Radicalism in the era of “Preparedness”

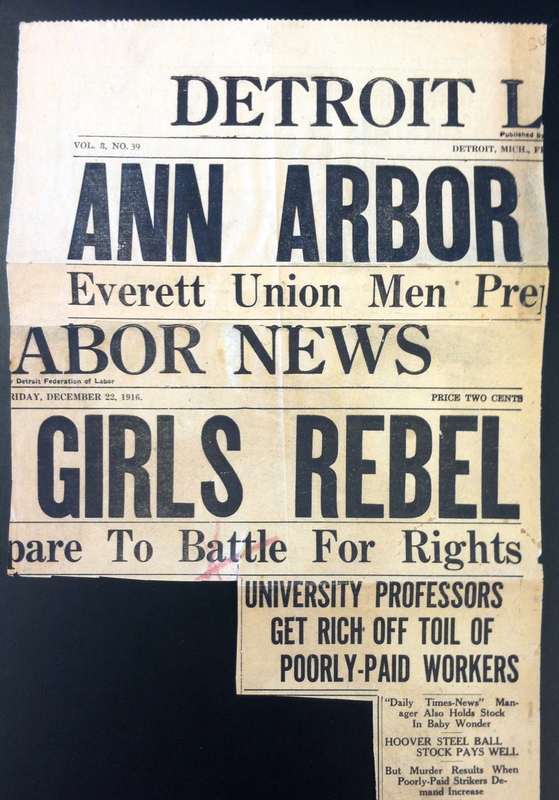

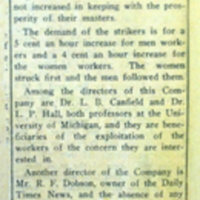

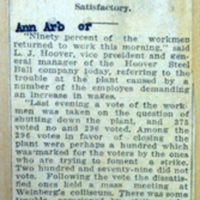

In December of 1916, The Detroit Evening News, Michigan Socialist and Detroit Laber News and announced headlines: STRIKE IN ANN ARBOR, ANN ARBOR GIRLS REBEL. Facing the intractable combination of static wages, a rising cost of living, and increased output levels and company profits, women workers at Hoover Steel Ball initiated a strike. They were soon joined by over 100 of their male counterparts, most of whom were recent immigrants, “Greeks from Greece and wherever else”[1]. Hoover was thriving in war, finding that the Detroit auto industry, deprived of its steady supply of ball bearings from Germany, made an excellent clientele. Workers, developing some semblance of class solidarity, called attention to the fact that their labor had made “semi-millionaires of men who a few years ago were in modest circumstances,” while their own conditions worsened. It was clear, furthermore, who their class enemies were: the list of prominent company stockholders included two university professors and the editor of the Daily Times-News. Hoover and others decried the strike, claiming it was the result of un-Americanism among the Greek immigrant population, and insisting that he paid his workers a fair wage. In this brief moment, the veneer of middle-class gentility that characterized the small university town faded temporarily. Social forces dominating throughout the region—labor unrest, anti-immigrant hostility and sharp class divisions—became briefly visible in Ann Arbor.

News Clippings Discussing the Hoover Strike:

This was the effect of the European war on Ann Arbor industry. That December, Wilson’s request for a declaration of war on Germany was still months away; yet already, the influence of the far-off war on the American national economy was evident. Labor relations nationwide reached all new levels of disruption in the face of the booming wartime economy. As industrial output surged, union membership grew and workers initiated strikes on unprecedented scales: 3,000 strikes in the first six months of war[2].

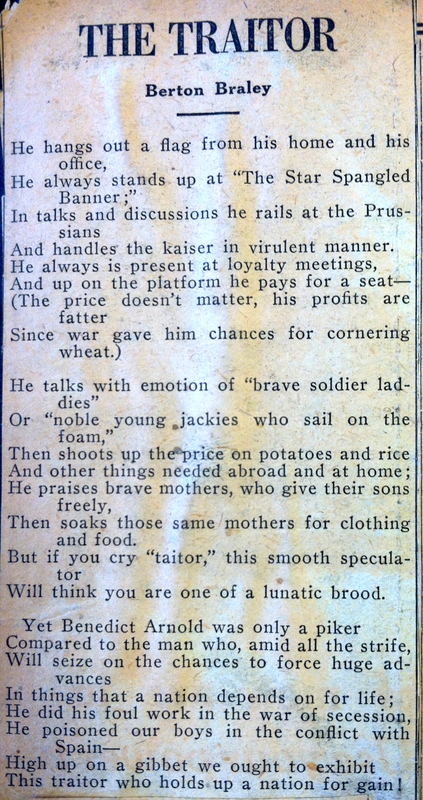

The coming of the war would radically alter the conditions of the American radical’s battle for social change. Not only did the war affect the conditions of workers at home, but the reaction in the political mainstream to socialists’ and radicals’ stance on American entry into World War I ultimately determined the course of the movement’s history. Moderate organizations like the American Federation of Labor were able to use the demands on industry and production created by war to make significant inroads for labor. Formally acknowledging the authority of unions for the first time, President Wilson established the National War Labor Board (NWLB), an organization that would police cooperation between Unions and management. Though this progress was lost along with the NWLB in the anti-radicalism of the 1920’s, it set the stage for the postwar development of industrial welfare capitalism. Yet while the war may have mildly improved working conditions and pacified socialist pragmatists, it bode extremely ill for more radical strains of the movement. When organizations like the Socialist Party of America (SPA) and the IWW adopted a strong anti-war stance at odds with prevailing national pro-war sentiment, they were heavily targeted as “pro-Germans,” foreigners and unpatriotic ingrates.

The wartime climate of hysteria and suspicion only exacerbated the tendency towards nativism and Anglo-Saxon cultural chauvinism that had increasingly characterized American society from the turn of the 20th century onwards. Political radicalism, long associated with immigrants—in particular, those from southern and eastern Europe—now became the defining associative mark of foreignness in the United States for most natives, spelling doom for the acceptance and assimilation of recent immigrant populations. Thus it was no surprise that local news sources blamed the Hoover Strike on the supposed political radicalism of the growing population of Greek immigrants in Ann Arbor. Foreigners—thought of as products of the decaying social structures of the Old World, as yet unfamiliar with enlightened American democracy and individualism—became easy targets for a wartime society attempting to suppress its own radical element.

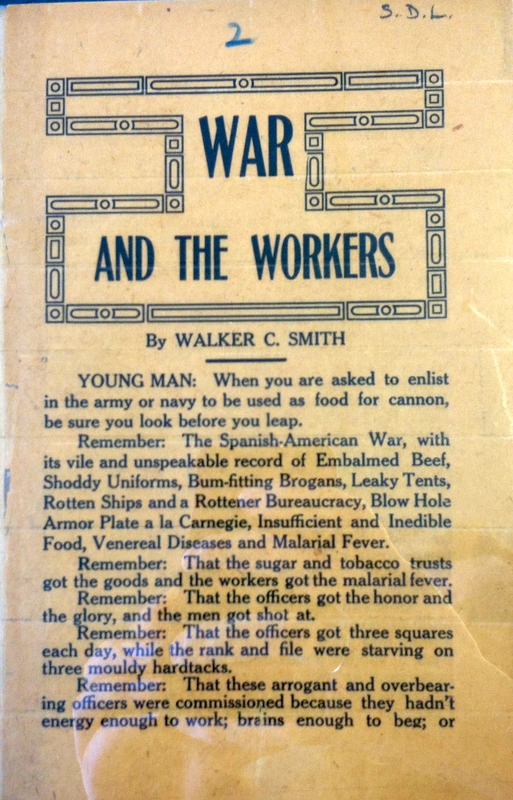

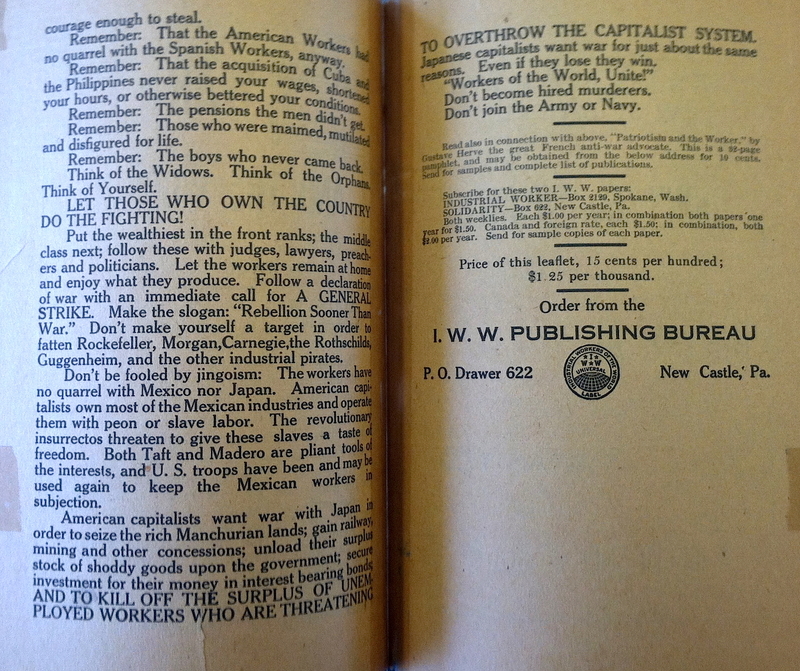

The radical anti-war stance stemmed from the belief that the European war—like all wars besides the workers’ spontaneous revolution—was a capitalist war, whose outcome would only worsen the situation of the workers. Radical organizations urged the working class to remember past conflicts, such as the Spanish-American war, fought for the benefits of the capitalist class against an exploited population. According to their analysis, the average American soldier had more in common with the enemy he fought on the ground than he did with the economic aristocracy back home. When the working classes of different nations fought one another, radicals maintained, the class struggle was disrupted and the ties of class solidarity were dissolved. Some socialists and social democrats on the right of the party rejected this stance, claiming that the destruction of Prussian militarism—itself a clear enemy in the class struggle—was ultimately necessary for the emergence of a single, internationally united proletariat. Nevertheless, organizations such as the IWW and the Socialist Party urged their members, and all workers, to refuse to fight or to support the war effort.

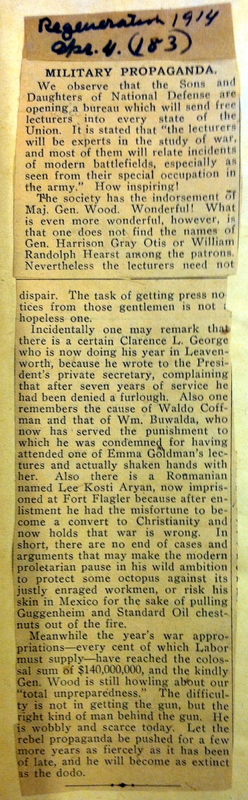

Satirical cartoon from Agnes Inglis' I.W.W. Scrapbook

Rejecting the “dilettante, academic, pink-tea, high-brow” methods of the liberal peace movement, John Haynes Holmes called on the workers to “join forces…with Labor, and strike…at the things which make war—first, militarism; second, political autocracy; and third, commercialism. The axe must be laid at the roots of the tree—which are armaments, dynasties, and exploitation”[3]. In the historical Canton, Ohio speech that earned him longstanding celebration and a ten-year prison sentence, Eugene Debs proclaimed:

The feudal lords, the barons, the economic predecessors of the modern capitalist, they declared all the wars. Who fought the battles? Their miserable serfs. And the serfs had been taught to believe that when their masters declared and waged war upon one another, it was their patriotic duty to fall upon one another, and to cut one another’s throats, to murder one another for the profit and the glory of the plutocrats, the barons, the lords who held them in contempt. And that is war in a nut-shell…And here let me state a fact—and it cannot be repeated too often: the working class who fight all the battles, the working class who make the sacrifices, the working class who shed the blood, the working class who furnish the corpses, the working class have never yet had a voice in declaring war. [4]

Such ideological pronouncements as Debs’ had more immediate, practical motivations than might be initially apparent. Public outcry from not only leftists, but also moderate progressives and average citizens, over the profits industrialists stood to make from the production of war materials gave rise to a critique of war based primarily on doubts about American capitalism. Not only would the “bondholders and stockbrokers” of the country glean millions from American entry into war; without it, they might never recover the large sums they had lent to the British in the previous three years of war. Minority voices in the country pointed to industry’s control of the press, claiming that the former had enlisted news sources throughout the country “in the greatest propaganda that the world has ever known, to manufacture sentiment in favor of war.” George Norris, a Senator from Nebraska, captured public disillusionment in his vehement antiwar speech to the senate on April 4, 1917: “It is now demanded that the American citizens shall be used as insurance policies to guarantee the safe delivery of munitions of war to belligerent nations”[5]. His speech was followed by that of Robert La Follette, whose predictions of an impending social crisis spurred by war were almost cataclysmic:

The poor, sir, who are the ones called upon to rot in the trenches, have no organized power, have no press to voice their will upon this question of peace or war; but, oh, Mr. President, at some time they will be heard. I hope and I believe they will be heard in an orderly and a peaceful way. I think they may be heard from before long[6].

Notes

Please click images for full descriptions and citations

[1] “University Girl Cause of Strike,” Detroit Evening News, December 19, 1916, Box 28, Agnes Inglis Papers, Joseph A. Labadie Collection, University of Michigan Library.

[2] Sisson et al., The American Midwest, 1278.

[3] Scott H. Bennett and Charles F. Howlett, eds., Antiwar Dissent and Peace Activism in World War I America (Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska, 2014), 11.

[4] Stellato, Jesse, ed., American Antiwar Speeches: 1846 To The Present (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2012), 103-4.

[5] Ibid., 87.

[6] Ibid.,92.