The Peculiar Case of Henry Ford

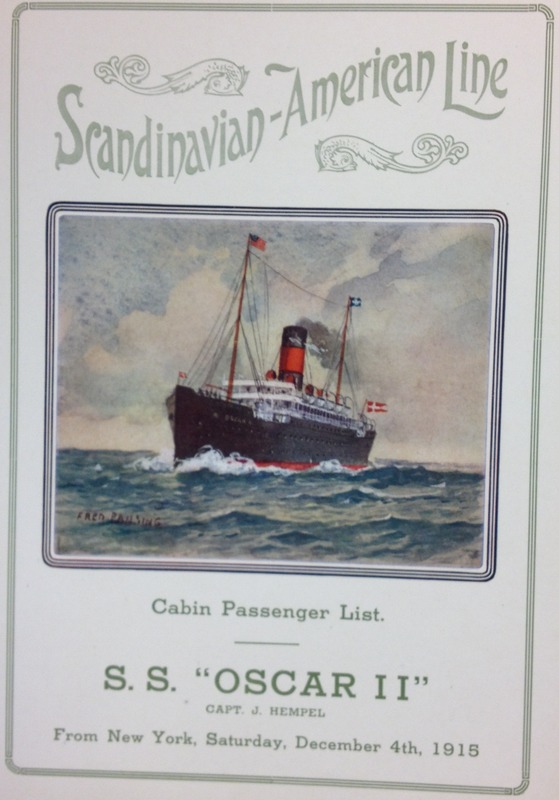

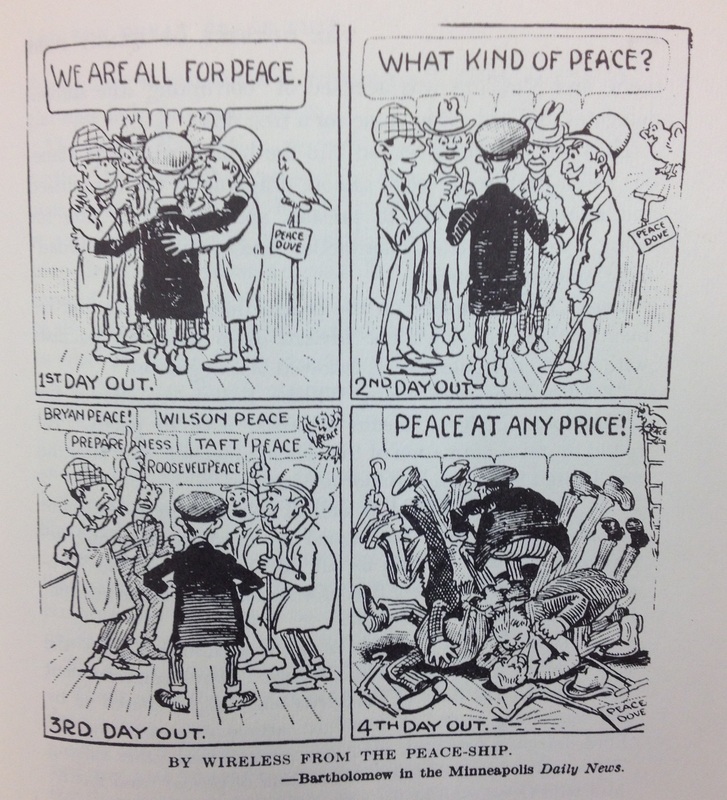

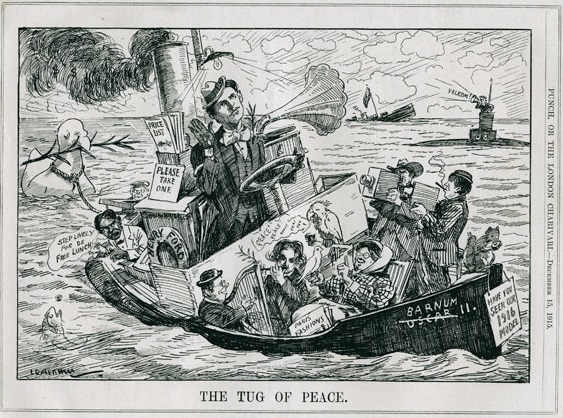

In comparison to the jingoism popular among other Detroit automotive industrialists like Henry B. Joy and Roy D. Chapin, Henry Ford at first appears to be a very peculiar case. Ford, who described himself as a pacifist, was frustrated with the continuing war and the profiteering that came along with it. In the summer of 1915, Ford announced that he would begin a peace campaign to bring an end to the war. This idea, buffeted by his own belief that the war could be stopped by an appeal through the international press in a matter of weeks [1], matured with the help of Rosika Schwimmer and Louis Lochner, two peace activists. Together, Ford, Schwimmer and Lochner developed the Peace Ship expedition. Ford chartered an ocean liner, Oscar II¸ to carry representatives from the United States to meet in Norway with prominent peace activists from other neutral countries. Complications, however, arose rather early in the voyage. Many members of the expedition aboard Oscar II distrusted Schwimmer, fearing her to be a spy for the Central Powers. Henry Ford instructed his bodyguard to spy on the neurotic Schwimmer, which only validated her paranoia [2]. Moreover, arguments broke out among the representatives concerning the conditions for peace, with some favoring disarmament, others favoring a peace under Allied terms, and still others favoring an unconditional ceasefire [3]. Despite Ford’s position as an ideological outlier when compared to other industrialists, he socially profited from his peace expedition, unlike other Detroit industrialists who financially profited from the production of war materiel. Although the peace expedition failed at achieving its stated goal, it can be understood as an economic success for Ford, much to the contradiction of his own convictions.

Not long after landing, Ford, weary from the long trip at sea, chartered a ship to return him home to the United States, leaving the peace expedition behind in Norway. Although he continued to support the expedition morally and financially, the peace activists he left behind quickly fell into disarray. A large fissure had opened in the conference between the camp of Frederick Holt, Ford’s personal representative, and that of Schwimmer, who had assembled a large following [4]. Although the activists did establish a useful instrument in the Neutral Conference for Continuous Mediation, the conference failed to make much headway. One activist complained to Ford that most of the time and money spent in Europe had been wasted, accomplishing nothing [5]. After Holt regained control of the conference in March, the conference met with Denmark’s Secretary of Foreign Affairs, its first formal recognition by a European State [6]. Despite this progress, Holt and his supporters would make little more. Bad press continued to plague the conference, and persevering through it became a challenge in of itself for its members [7]. After a long string of delays and failures, Ford gave up entirely on the project in the spring of 1917.

Ford’s Peace Ship became an object of ridicule in the press, the same press which he believed he could manipulate to end the war. The expedition was lambasted for its lavishness, moving from the Grand Hotel in Oslo to the Grand Hotel in Stockholm. This excessiveness, funded by Ford, only worsened public perceptions of the controversial expedition. The Oscar II became known as The Ship of Fools, and was mocked for its naivety. Ford’s financing of the expedition, which would cease in early 1917, would altogether cost him close to a half-million dollars [8], and produce no serious progress in ending the war. Despite this, Ford did not regret his peace endeavor. His anti-war activities eventually caught up with him in 1916 when he was accused by the Chicago Tribune for being an “anarchist” and an “ignorant idealist.” In response, Ford sued the Tribune, but was harassed in court for his Peace Ship expedition and refused to admit that his efforts were over-idealistic [9]. Yet Ford’s idealism was perhaps not the only factor behind his decision to charter the Peace Ship.

Ford’s motivation for the peace ship expedition remains a topic of dispute for historians. While his convictions concerning war may have been a mere extension of his position as a humanitarian industrialist, the issue may have also been personal, originating in his simple upbringing and his family’s avoidance of military service [10]. However, Ford was also not dissimilar from other industrialists as he conveniently benefitted from the war, albeit in a different way than his competitors. Though he differed in his ideological stance on the war, his views did not conflict with his business sense. Perhaps Ford himself evaluated his motivation behind the Peace Ship best: “Best free advertising I ever got” [11]. Indeed, Ford was not oblivious to the ramifications of his highly publicized venture into Europe. In fact, Lochner concluded that publicity was the only definite part of Ford’s peace plan [12]. Ford’s own comments on the publication of his peace expedition confirm the duality of his motives. “If we had tried to break in cold into the European market after the War, it would have cost us $10,000,000. The Peace Ship cost one-twentieth of that and made Ford a household word all over the continent” [13]. Ford’s peace activism, therefore, seems more in-line with the actions of other prominent Detroit industrialists when it is measured in terms of its economic consequences. Of course, the Peace Ship was an earnest effort by many activists to bring an early end to the war, and in this regard it was a failure. Yet the Peace Ship was also an investment for Ford, which paid off handsomely for him, advertising his benevolent character across America and Europe. After the United States entered the war, Ford would become the largest manufacturer of Liberty Motors for aircraft, defying his earlier stance on the war, and muddling the line between peace activist, patriot, and profiteer.

Notes

Please click images for full descriptions and citations

[1] Barbara S. Kraft, The Peace Ship: Henry Ford's Pacifist Adventure in the First World War (New York: Macmillan, 1978), 55

[2] Burnet Hershey, The Odyssey of Henry Ford and the Great Peace Ship (New York: Taplinger Pub., 1967) 130.

[3] Hershey, The Odyssey of Henry Ford, 102.

[4] Frederick and Lilian Holt Peace Expedition Papers (1915-1917), Box 1, Joseph A. Labadie Collection, University of Michigan.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Hershey, The Odyssey of Henry Ford, 143.

[9] Kraft, The Peace Ship, 280.

[10] Ibid., 50.

[11] Hershey, The Odyssey of Henry Ford, 157.

[12] Kraft, The Peace Ship, 223.

[13] Hershey, The Odyssey of Henry Ford, 157.