Agnes Inglis: anarchist, activist, and archivist

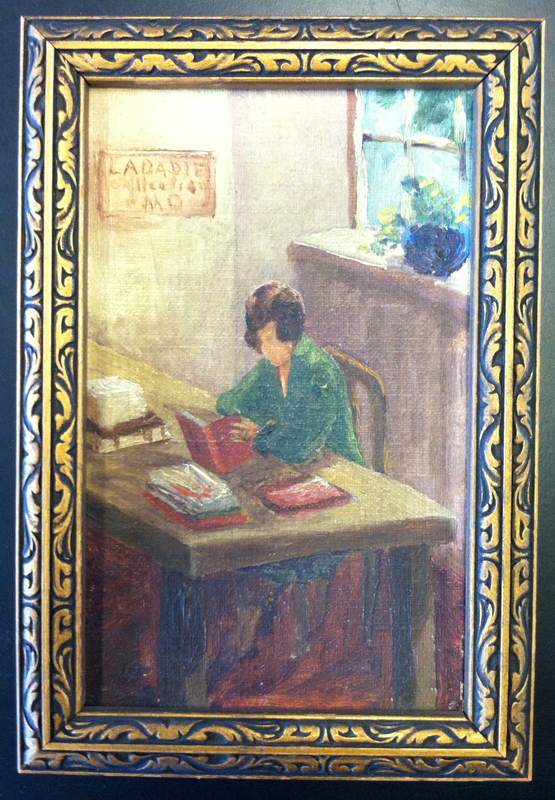

“Ann Arbor, Mich., Dec. 19.—There would have been a strike, probably, but it would have lacked some rather curious phases if a certain earnest little university co-ed hadn’t written a thesis on labor.” Thus read an article from the Detroit Evening News, reprinted in the Detroit Labor News on Friday, December 22, 1916. The strike in question, located at the Hoover Steel Ball plant, was occasioned by a rising disparity between Hoover’s newfound wartime prosperity and the conditions of its workers. That December, “a certain lady of advanced sociological and economic ideas,” having been informed of the workers’ conditions by the aforementioned university student, “got busy among the girls.” This woman—the “evil genius” of the strike, according to General Manager Leander J. Hoover—was Miss Agnes Inglis, Ann Arbor resident, Detroit heiress, friend and confidante of Emma Goldman, and future archivist of the Labadie Collection[1].

Agnes Inglis’ life experience, as narrated in the collection of research notes, personal records and other miscellanea housed at the Labadie collection, provides a key window into the life of the Ann Arbor radical community in the World War I era. At the time of the 1916 Hoover Strike, Inglis had been a confirmed anarchist for some time. Her introduction to the philosophy had come some yearsearlier, in the form of a pamphlet by Emma Goldman titled “What I believe.” Intrigued, Inglis took the opportunity of Goldman’s next visit to Ann Arbor, in March of 1912, to attend her two lectures: “Sex. Its great Element of Creative Work” and “Art and Revolution.” Inglis and Goldman did not meet until the following March, when the latter returned to Ann Arbor and was invited by a shy, yet eager Inglis to have dinner at her home. Goldman accepted, the first step in what would become a productive professional partnership and lifelong friendship. That same spring, Inglis attended her first Detroit I.W.W. meeting with her friend Jessie Phelps, an Ypsilanti schoolteacher. In a small pamphlet entitled “Reminisces,” Inglis recalls:

…Walter asked us if we wanted to go to an I.W.W. meeting. It sounded adventurous and odd, but we said we did…That was my first I.W.W. meeting but not my last. It made a great impression upon me. And when the following year Ford gave “his” workers an eight hr day I knew he had not handed it out to them on a silver platter. I knew in fact, that the I.W.W. or the men themselves had made the decision to work eight hours. What Ford did was to stave off a strike, and accept their ultimatum…The impressive thing was the sober earnestness of these workers, their quiet intelligence, their determination. It was all so simple, so quiet, so impressive. One knew what was said by all on account of what was said in English. It was to the effect that summer was moving on, unemployment would set in, they would lose their jobs, they would go to other places, Flint, Lansing and other automobile places to look for jobs. Never forget, they…admonished, work for the eight hour day!—Work for the eight hour day.

Intense the struggle—1913. Work for the eight hour day. But back of the mechanic is a mgr who cares for a palace to live in, and the machine speeds up![2]

Click here for original text

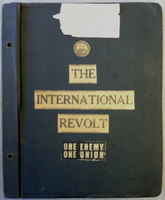

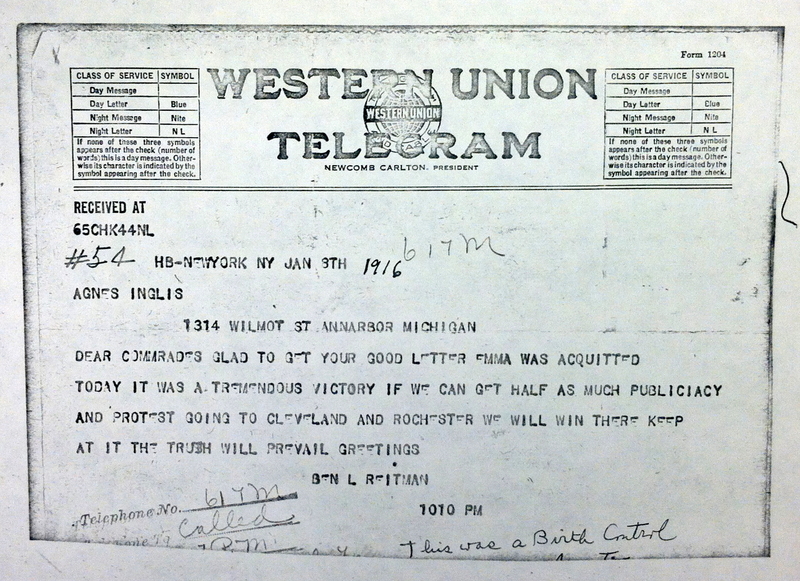

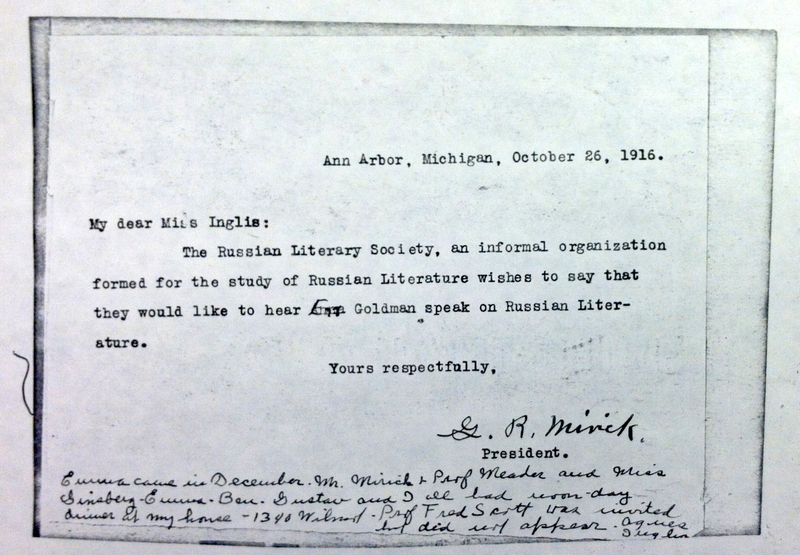

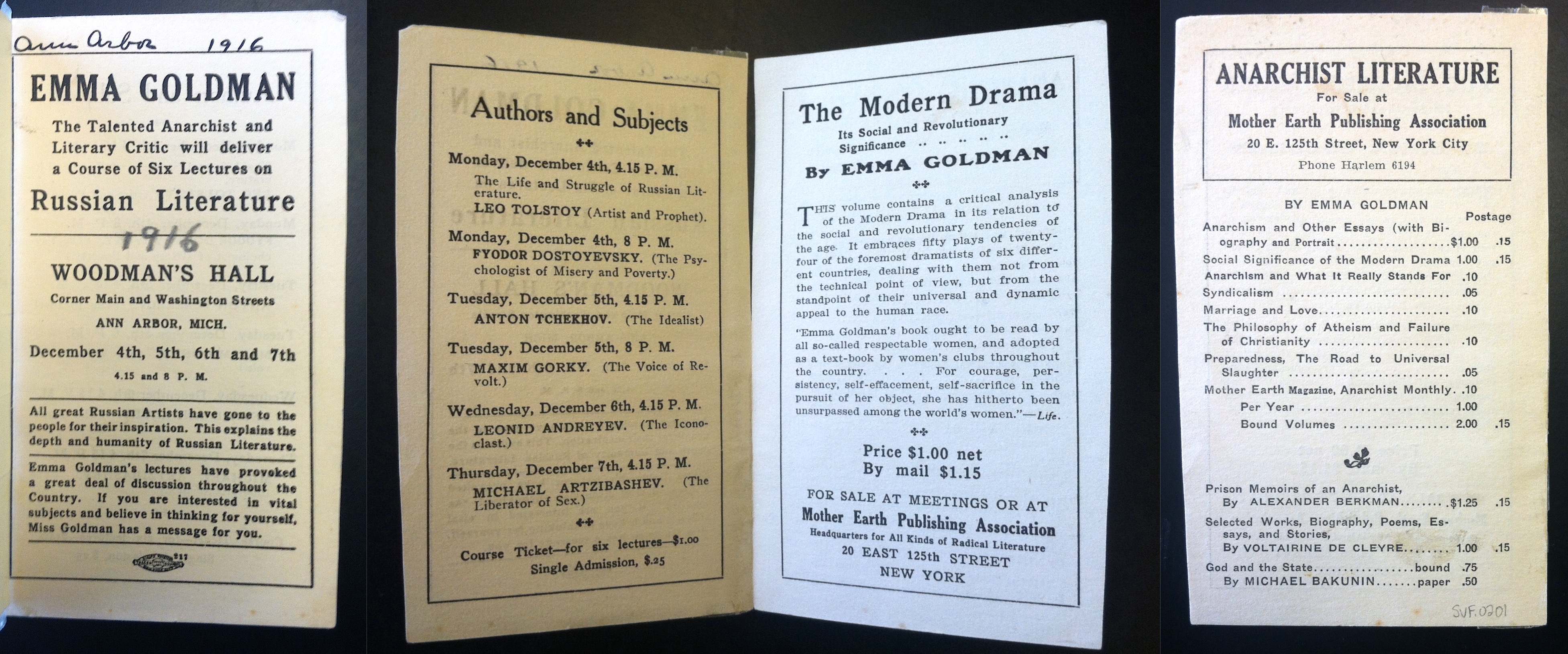

In the years following her revolutionary awakening, Inglis became Ann Arbor’s most important and prominent radical and Emma Goldman’s “Ann Arbor representative” [3]. Goldman had spoken in Ann Arbor every spring since 1910 on topics ranging from syndicalism to Russian literature. In her autobiography and elsewhere, she made note of the crowds of shockingly rowdy and badly-behaved University students that greeted her in Ann Arbor. When Goldman returned in 1915, Inglis organized her lectures on Nietzsche and birth control, then a dangerous, and indeed illegal, topic. The arrival at the latter meeting of the Ann Arbor police did not, according to Inglis, perturb the intrepid Emma—though she would be jailed in New York six months later for her continued efforts to educate the working public on birth control. When Goldman returned to Ann Arbor again, the wholly different focus in her lectures reflected a corresponding shift in public attention—away from anarchism, birth control and the more distant future of American labor, and towards “Preparedness: The Road to Universal Slaughter.”

Pamphlet advertising Emma Goldman's 1916 lecture series in Ann Arbor

Notes

Please click images for full descriptions and citations

[1] “University Girl Cause of Strike,” Detroit Evening News, December 19, 191, Box 28, Agnes Inglis Papers, Joseph A. Labadie Collection, University of Michigan Library.

[2] Agnes Inglis Papers, Box 27, Joseph A. Labadie Collection, University of Michigan Library.

[3] Carlotta R. Anderson, All-American Anarchist: Joseph A. Labadie and the Labor Movement (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1998), 231.