Antiwar Voices on Campus

‘One of the biggest fights in the history of labor is now going on in California,’ said Miss Emma Goldman yesterday afternoon as she passed through Ann Arbor on her way to the workers’ relief mass meeting to be held in Carnegie Hall, New York. ‘The chamber of commerce of San Francisco is waging a campaign against organied (sic) labor and has started by arresting some of the most prominent labor men and have charged them with murder in connection with the preparedness parade bomb explosion of July 22 in San Francisco of which they are absolutely innocent.’

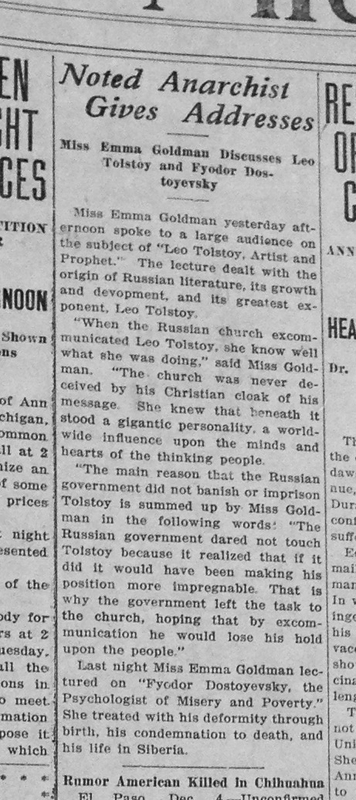

Thus read an article printed in the Michigan Daily on October 30, 1916 [1]. Goldman’s subject the night before was an event soon recognized as a pivotal moment in the history of the labor movement and radical politics. The San Francisco Preparedness Day Parade bombing and trials were an emphatic demonstration of an emerging link between, on the one hand, the open-shop interests of big business and the preparedness effort, and on the other, labor’s fight for union control and the antiwar cause. In Goldman’s estimation, the heaping of blame for the San Francisco catastrophe on the unions was a blatant demonstration of the corruption of the business community. Conspiring with the San Francisco Law and Order Committee, the San Francisco business leadership was able to direct public outcry against the bombing into an ongoing campaign for the destruction of the closed shop.[2] In her talk the night before, Emma Goldman had spoken of the prejudice of the legal system against the working classes, big business’ control of juries, and her fight to gain legal protection for those accused. It seemed that the atmosphere of war preparedness and the threat of impending American involvement in Europe, Goldman maintained, gave cover to insidious and wide-ranging violations of civil liberties on the part of the government.

By the fall of 1916, the discussion on campus over American entry into World War I was becoming consistently more urgent, controversial and heated. At the University of Michigan, as throughout the nation, public opinion was divided into two camps: those on the side of “Preparedness,” and those against it. The pages of the Michigan Daily featured regular notices of fora to be held on the question of compulsory military training as well as lengthy editorials from students, alumni, and faculty on either side. It became increasingly clear that those in favor of “Preparedness” were winning—yet those few oppositional voices left remained strong and intractable, at least for the time being.

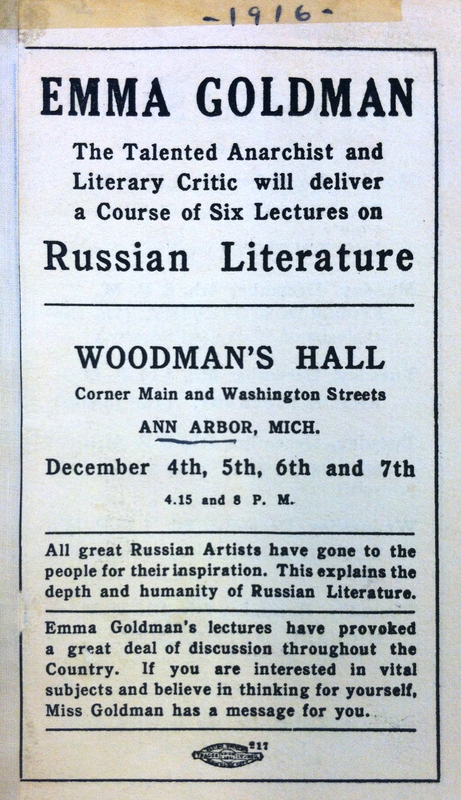

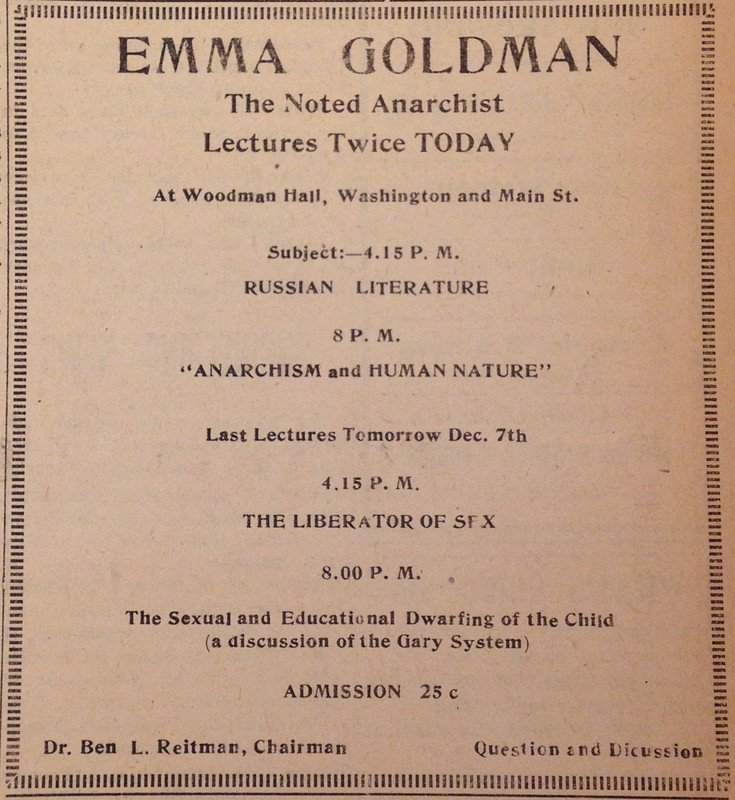

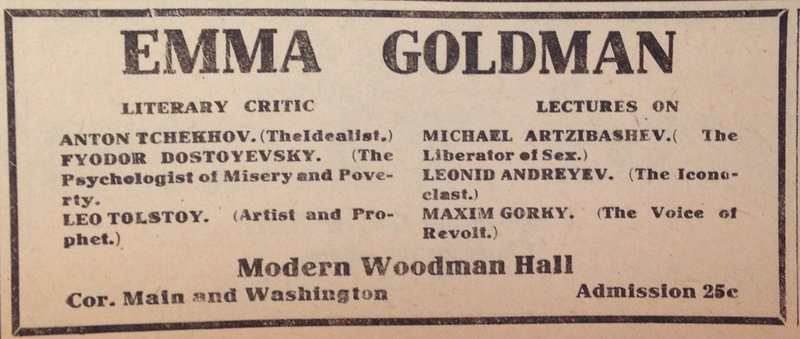

On December 7, 1916, Emma Goldman held her last lecture in Ann Arbor prior to American entry into the war. Her topic was an apparently benign one: Russian literature, and its relationship to anarchism. For her last lecture, on “The Sexual and Educational Dwarfing of the Child (A Discussion of the Gary System),” three hundred people crowded into Woodman’s Hall, a small, cramped space above a shopfront on the corner of Washington and Main Street. Reminiscing in 1932, Agnes Inglis recalls that a Preparedness meeting was being held on the same night in Hill Auditorium. As the crowd—composed of more than ten times as many people as came to hear her beloved Emma—poured into Hill Auditorium, Inglis, her lifelong friend Margaret Grennell, and Goldman’s companion, Ben Reitmann, stood on the steps of Hill and passed out a five-cent booklet by Emma Goldman. Its title: Preparedness: The Road to Universal Slaughter. “We passed that out to people going into a ‘Preparedness Meeting, who wanted war.” Inglis recalls, “We didn’t.”

Inglis, organizer of the lecture tour, decried the fact that the University had been unwilling to provide a space in which Goldman could speak. Following Goldman’s visit, she published an article entitled “Free Speech on the Campus of Ann Arbor,” in the January 1917 issue of Mother Earth, the anarchist magazine published by Goldman and co-worker and companion Alexander Berkman. Disappointed as she was with the lack of free speech exhibited on campus, Inglis seemed pleased with the surprising results of Goldman’s lectures: significant publicity and high attendance. “She spoke twice a day, afternoon and evening and strange to say, the lectures were all well attended, which is a tremendous feat in as much as the students are worked to death with lectures and everyone foretold that eight meetings in Ann Arbor would prove a failure.” Not only did Goldman’s lectures bring sizable crowds, but the speaker herself received invitations from “all sorts of quarters least expected, at fraternities and sororities, the Gamma Phi Beta and the Alphi Phi entertained her. Then the boys’ house club, the Eremites and last, but not least, Dr. Ben spent one noon at the Lambda Chi Alpha.” After Goldman’s talk, Inglis reported, as many as fifty University students accompanied Goldman and Inglis to 1340 Wilmot St., Inglis’ house and the virtual headquarters of Ann Arbor radicals. [3]

Goldman’s visit also received sizable and surprising publicity. Advertisements and announcements were scattered throughout the pages of the Daily all through the week preceding her arrival. Finally—the day after Goldman’s last talk—the Daily published an article entitled “Anarchism Finds Root in Liberty,” recounting her Wednesday speech on “Anarchism and Human Nature.” A brief yet thorough treatment, the article’s reasonable and fair tone, and the lack of comment on the part of the author, seem out of place for a discussion of one of the most despised radical traditions in American history in a period increasingly characterized by intellectual conformity and repression. The enthusiasm and interest shown by these young people changed all my ideas,” recalls Inglis.

All the young people who heard or met E.G. are discussing a good many things now they weren’t discussing before. They are thinking, so are other people. It isn’t a question of agreeing with her all at once, but the fact is important that she inspired so many to think and to face the truth…I felt that that week, with the awakening for so many, was a little Renaissance. [4]

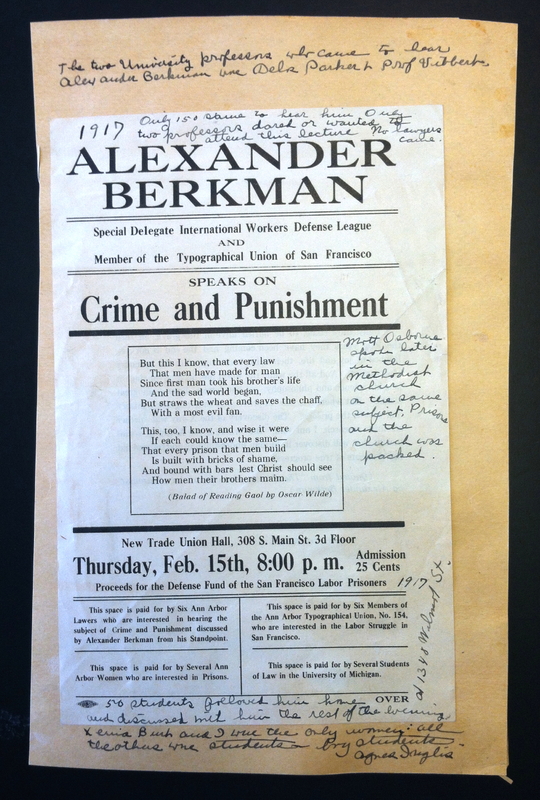

Two months later, Alexander Berkman, anarchist, co-conspirator with Goldman and her lifelong friend, came to Ann Arbor to lecture on the San Francisco Preparedness Day Parade Bombing, this time without Goldman. Curiously, his visit was paid for by a combination of Ann Arbor lawyers, members of the Typographical Union, Ann Arbor women interested in prisons, and law students at the University. Only weeks before the American declaration of war, Berkman’s lecture at the Trades Council Hall on North Main Street drew only 150 audience members. Inglis notes with disdain that only two professors—Charles B. Vibbert, of philosophy, and Dels Parker—“dared or wanted to attend.” Yet some clearly were interested: according to Inglis, 50 students followed Berkman back to Inglis’ house at 1340 Wilmot and talked with him well into the night. The next day, The Michigan Daily ran a report of the lecture, and on February 18, an article entitled “Berkman Thinks Bomb Trials are Frame Up: Anarchist Believes San Francisco Affair is Plot to Terrorize Labor” went to print.

All in all, the treatment of Berkman’s and Goldman’s visits in the winter of 1916-1917 by the University community suggests a comparatively neutral and open-minded campus climate. The University did refuse to grant Goldman the use of a space in which to lecture, and attendance at Berkman’s talk was low. However, in both cases, students made up the majority of the anarchists’ audience—in Berkman’s case, Inglis recalls, the public was University “boys” almost without exception. Moreover, the enthusiasm of those that did attend was significant enough to warrant Inglis’ opening her home to students, for whom a lecture was apparently not enough. Lastly, the wealth of advertising in the Daily and the open conversations printed after the speakers’ talks suggests that even as late as January 1917 the repression that would characterize the war years was only beginning to set in.

[1] The Michigan Daily, October 30, 1916, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

[2] The Pacific Historian, Vol. 28, No. 4, Winter 1984. Subject Vertical Files (“Berkman, Alexander”), Joseph A. Labadie Collection, University of Michigan Library.

[3] Agnes Inglis Papers, Box 28, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

[4] "Free Speech on the Campus of Ann Arbor," Mother Earth, January 1917, Emma Goldman Scrapbook, Agnes Inglis Papers, Joseph A. Labadie Collection, University of Michigan.