Radical Politics in the World War I Era: The View from Ann Arbor

Paul Blanshard’s undergraduate years at the University of Michigan, as described in his autobiography, were set against the not-so-distant backdrop of a tense and uncertain moment in American history. From a boarding house in sleepy Ann Arbor and the secluded stacks of the University library, Blanshard watched the transformation of his home region’s industrial base and the concurrent rise of the Midwestern movements for socialism and industrial democracy. He writes: “The period of my college life, 1910-1914, was a period of prodigious restlessness in America, and I shared in the restlessness”[1].

To a brilliant, idealistic and reform-minded college senior in 1914, the burgeoning Socialist movement showed immense promise. Relations between labor and capital in turn-of-the-century America had experienced more than two decades of tremendous flux. The conditions of workers worsened with the rise of nationwide industries and the transformation of the industrial workplace, the growth of an unskilled and largely immigrant working class to meet these new demands, and the decline of craft unionism. In the American Midwest, home to the country’s steel, automotive, rubber and coal industries, these transformations were particularly profound.

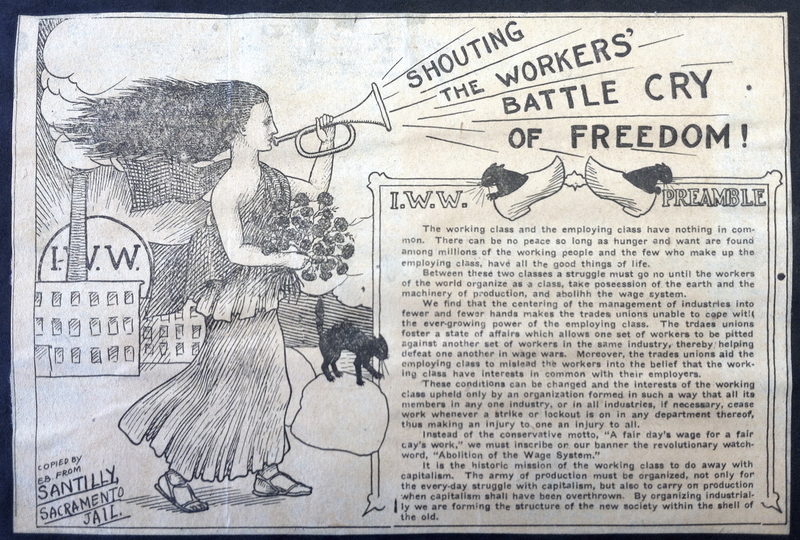

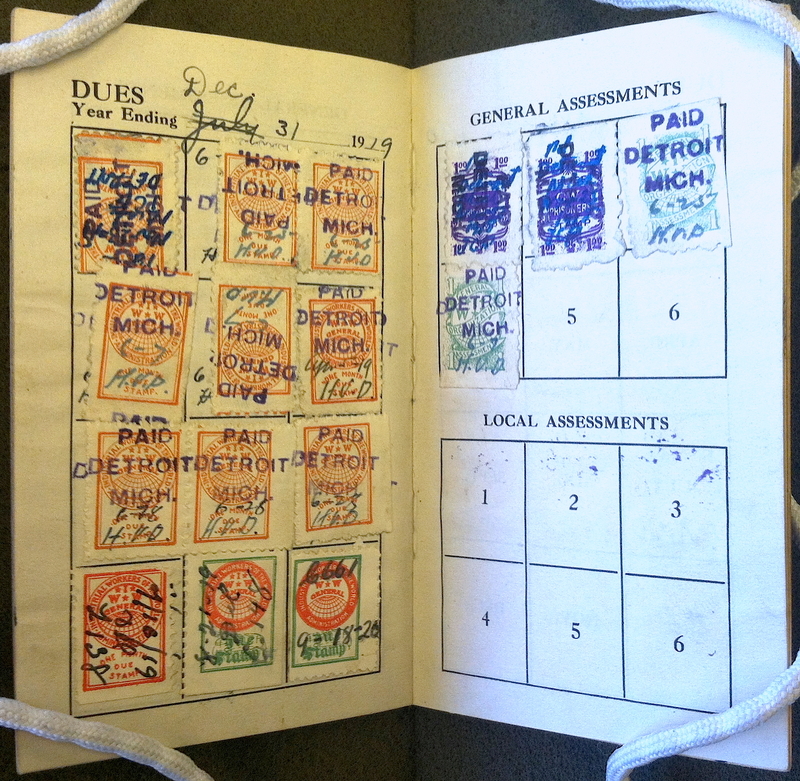

The response to drastic social changes was the rise of the political left, a movement that gained its momentum from a firm and steady stronghold in working-class Midwestern metropolises. In the prewar period, the Socialist Party of America achieved considerable success in grassroots campaigns around the industrial North and Midwest, gaining notable victories at public elections. A few cities, such as Schenectady, New York, Dayton, Ohio, and Milwaukee, Wisconsin, became Socialist strongholds as local Socialists allied themselves with Progressives and appealed to the middle class through reform-oriented agendas. By 1911, 70% of Socialist politicians elected to public office hailed from Midwestern states [2]. Yet mainstream “sewer Socialism” was not the only ideology that developed to meet the challenges of worsening class relations; both Progressivism and militant strains of radicalism also built homes in the Midwest. The former movement hoped to improve the lives of working people from above while maintaining the bourgeois, middle-class American dream; the latter to build a working-class consciousness that would allow American workers to “rise not out of their class but with their class”[3]. In 1905, the International Workers of the World (IWW) was formed in order to advance the prospect of “industrial democracy,” through the creation of “one big union,” all-inclusive and dedicated to promoting the power of labor against management. During the First World War era, this organization and others like it saw membership swell rapidly as the movement for broad union participation regardless of craft allegiance gained ground.

Though firmly middle-class Ann Arbor, Michigan, was no hotbed of metropolitan radicalism, Detroit was. The Detroit labor movement around the turn of the century mirrored that of cities throughout the Midwest. The sizeable influx of European immigrants associated with radical movements in their home countries after the failed European revolutions of the mid-19th century established vibrant Detroit-based networks of Socialism and Anarchism. Detroit was home to the first local chapter of the Knights of Labor (KOL), organized by famous “Gentle Anarchist” Joseph A. Labadie in 1878. This organization was joined by the Detroit Trades Council in 1880, and the Michigan Federation of Labor in 1889 [4]. The Anarchist movement in Detroit was fostered by figures like Labadie and Robert Reitzel, editor of the famous anarchist German-language journal, “Der arme Teufel.” Yet these individuals and their cause remained primarily on the ideological fringe of the leftist movement; it was coalitions of pragmatic Socialists and labor activists who gained more concrete successes in the prewar period.

The transformation of the automotive industry with the innovations of Henry Ford featured a violent and controversial struggle between labor and capital. In 1913, the Detroit I.W.W. led the city’s first major autoworkers’ strike [5]. Faced with rising absenteeism and continued activity among the “Wobblies,” Henry Ford instituted the labor reforms that would garner him international fame: the eight-hour, five-dollar workday. From the point of view of doctrinaire Socialism, Ford’s introduction of a “Sociological Department” giving him unprecedented control over his workers’ lifestyle was unsuitably paternalistic, while his labor reforms failed to alter the basic relationship between workers and the fruits of their labor. Yet Socialists at local and national levels—including John Reed, William Z. Foster, and the Michigan Socialist Party—praised Ford indiscriminately, calling him “industry’s miracle maker,” and a “great thinker, a statesman of industry”[6]. In 1915 and 1916, famous socialists such as Kate Richards O’Hare toured Ford’s factory at Highland Park and proclaimed it a worker’s paradise, “the most spectacular experiment ever made in the world”[7].

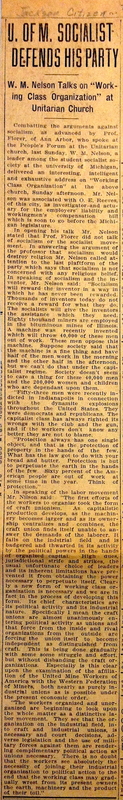

At the University of Michigan, the prewar conversation on Socialism remained primarily academic. Yet this in and of itself demonstrates the significance of the movement. Among the traditional canon of coursework on classical civilization and the great books, courses on Socialism and Anarchism began appearing in the Philosophy and Political Science Departments. In 1911, Professor Robert Mark Wenley of the Philosophy department introduced a course on Anarchism, corresponding with famous Anarchist Emma Goldman in choosing his students’ reading material. Professor Roy Wood Sellars, also of Philosophy, offered a class on Socialism that regularly sponsored guest lectures from Socialist speakers touring the country through the auspices of the New York-based Intercollegiate Socialist Society (ISS). In an interesting twist, members of this society—themselves members of the bourgeoisie by most accounts—were able to invest themselves in a movement that proclaimed to be the charge of the working class. Espousing a suspected and repressed ideology, the members and organizers of the I.S.S. styled themselves as members of the “intellectual proletariat.” As the thinkers and scholars of tomorrow’s society, they maintained, they would have to overcome the forces of the bourgeois academic mainstream in order to accomplish Socialism’s goals of crafting a freer, fairer and more democratic society.

Despite—or perhaps because of—students’ enthusiasm and idealism, academic acceptance of the Socialist movement as a viable area of study had its limits. In 1910, William E. Bohn, an English professor who had earned his doctorate at the University, was “‘eased out of his job’…for spending his weekends giving lectures on socialism in the towns around Ann Arbor”[8]. Paul Blanshard, the developing Socialist, listened to economics professor Fred Taylor “‘demolish’ Marxism in three easy lectures”[9]. And Professor Warren W. Florer of the German department gained attention in the Ann Arbor and Detroit newspapers for his stirring and emphatic denouncements of the Socialist program. Rebuttals of Professor Florer’s polemics from members of the Intercollegiate Socialist Society were published in the Ann Arbor Daily Times-News, making for a rich and lively public debate in the town and at the University.

But for Paul Blanshard and other students with an emerging “socialistic” bent, the forces moving one “towards socialism were outside the textbooks"[10]. Members of the University of Michigan Chapter of the Intercollegiate Socialist Society met in University facilities for regularly scheduled discussions and debates. Prior to 1914, such meetings were lively, exciting and well-attended. The Michigan Chapter was, in the immediate prewar period, one of the organization’s nationwide leaders in terms of membership; so much so, that at the Society’s Fourth Annual Convention in 1912, the delegate from the Michigan chapter was invited to demonstrate his organization’s success in a paper entitled “How to Increase the Membership of the ISS chapters”[11]. The February-March 1913 issue of the Society’s periodical, The Intercollegiate Socialist, remarked: “As usual, the University of Michigan chapter is doing splendid work.” A small article in the national periodical highlighted the chapter’s activities during the year:

Himself a witness to these events, Paul Blanshard recalls: “Down in a dirty little hall in Ann Arbor, I attended a Socialist Party meeting and heard an eloquent speech by a former clergyman, Alexander Irvine.”[12] A Christian socialist like himself, Irvine’s words struck a deep and fundamental chord with Blanshard. So too, the presence of influential labor leaders like Frank Bohn—a University of Michigan alumnus himself, founding member of the I.W.W. and friend of Eugene V. Debs—on a conservative campus indicates the centrality of the debate on Socialism in academic as well as working-class metropolitan circles. Perhaps most suggestive is the fact that non-Socialist faculty members like Professors Reeves and Florer gave the movement enough import to seriously take part in, and associate their names with, debates over its viability. Unquestionably, the national conversation on Socialism in the years leading up to 1914 was coming to occupy a larger and larger place in the public mind.

Notes

Please click images for full descriptions and citations

[1]Paul Blanshard, Personal and Controversial (Boston: Beacon Press, 1973), 23.

[2]Richard Sisson, Christian Zacher, and Andrew Cayton, eds., The American Midwest: An Interpretive Encyclopedia (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University press, 2007), 1253.

[3]Richard W. Judd, Socialist Cities: Municipal Politics and the Grass Roots of American Socialism (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1989), 13.

[4]Sisson et al., The American Midwest, 1287.

[5] Ibid., 1287.

[6] John Reed, “Why they Hate Ford,” Masses, 8 (October 1916); Upton Sinclair, The Flivver King (Chicago, 1984, originally 1937), as cited in David Roediger, “American and Fordism—American Style: Kate Richards O’Hare’s ‘Has Henry Ford Made Good?’” Labor History 29 (1988), 243.

[7] The National Rip-Saw (Jan. 1916), as cited in Roediger, “Americanism and Fordism,” 242.

[8] Constantine, J. Robert, Letters of Eugene V. Debs, Volume 2, 1913-1919 (Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1990), 294n.

[9] Blanshard, Personal and Controversial, 23.

[10] Ibid.,23.

[11] Intercollegiate Socialist Society (U.S.), The Intercollegiate Socialist, Vol. I, No. 1., February-March 1913 (New York: Intercollegiate Socialist Society, 1913).

[12] Blanshard, Personal and Controversial, 24.