Life on the Front: Soldiering

“No one who did not go through the World War can have the same faith, or know what the real meaning of WAR is. To help your comrade you must suffer with him. To work for A Great Cause like the one we went through in The World’s War, one had to give all his strength and suffer with one’s fellow soldiers" [1].

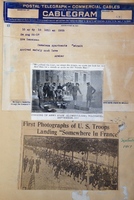

Following training at camps like Fort Sheridan and Camp Custer, Michigan soldiers boarded ships to begin their service abroad. The voyages across the Atlantic were marked by long hours of boredom and not a few cases of seasickness. Soldiers passed the time gambling, talking about machine guns and learning French. At times, the sightings of sea animals like whales and porpoises provided some diversion. With little to do except endure lifeboat drills, nausea-inducing sea waves, and the weariness of potential submarine attacks, arriving in France brought relief to the travelers and a renewed excitement for what was next. One such traveler Gilbert Ross, who would go on to become an ambulance driver, recounts to his mother “Well, here I am safe and sound. Some trip! Those last three days were anything but pleasant" [2]. Once soldiers arrived abroad, many commented on the beauty of their environs. From weather to architecture to a city’s entertainment, soldiers would be sure to include their take on their new locale in letters home to family. Below are excerpts from a few Michigan soldiers comments on their surroundings.

"Another very beautiful day- one of the finest I have ever seen- pure sunshine all day, and soft air, unlike anything I have ever experienced in America... Find I am enjoying these strolls very much, and nothing could be finer than this mountain air. - Samuel D. Pepper, March 23, 1918.

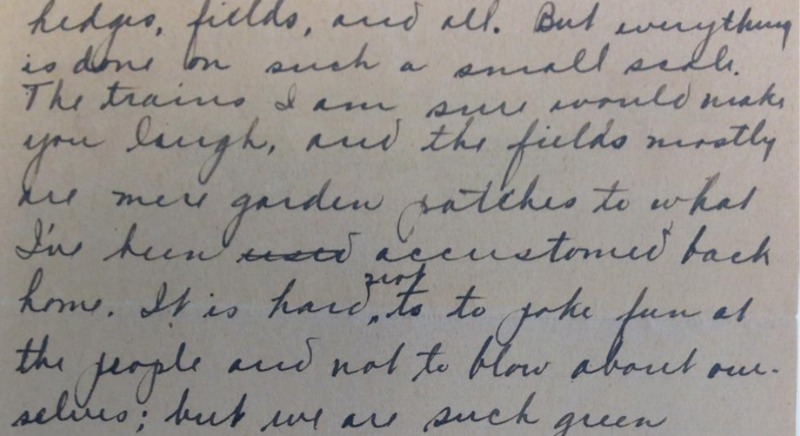

Once arrived, soldiers received a billet, or lodging assignment, in a French or English village. Traveling from village to village allowed them to experience the landscapes, upon which they often remarked. Kenneth Easlick recalled “I enjoyed the rail trip immensely. All of England that I saw was as neat as a pin, little brick houses, hedges, fields, and all" [3]. Easlick also makes a humorous comparison between how the fields in England were so tiny compared to those in America.

Many Michigan men first landed in Paris and were able to enjoy the sights and wonders of the city for a couple of days prior to joining their comrades at the front. For others, Paris would become a destination once they were on leave. And while the American military command did not grant regular permissions to soldiers to visit Paris, many men did get a chance to visit while serving in France. Many of the letters and diaries comment on these visits and highlight the perceived social differences. For instance, some soldiers commented on how the women in France differed from those in America. Samuel D. Pepper, while in Dijon, recorded in a diary entry on April 9, 1918 “The market women are very business-like, bright and talkative, much as one sees in country towns at home. The women were as well dressed as those at home"[4].

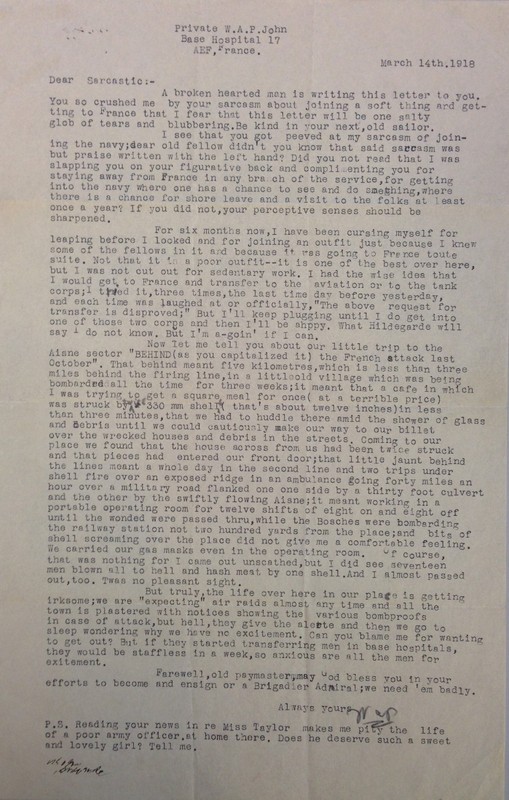

While in cities, Michigan soldiers managed to stay in touch with their peers from the university. The Michigan Union was instrumental in this. It had the names and addresses of around seven hundred Michigan men abroad. The Michigan Alumnus reported that Michigan dinners were held in Dijon and Paris during the war [5]. The first took place in Paris on June 1st in the city club, Cercle Artistique et Litteraire. French and American soldiers were in attendance. Tensions were high. The City had been experiencing raiding and shelling since May 27th. Moreover, rumors circulated that the “Boches,” referring to German soldiers, were headed to Paris and beginning to enter Chateau Thierry; yet attendees managed to enjoy the dinner party nonetheless. For example, Michigan Professor C. B. Vibbert wrote to University of Michigan President Hutchins, “Never did I go to a banquet with such mingled sentiments, a curious feeling that, in the midst of our supposed joviality, we might be suddenly called upon to flee for our lives" [6]. The next three dinners would take place in Paris, and the Michigan Alumni Association hosted a weekend in Dijon for Michigan men. One of the highlights of this weekend was the performance of a Michigan Union Opera, written by W.A.P. John. “Dijon is the most distinct centre of University of Michigan interests and spirit outside of Paris; in fact, the spirit is, I believe, more concentrated than in Paris itself” [7]. Overall the parties hosted for Michigan soldiers in France are representative of an attempt to uphold a communal spirit among alumni, faculty, and students. Throughout all of the bombings, raids, and impending attacks, Michigan soldiers came together celebrating their school pride and found comfort in their fellow Michiganders, who were a familiar sight in all the unknowns of the war [8].

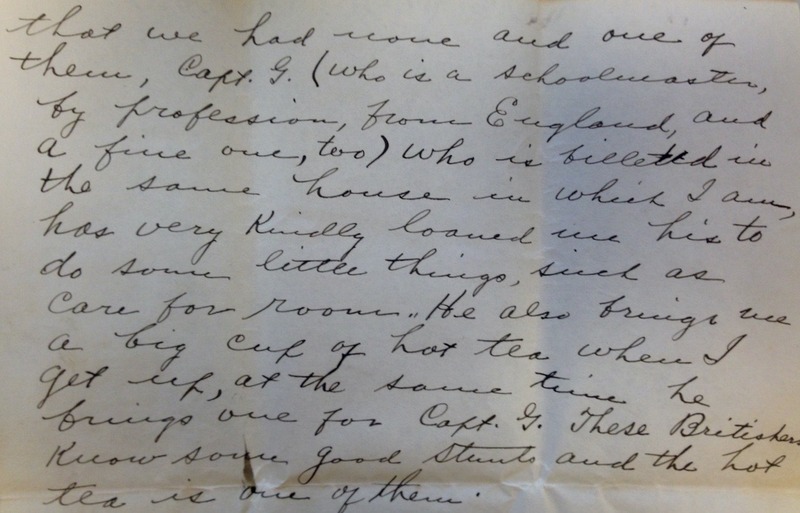

Once soldiers arrived at the front the everyday details, so prominent in the earlier letters disappear. We encounter a silence as soldiers avoid writing about specific war activities. In their letters the men would comment on how hard and grueling the work was, air a few speculations about what was going to happen, and highlight their feelings of camaraderie and loyalty to their unit. Even the diaries, which would not be subject to censorship, are summary accounts and more often than not include only generalized statements. For example, Samuel D. Pepper, a Judge Advocate with the U.S. Army, wrote on Tuesday, April 16, 1918, “Have had several matters to attend to this week -- summary special court cases nothing particular to note in this area” [9]. This lack of detail on his work remains the norm throughout his diary. Instead like letters, many journals focus on the weather, recreational activities, engagements of friends. Notes on war activities or sentiments tend to be of the nature that “war is hell” or a speculation on where the Boches are and where they will go next. Life on the western front for some higher ranking men meant a certain amount of luxury. Second Lieutenant Harry Crawford of the 118th Infantry served with British soldiers and even learned advanced British infantry techniques while his unit was under British command. At one point a friend of his, a British officer offered to share his servant so that Crawford could enjoy the perks of having his room tidied and a fresh pot of morning tea [10]. Michigan soldiers were serving with the Polar Bear Expedition in Russia, in contrast, had few luxuries and were accustomed to having to attend to their affairs. For example, Walter McKenzie states in a letter dated July 17, 1918. “We have to depend upon ourselves now for everything except cooking our own meals. We must wash our own clothes and towels and keep them clean" [11].

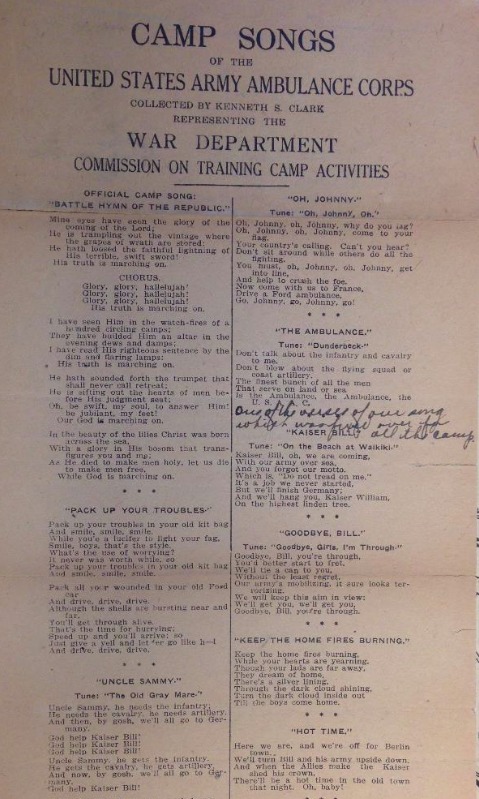

When soldiers do remark upon wartime activities their comments express a sense of national duty and loyalty to the men in their units. A general spirit of camaraderie may explain this excitement and sense of responsibility they felt for their peers. Soldiers were quick to comment on the spirit and camaraderie among troops and the bravery of their fellows in letters and diaries. To the right is a list of songs troops would sing if they were a member of the U.S. Army Ambulance Corps, like Kenneth Easlick. The song “The Ambulance” highlights the strength of the camaraderie, not only within the Army as a whole but in subunits of the army as well [12]. A letter of Samuel D. Pepper reinforces the centrality of camaraderie to military experiences. For example, Pepper describes, in a letter dated November 20, 1918, how the 1st, 2nd, and 89th divisions fought in a “memorable attack” and how the soldiers showed “high courage, devotion to duty, and disregard for the innumerable hardships encountered.” He says that they “made for themselves a place in the history of our country” [13]. In terms of his sentiment of the enemy, he recounts their actions as “a strong enemy resistance” and as “stubborn resistance.” Pepper also notes on September 5, 1918, that he believes the “fighting spirit” is integral to successful battles and is concerned whether the training of troops has been “sufficiently complete to establish proper teamwork between all its elements” [14]. These comments show the great emphasis on teamwork in the army’s subunits, and cohesiveness and songs strengthened this sense of camaraderie and spirit among the troops. They can also help explain why in the midst of raids and bombs Michigan soldiers were still finding a way to come together for parties [15].

Still will mostly silent about the violence of war, the horrors of battle and fears of individual soldiers at times shine through. It might be argued that, these shared experiences of attacks and deaths, as they are recounted here by soldiers, played a substantial role in the sense of camaraderie felt by troops. The bonds between soldiers was a comforting reality, which at times meant that soldiers were eager to rejoin their troop, even when opportunities for leave would present themselves. One such soldier, Harry Crawford expressed a desire to be reunited with his troop when he was sent away from the front to receive advanced infantry training. All in all, these bonds would prove long-lasting for Michigan soldiers. The high number of reunions held following the war are a testament to this. As they returned to campus following the armistice in 1918, the university implemented many changes that would accommodate returning soldiers academically and socially, allowing them to begin or complete their education. Even when the war finished, those who had served together abroad would still host reunion parties, commemorating the University of Michigan’s contribution during the war and celebrating the bonds forged in the midst of the war. For example, Kenneth A. Easlick of the U.S. Army Ambulance Corps Unit 591 notes the celebrations that took place at the Michigan Union in years following the war [16].

Notes

Please click images for full descriptions and citations

[1] Kenneth A. Easlick Papers, Memoirs of 591 in The World War - DeWitt C Millen

[2] Letter from Gilbert Ross to his mother, dated July 6, 1917, Blanchard Family Papers (ca. 1835-ca. 2000), Box 56, Gilbert Ross’s Letters beginning with 1917, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

[3] Letter from Kenneth Easlick, dated Sept 16, 1917, Kenneth A. Easlick Papers 1924-1979, Box 1, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

[4] Samuel D. Pepper Diary, Entry from April 9, 1918, Samuel D. Pepper Papers, 1893-1952, Box 2, Correspondence, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

[5] "Letters from the Front, Excerpt of a letter from Professor C. B. Vibbert to President Hutchins," The Michigan Alumnus, Vol. 25 (1918/1919), 34.

[6] Ibid., 33.

[7] Ibid., 35.

[8] Ibid., 33-35.

[9] Samuel D. Pepper Diary, Entry from Tuesday, April 16, 1918, Samuel D. Pepper Papers, 1893-1952, Box 2, Correspondence, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

[10] Harry Crawford, World War 1, Box 1, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

[11] Letter from Walter McKenzie to his mother, dated July 17, 1918, Walter I. McKenzie Polar Bear Expedition papers, 1918-1945, Box 1, Folder 4, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

[12] "The Ambulance," in Camp Songs of the United States Ambulance Corps, Kenneth A. Easlick Papers 1924-1979, Box 1 U.S. Army Ambulance Corps, Unit no. 591 Papers ca. 1924-1964, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

[13] Samuel D. Pepper Diary, Entry from November 20, 1918, Samuel D. Pepper Papers, 1893-1952, Box 2 Correspondence, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

[14] Samuel D. Pepper Diary, Entry from September 5, 1918, Samuel D. Pepper Papers, 1893-1952, Box 2 Correspondence, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

[15] Samuel Pepper Argonne attack

[16] Kenneth A. Easlick Papers 1924-1979, Box 1, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.