Ann Arbor and the Postwar Red Scare

By this point, the antiwar cause had been decimated. Protest, in the form of draft evasion, remained the primary course of action for individuals like Moore. Agnes Inglis and her friends remained staunchly anti-war, but kept to mostly to themselves about it. But while American involvement into the World War signaled the failure of the radical antiwar effort, events on the far side of the conflict gave Inglis, Goldman, and others in Detroit and Ann Arbor renewed hope in the potential of the radical movement, both internationally and at home. It was in celebration of the February Revolution in Russia and subsequent events that Emma Goldman came to Ann Arbor for her last visit in nearly twenty years.

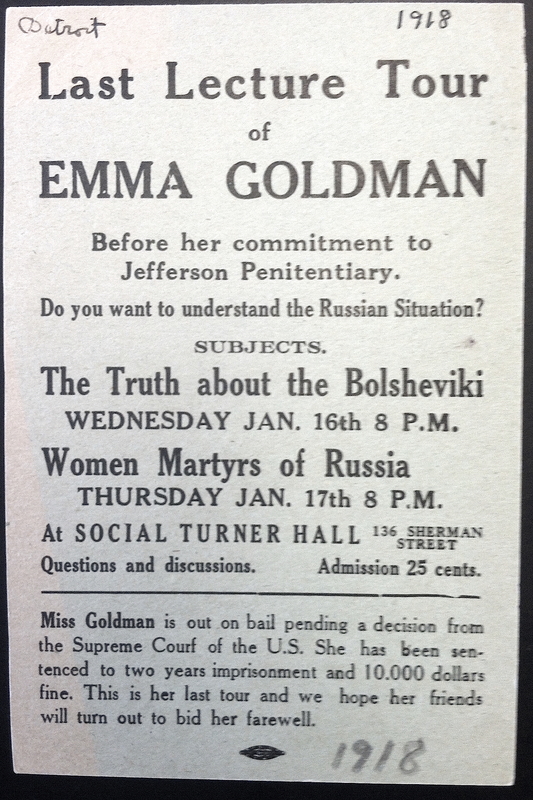

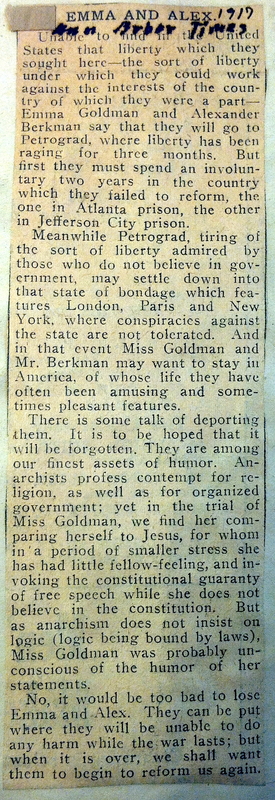

On June 15, 1917, Congress’ Espionage Act went into effect. That same day, the offices of Mother Earth in New York were raided, and Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman arrested. Out on bail the next January, Goldman was able to tour the country one last time before her famous deportation to Russia aboard the Buford. By this point, public sentiment and law were firmly against antiwar and anti-conscription agitation of any sort, as demonstrated in an undated editorial in the Ann Arbor Times. When news of Goldman’s impending arrival and lecture on January 19th reached Ann Arbor, the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) protested, calling for the suppression of her talk. The Detroit Free Press reported that only one woman in attendance protested the move to petition Mayor Wurster. “She insisted she was not in sympathy with Emma or her doctrines, but raised her voice against ‘denying to any one, man or woman, the right of free speech in this city.’” Nevertheless, the vote carried, and the meeting was suppressed by the police.

In Living My Life, Goldman recalled:

In Ann Arbor it was Agnes Inglis, an old friend and a splendid worker, who had made the necessary arrangements for my two lectures. But the noble Daughters of the American Revolution willed it otherwise. Some of those ancient females protested to the mayor, and he, poor soul, happened to be of German parentage. What could he do but carry out the spirit of true American independence? My meetings were suppressed. [1]

In a somewhat more comical manner, Mother Earth recounted:

Indeed, Mayor Wurster’s attempt to shut down Goldman’s visit simply resulted in the relocation of the mass meeting to Inglis’ house. Though the latter was in the hospital at the time, Goldman gave her address on “The Truth About the Bolsheviki,” to the more than one hundred people, mostly University of Michigan students, who crowded into the bungalow. The next day, Detroit Free Press printed an article entitled, “Emma Goldman Eludes Police At Ann Arbor,” while the Michigan Daily reported “Prevent Emma Goldman From Giving Scheduled Address.” Goldman left Ann Arbor, and went to prison. On December 21, 1919, she, Berkman and around 250 others were deported to Russia aboard the Buford.

Notes

Please click images for full descriptions and citations

[1] Emma Goldman, Living My Life, Vol. II (New York: Dover, 1970), 651.