The Auto Industry

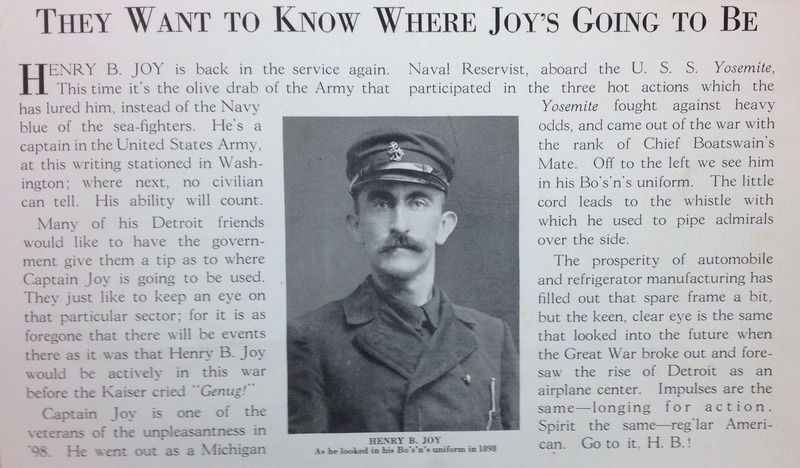

Southeast Michigan’s auto industry, one of the early twentieth century’s most iconic industries, took a leading role in shaping attitudes around the Great War. Many leading members of the auto industry were staunch militarists, such as Henry Bourne Joy of Packard Motors and Roy Dikeman Chapin of Hudson Motors. Joy was a member of the American Defense Society, an even more nationalist and militaristic splinter of the National Security League, and was frustrated at America’s hesitancy in entering the war [1]. Joy’s enthusiasm for American participation in the war even caused him to join the war effort as a Captain in the Army [2]. Chapin, who served on the Council of National Defense’s highway transport committee, advocated the creation of a highway networks throughout the United States that could expedite the mobilization process [3]. Yet regardless of their personal convictions about the war, it made good business sense for automotive industrialists to support America’s entry into the conflict. Cadillac, Hudson, and Packard were already producing ambulance cars for the Allies. Chapin even cooperated with the American Ambulance Corps in France to donate a replacement for a Hudson ambulance that was destroyed at Verdun [4]. Acts of war preparedness by the auto industry brought them great attention and great profits. The only exception to this was Henry Ford, a pacifist who favored American neutrality and actively sought to bring an end to the war through a peace mission. Henry Ford, however, would not have his way. War in 1917 heralded a wave of direct cooperation between the automotive industry and the federal government.

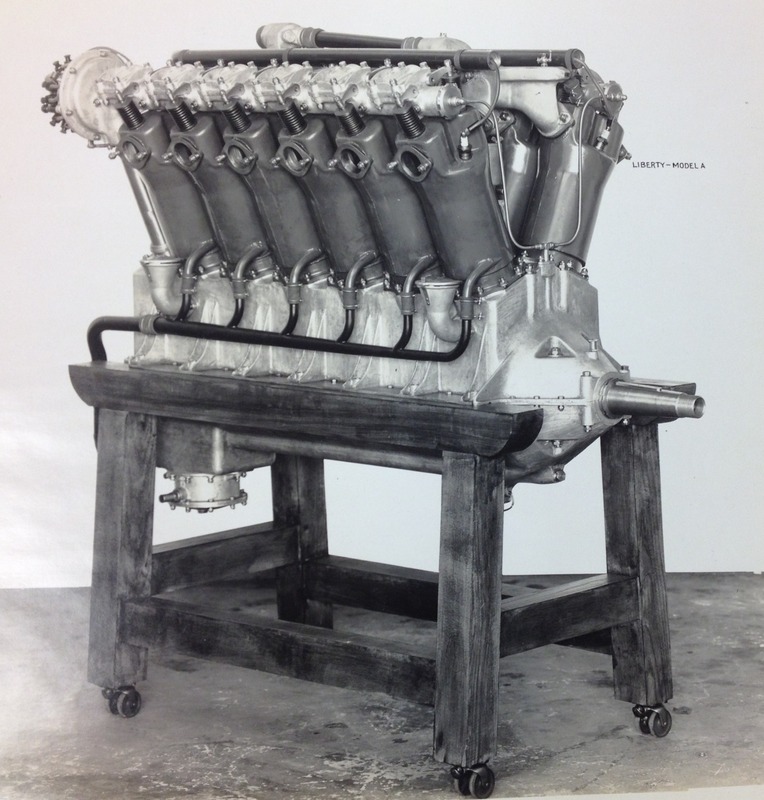

The most popular contribution the automotive industry brought to the war effort was perhaps the Liberty Motor, a powerful and groundbreaking new airplane engine designed to exceed previous speed records while also being extremely lightweight. When Secretary of War Baker announced the Liberty Motor in the summer of 1917, he applauded a group of engineers who convened in Washington to design the engine in a mere five days [5]. In truth, Packard Motors had begun development on the Liberty Motor in the fall of 1914 in preparation for American entry into the war. When the War Department finally called for the development of a standard motor that could compete with European designs, the Liberty Motor was simply adapted to fit federal expectations and was thus ready in five days. Almost immediately, Packard, Cadillac, Lincoln, and Ford began production on Liberty Motors, before any airplane body was ready for the new engine, which meant that engine saw little action in France [6]. Regardless, production of the Liberty Motor became a subject of national pride as the motor quickly became one of America’s most celebrated industrial innovations. Manufacturing the Liberty Motor was also immensely profitable work, with Ford netting around five million dollars from the motor’s production, and Packard even more [7]. The government’s enthusiasm in financing Liberty Motor production was not unique: cooperation between automotive industry executives and the War Department was highly integrated during the war. LINK Several industrialists would use their wealth gained from the war to fund humanitarian efforts at home and abroad, as well as financing the institutions that trained their prospective engineers.

The University of Michigan and its College of Engineering were crucial for the auto industries headquartered in nearby Detroit, as they supplied invaluable engineers and research. Chapin, who attended the University before dropping out to found Hudson Motors, felt a particular allegiance to Michigan. Chapin provided financial support for the Michigan Union project and established a graduate fellowship in his name for advancement of Highway Engineering, an issue that was of particular importance to him as the chair of the Highway Transport Committee of the Council of National Defense [8]. His donations amounted to over $1000 by the end of 1919 fiscal year [9]. Meanwhile, Professor of Engineering Clyde E. Wilson defended the superiority of Bourne’s Liberty Motor in the Michigan Daily, stating that any claims of its inefficiency were no more than exaggerated claims seeking to stir up the public. Wilson, who helped develop the motor’s crankshaft, was another University faculty member with hands in the automotive industry. Detroit industrialists and the University shared a kind of symbiotic relationship, in which the institution’s research for industrial products translated into jobs for the faculty, or even donations and fellowships from the cooperating industries. Automotive industrialists, therefore, used the war to promote their interests inside both the federal government and local public institutions.

Notes

Please click images for full descriptions and citations

[1] Henry Bourne Joy Papers, Box 1, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

[2] Henry Bourne Joy Papers, Box 14, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

[3] Roy Dikeman Chapin Papers, Box 3, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

[4] Roy Dikeman Chapin Papers, Box 4, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

[5] The True Story of the Liberty Motor, (Scientific American 118, no. 22, 1918).

[6] J.G. Vincent, The Liberty Aircraft Engine, (Washington, D.C.: Society of Automotive Engineers, 1919).

[7] Noble Snaples, Institutionalizing Aircraft Procurement in the U.S. Navy, 1919-1925, dissertation (Texas A & M University, Aug., 1999).

[8] Roy Dikeman Chapin Papers, Oversized Volume 2, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

[9] Financial Report of the University of Michigan for the year ended in 1918 (University of Michigan: Ann Arbor, 1918).