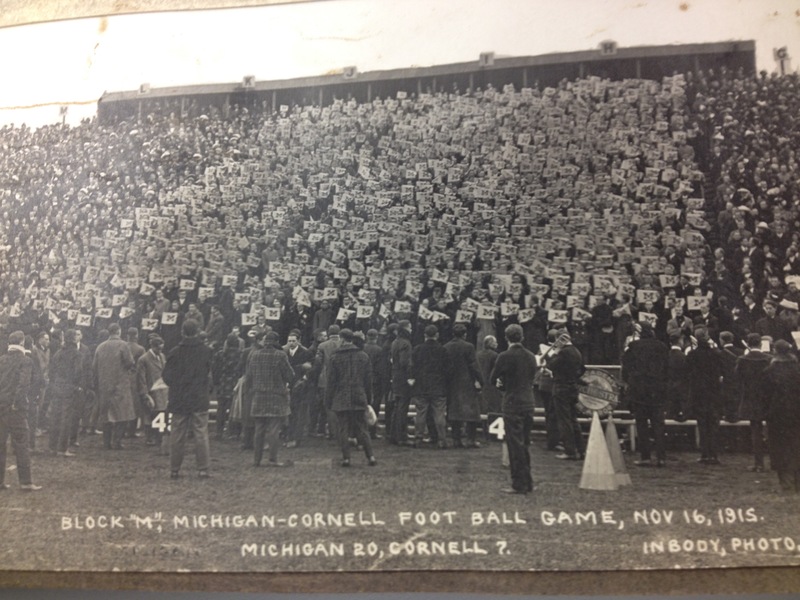

As the winter academic semester began in January 1917, life at the University of Michigan carried on as usual. The conflict overseas had ground to a stalemate. Trenches crisscrossed the French countryside and years of gunfire had decimated its towns. The Allies and the Central Powers found themselves incapable of any progress across the barren No Man’s Land of barbed wire and artillery craters that separated one side from the other. As the conflict crept towards its third year, one notable world power remained decidedly out of the picture. Arthur Zimmerman had not yet sent the infamous telegram that would provoke the United States to enter the fray, and behind the committed neutrality of President Woodrow Wilson, Americans watched from across the Atlantic as Europe moved toward a total war. Still, campus remained largely unfazed. Senior Edward Mack began his final set of classes, Professor Bursley wrote a set of extraordinarily difficult French exams, and although the number of students enrolled in German language courses had taken a slight dip, campus, like Ann Arbor and the rest of the country around it, remained fairly unaffected by the devastation facing Europe [3]. A report from the student government at the end of 1916 claimed that “Perhaps the most troublesome single issue [on campus] is the general manner of student dances ... the situation has long been serious and has latterly been growing more so”[4]. Amidst the dances, parties, classes, and the recent successes of Fielding Yost’s football team, the war on the other side of the Atlantic seemed strikingly at odds with the leisurely lives of Michigan’s students and teachers.

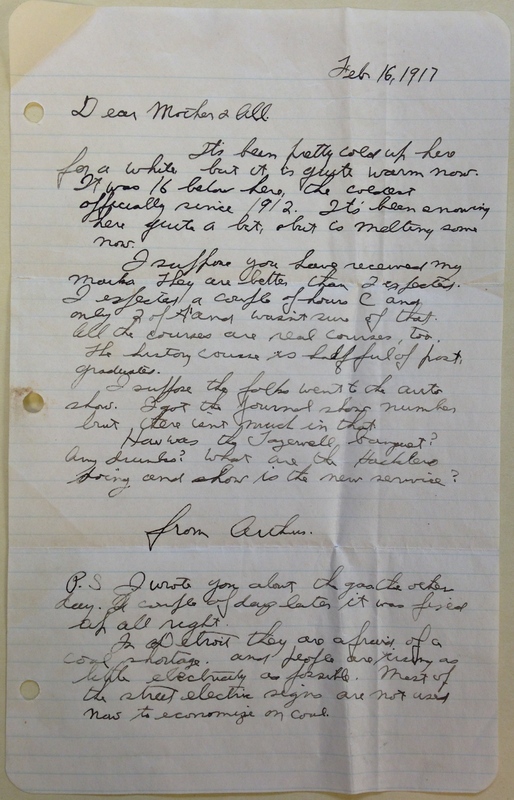

Though a current of war awareness flowed in some capacity across campus, on the surface it was school as usual. The winter of 1916 and 1917 was an unusually cold one, and the letters home from Michigan students are littered with complaints about the sub-zero temperatures and deep snowfalls. Arthur Ehrlicher -- a senior who would enter the Army as a machine gunner after graduation a few months later -- wrote to his parents in February, lamenting his decision to enroll in three eight o’clock courses [5]. Ernest B. Drake, an engineering student, frequented his professors’ office hours and struggled with indecision about whether or not growing a mustache would damage his appeal with girls on campus [6]. "We did not have radios and televisions to keep us in immediate touch with events at home and abroad," wrote one Michigan alumnus and soldier in a memoir. "Most students did not subscribe to newspapers or read them with any regularity. We lived in a kind of informational backwater. The world beyond our immediate horizons was remote, and its actions were slow to impinge on the provincial consciousness"[7]. Girls, grades, and weather: these, not the war, were the most pressing concerns on students’ minds in 1917.

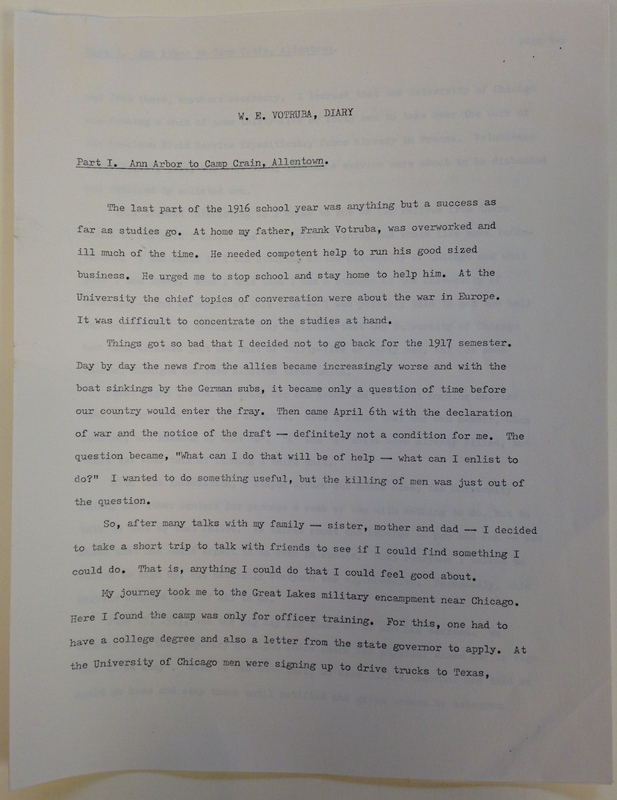

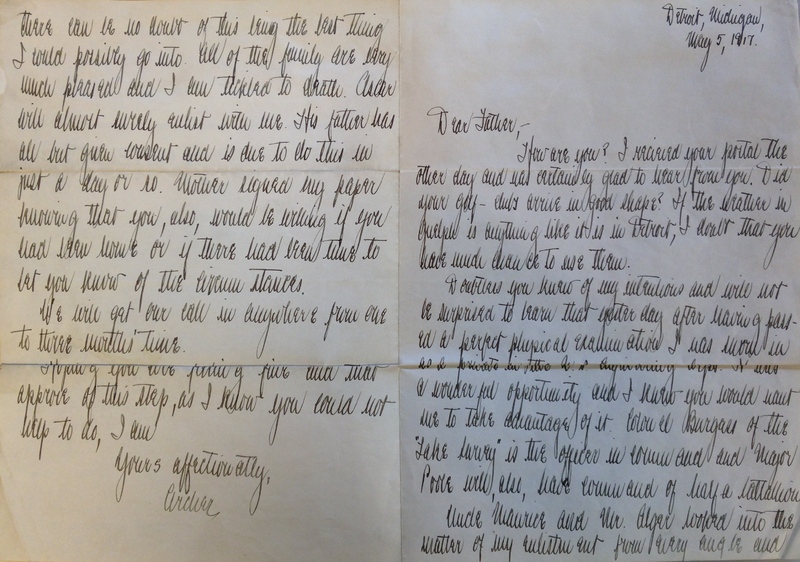

However, a handful of prescient students saw the growing inevitability of American involvement in Europe. William Votruba, a student from Traverse City, later wrote, “It was difficult to concentrate on the studies at hand. Things got so bad that I decided not to go back for the 1917 semester,” adding, “it became only a matter of time before our country entered the war.” According to his writings, his uncertainty about the future was common across campus: “Most everyone I talked to wanted to sign up, but naturally everyone was apprehensive”[8]. Archer Ford Hinchman, a Detroit teenager with an acceptance letter to Michigan, decided to enlist in the military rather than begin his studies and risk an interruption down the line. He later returned to Ann Arbor and graduated in 1924 [9]. This decision to postpone education wasn't confined to just a few: there were 6057 students at Michigan in the fall of 1917, down from 7517 the year before [10].

As absorbed as U-M undergraduates may have seemed in their studies and their sports teams, they lived less in a bubble than it seems. Conversations about what was happening in Europe had bubbled below the surface on campus since 1914, only growing louder as time passed. Even though Michigan’s administrators were reluctant to take proactive steps toward war preparedness before 1917, students were aware of -- and worried about -- the distinct possibility of being called overseas before long. Even if the war initially took a backseat to more present issues, it remained firmly lodged in the collective campus imagination. As professors like William Hobbs began to speak increasingly often about the perils of isolationism, more students became convinced of not only the inevitably of American military involvement but also of its necessity.

Notes:

Please click images for full descriptions and citations

[1] Thomas McAllister to parents. May 6, 1917. Folder 1. Thomas F. McAllister Papers. Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

[2] Howard Peckham, The Making of the University of Michigan (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1967), 132-135.

[3] Ernest B. Drake Papers. Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan; Jonathan Marwil A History of Ann Arbor (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1991).

[4] Annual Report of the Senate Committee on Student Affairs, 1915-1916, Box 1, Folder 1 Senate (University of Michigan) Records. Bentley Historical Library. University of Michigan.

[5] Arthur Ehrlicher letter to parents, February 16, 1917, Arthur Ehrlicher Papers, Folder 1, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

[6] Student Diary, October 17, 1916, Ernest B. Drake Papers, Box 1, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

[7] Carl E.W.L Dahlstrom, Sent to Hell from Ann Arbor: A College Student’s World War One (Portland: Quaker Abbey Press, LLC), 15.

[8] William Vortuba Memoir, undated, William E. Vortuba Papers, Box 1, Folder 4, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

[9] Ford Arthur Hinchman letter to father, 5 May 1917, Ford A. Hinchman Papers, Scrapbook Vol. 1, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

[10] Peckham, The Making of Michigan, 144.