Conscientious Objection

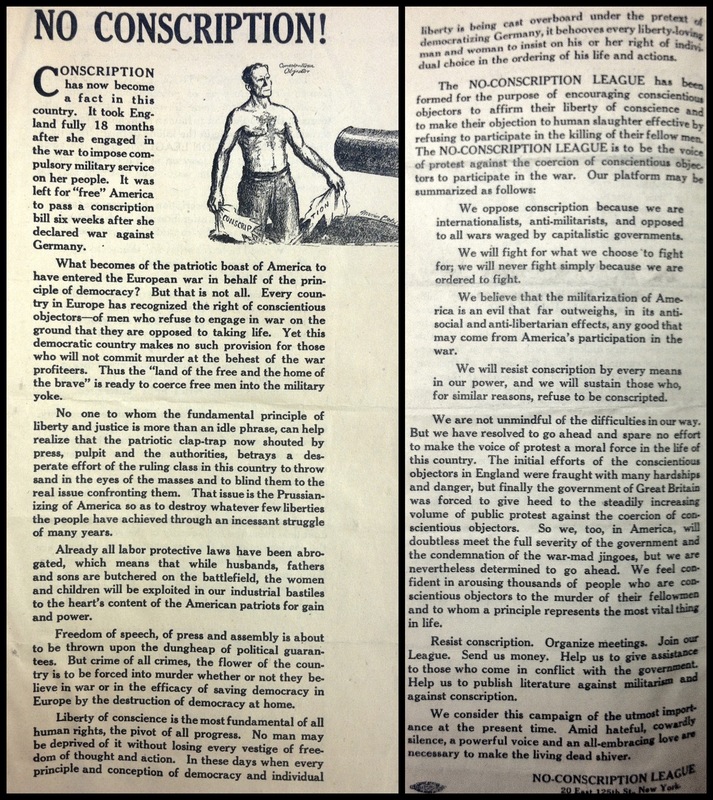

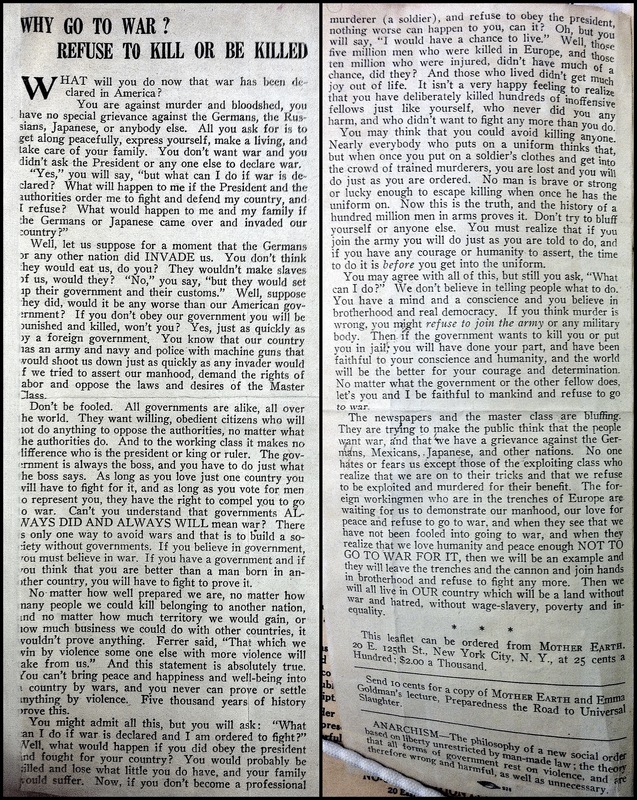

Ellwood’s reason for resisting registration—his own opposition to war and conscription and corresponding moral compulsion to protest both, his aspirations for a patriotism that could “embrace the world,” and his personal obligation to the principles of individual liberty and freedom of conscience—were not unique to him. A small, yet fervent minority opposed to conscription on moral grounds emerged throughout the country and would gain growing national relevance in the trials of conscientious objectors throughout the final months of war and beyond. In Fort Riley, Kansas, where many of the 450 conscientious objectors who maintained their “absolutism” throughout the war wound up, a motley crew of idealistic, young social gospel Protestants, members of historically pacifist religious sects like the Quakers or Molokans, and hard-line radicals were brought together. The first group made up more than 90% of all CO’s—yet in an era where the “Christian socialist” movement was gaining sizable adherents, the first and last categories often fused together. Indeed, many young Christian CO’s interred for their viewpoints experienced radicalization precisely as a result of their time in Camp Funston, Fort Riley. [1]

Harold Gray, a second-year student at Harvard University and native of Detroit imprisoned at Fort Riley, gives a report in one of his letters home of meeting a man who matches Ellwood’s description:

The two evidently arrived at Camp Funston for similar if not identical reasons. Harold, himself opposed to the message of violent revolution espoused by the radical CO’s, would have engaged in engrossing debates with Moore and other socialists over the possibility for a social contract based on an authority other than force, the responsibility of Christians to work for the empowerment of the lower classes, and the degree to which conscription represented the denial of personal individual liberty. During his time in prison, Gray himself was radicalized somewhat, becoming disillusioned with what he perceived as the hypocrisy of the American government in blatantly corrupting the ideals it purported to be enforce. Imprisoning him and others like him, he maintained, published “to the world the fact that religious and political freedom is only a myth in the United States.”[2] In a letter to his family dated August 22, 1918, Gray proclaimed:

If democracy means the right of the majority to stifle truth in the minority I cannot think of a worse fate befalling the world than the coming of democracy. But if democracy means a government of the people by the people and for the people and in which the individual is free to follow the truth as it is revealed to him then I am out for democracy and I intend to fight for such a state with all the power which God has given me.

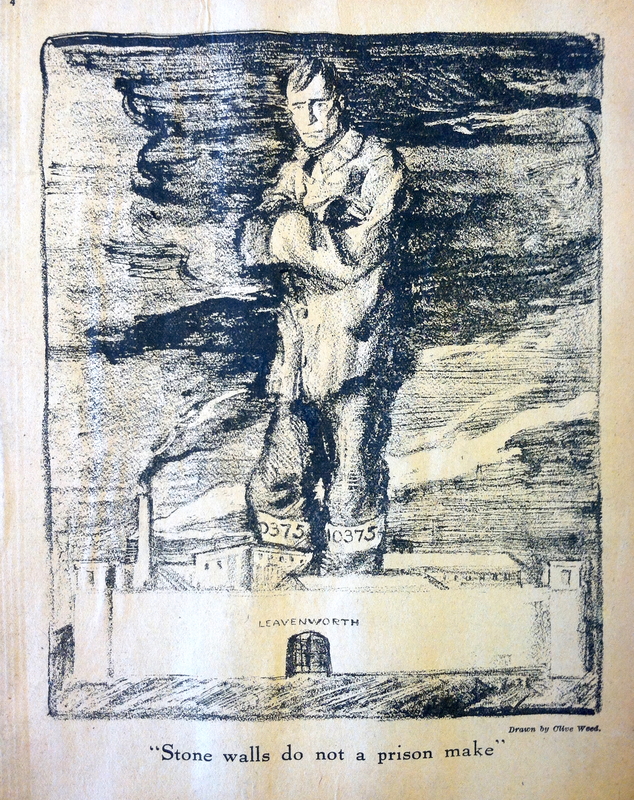

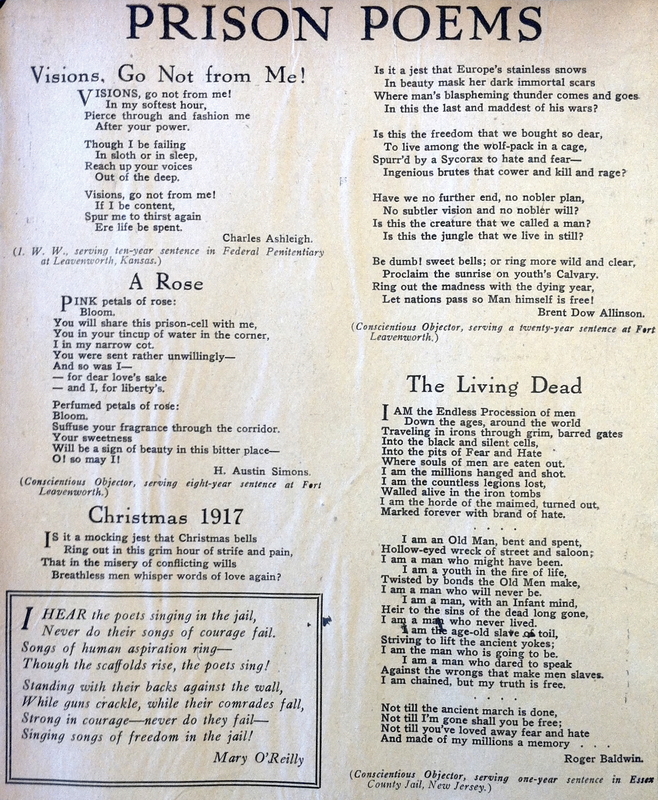

To the radicals opposed to war, conscientious objectors like Frucht, Moore, and Gray represented the height of courage, moral conviction, self-sacrifice and heroism on behalf of a higher cause. They were also the truest patriots, willing to face intense physical hardship and deprivation and harsh sentences, ranging from years in prison to death, for the sake of the ideal—complete freedom of conscience—for which they claimed the country had been founded. Publicly, this small collection of individuals became perhaps the most infamous and widely hated group in the United States, detested for lack of patriotism, cowardliness and failed masculinity. Conscientious objectors faced public hatred and disgust in the newspapers, at their trials, from the military men who served as their guards, and, on occasion, from their own families and friends. Yet radicals—a group almost as hated, and with whom the category of CO certainly overlaps—held them up as the standard of heroism. Reversing the culture of machismo and claim of effeminacy that characterized the national discussion over soldiering and conscientious objection, an I.W.W. slogan claimed: “Don’t be a soldier, Be A Man.”[3]

The CO’s themselves, meanwhile, viewed their actions with great pride. In many cases, the hardships they experienced in prison only increased the ardency of their zeal and fanaticism. In a July 30, 1918 letter home, Harold Gray describes an intense feeling of happiness washing over him as a result of his own faithfulness to his conscience. “I am very, very happy and you haven’t the slightest cause for worry. I feel myself part of a great fight and you have no idea what a wonderful joy that gives one” [4] A few weeks later, another one of Harold’s letters describes the doctor’s surprise at seeing how well he and his friend are holding up under their hunger strike. “I guess if he has ever had dealings with starving men before they have not been men who were starving on (for) principle and needed only to say a word to get plenty to eat. When a man’s spirit is in a job you can’t always calculate how he will act or what he can do or endure” [5]. Perhaps Gray’s most profound and astonishing letter is that written directly after his court-martial, an event for which he had been waiting for months. Locked in solitary confinement, reading and reciting poetry to himself, Gray recalls the process of his court-martial and the experience of hearing the judge recommend a death sentence. He is calm, determined, and firmly convinced of the righteousness of his actions [6].

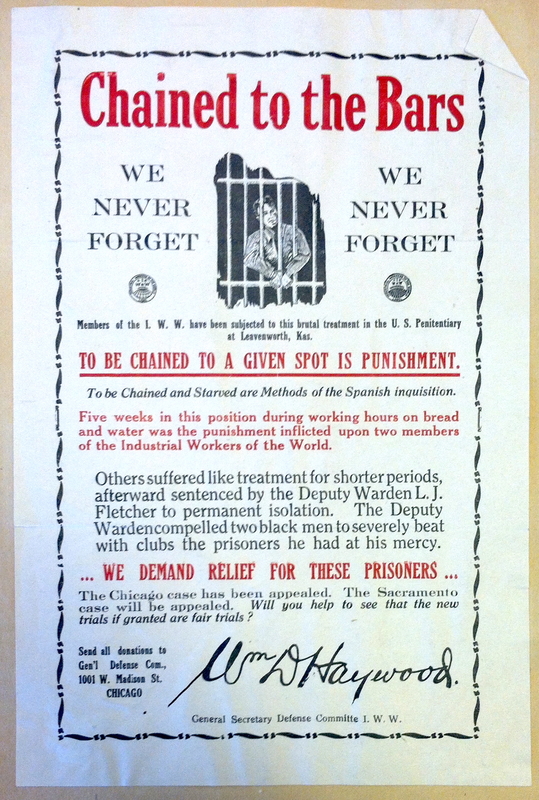

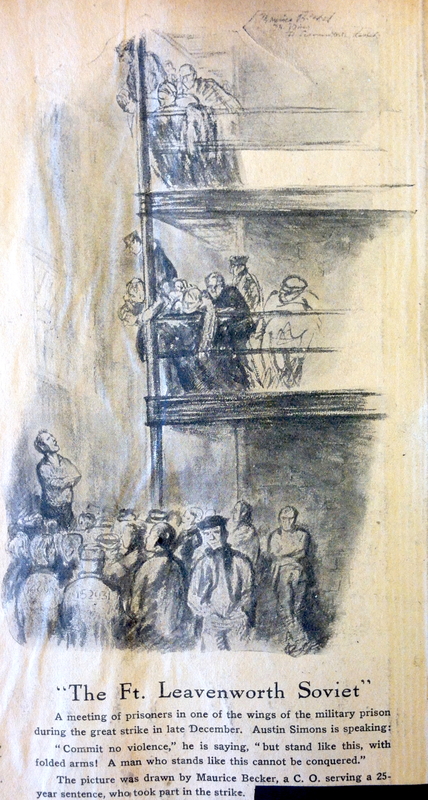

Throughout the country, radicals and peace activists organized massive campaigns to free the imprisoned conscientious objectors, forming organizations such as the Friends of Conscientious Objectors, the Bureau of Legal Advice, the National Civil Liberties Bureau, and the American Union Against Militarism to protest the inhuman treatment of conscientious objectors in prison. Gray and others like him—including Evan Thomas, brother of Norman Thomas—experienced frequent beatings, exposure to cold and rain, cold showers, malnourishment, verbal and physical abuse, and lack of medical treatment when needed. In some cases, they were manacled to the bars of their cells for up to nine hours a day. There were multiple cases of prisoners going insane as a result of neglect [7]. In response, Gray and others initiated a widely publicized hunger strike, for which they were eventually force-fed. Following the the official conclusion of war with the signing of the Treaty of Versailles on June 28, 1919, their pleas increasingly gained ground and attention in Washington and throughout America. By the early 1920’s, most CO’s—including Harold Gray—had had their sentences commuted and were released from prison.

Notes

Please click images for full descriptions and citations

[1]

[2] Letter from Harold Gray dated August 7, 1918, Harold Studley Gray Papers, Box 5, Bentley Historical Library.

[3] Frances H. Early, “Feminist Pacifists and Conscientious Objectors,” in A World Without War: How U.S. Feminists and Pacifists Resisted World War I, Frances H. Early (Syracuse, N.Y.: Syracuse University Press, 1997), 104.

[4] Letter from Harold Gray dated July 30, 1918, Harold Studley Gray Papers, Box 5, Bentley Historical Library.

[5] Letter from Harold Gray dated August 25, 1918, Harold Studley Gray Papers, Box 5, Bentley Historical Library.

[6] Letter from Harold Gray dated September 5, 1918, Harold Studley Gray Papers, Box 5, Bentley Historical Library.

[7] “Report of Treatment of Conscientious Objectors at the Camp Funston Guard House”; “Moans from the Military Machine,” Harold S. Gray Papers, Box 5, Bentley Historical Library.