The American Red Cross and War Relief

(Box 6, Louis H. Fead Papers, Bentley Historical Library)

The American Red Cross (ARC) was one of the most prominent humanitarian relief organizations during the First World War. During the Presidencies of Taft and Wilson, the small American branch of the Red Cross expanded dramatically under the liberal internationalist aims of both administrations. As the ARC was a private organization, it quickly became an avenue through which the United States could provide relief in the international arena without the diplomatic complications tied to official actions of the American government. For example, in December of 1911, Taft declared the ARC to be “the official volunteer aid department of the United States” [1]. However, despite its prominence with politicians and elites in the pre-war period, the American public was “willing to fund specific ARC appeals, but not support it on a permanent basis” [2]. This attitude would change with the outbreak of the Great War in Europe. Though Americans remained reluctant and divided over national involvement in the war, the ARC arrived overseas within months of the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand along with volunteers from across the nation [3]. The ARC began its relief activities in Europe from a position of neutrality, but as the nation’s sympathies shifted so did the organization's efforts, and its humanitarian work soon only benefited the Allies.

Much of what the ARC was able to do abroad emanated from local efforts and sacrifices. At the University of Michigan, for example, the President’s residence (known as “Angell House” for the former University President James Burrill Angell) was converted into a production center dedicated to making bandages and knitted items for use in hospitals overseas. The Michigan Daily made several appeals for increased student participation at Angell House in 1917, decreeing that “every girl is expected to help” by volunteering for shifts that were overseen by the Women’s League. This sacrifice was described in the paper as a “consecration” of their the students’ time, as the college bulletin noted that, “faculty women, and college girls [were] busy there every day, working with the ladies of Ann Arbor in this good cause.” [4] Angell House was open from 2-5 pm every day, and the time spent by the volunteers ensured that they met and surpassed the production quotas set by the ARC [5]. The production of bandages in Angell House was not the only focus Washtenaw County women, however. Many local women’s organizations contributed to the national knitting campaign. The Washtenaw County chapter of the ARC recommended that each woman's dorm or house knit a specific number of sets, each consisting of a “sweater, muffler, wristlets and socks” [6]. The ARC provided free yarn to everyone interested in helping [7].

The University of Michigan Women’s League and the Red Cross

Before the war, the Michigan University Women’s League welcomed new female students, assisted them in finding housing, and organized social events. The organization began its war relief work in November of 1916 [8]. By the end of March 1917, the women had dedicated their room in the Barbour Gym exclusively to Red Cross work [9].

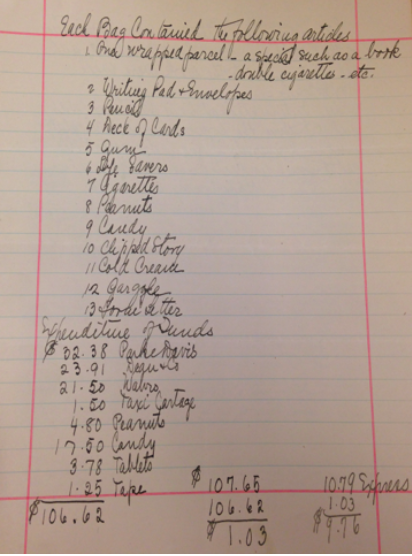

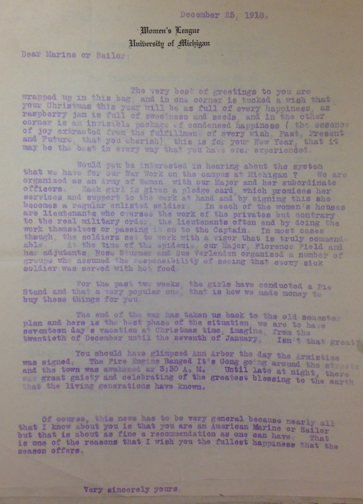

In the winter of 1917, the members of the League committed to complete 100 comfort bags filled with articles “calculated to be useful and pleasing to a soldier at the front, in a hospital, or in a prison camp” [10]. The red, brown or blue poplin bags were then sent to the “American Fund for French Wounded.” The goal was to distribute them at the front around Christmas [11]. Women of the college and townswomen met twice a week to arrange “toothbrushes, chocolates, pipes, soap, towels, and mouth organs” into bags for individual soldiers. In addition to the supplies, the women also placed postcards addressed to some of the contributors into the boxes, hoping soldiers would respond [12]; [13].

In January of 1917, the Women’s League began “bandage and compression work,” contributing to the statewide, multi-organizational effort [14]. The women of the League met every week on Tuesday at 3 pm and by March had cut and folded about 150 dozen surgical compresses to be shipped to the American Ambulance Hospital in Paris [15]. The League women too knitted wristlets, sweaters, and socks for the Michigan contingents of the federal naval militia. The money for the work either came from the treasury of the Women’s League or donations sent in by women from Ann Arbor and women on campus. The materials were bought at local stores.

Membership and Fundraising

The ARC experienced significant growth during the First World War, partially as the result of national and local membership drives. Washtenaw County became the only county in Michigan to have two chartered chapters of the ARC. Both Ann Arbor and Ypsilanti women established a chapter in 1917. Other Michigan chapters were located in Detroit, Grosse Isle, Monroe and Bay City[16].

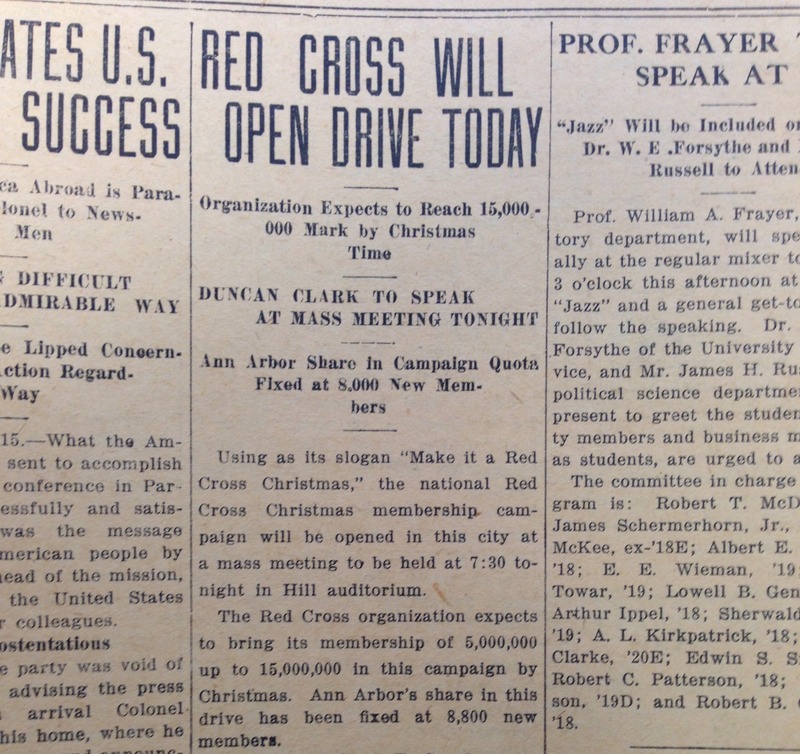

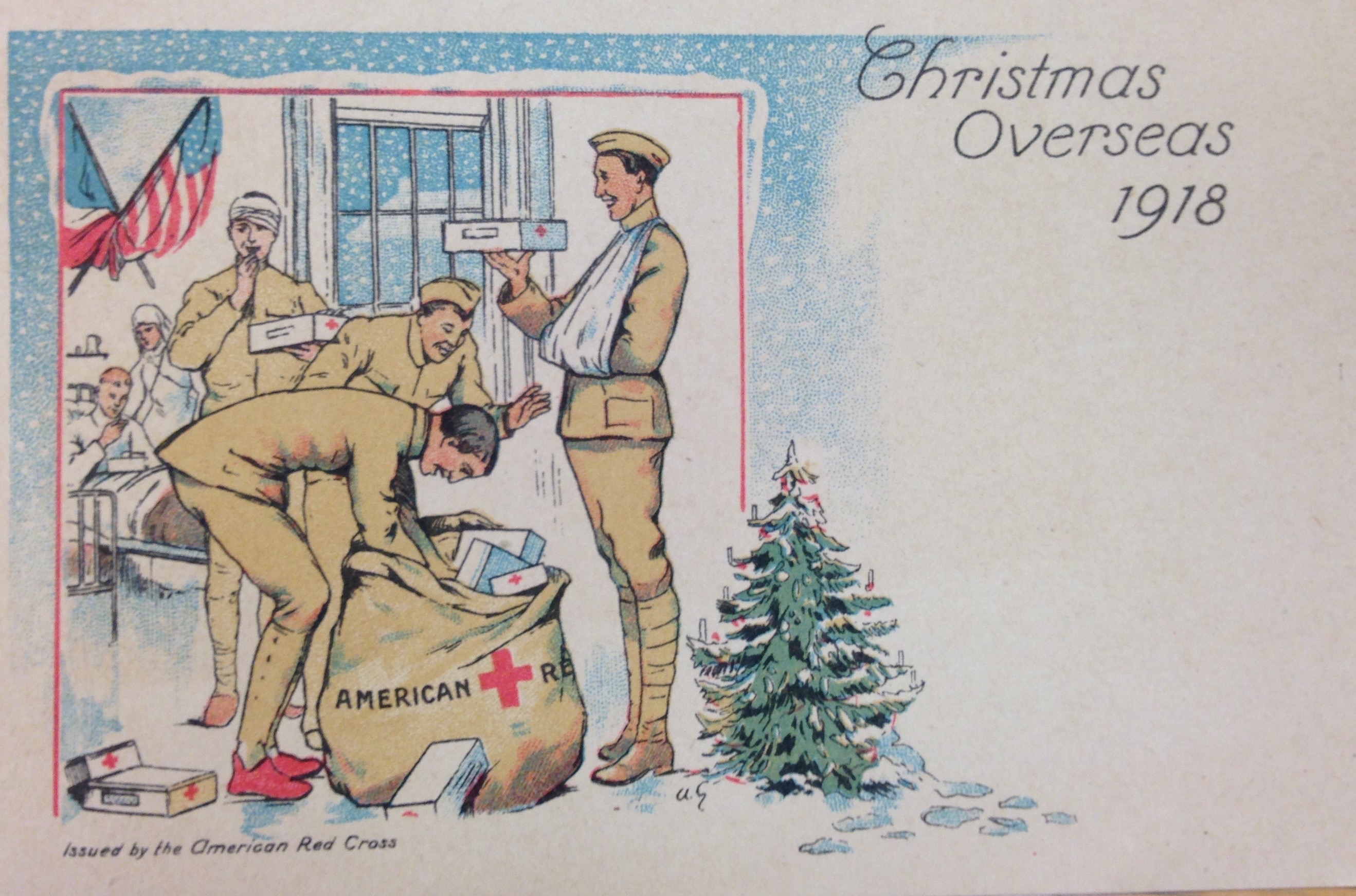

One of the most successful local drives was the National Christmas Membership drive of 1917. The Michigan Daily advertised the campaign widely, framing the contributions to ARC to be a patriotic duty. The appeals in urged wives, daughters, and sons to donate whatever time or money they had. The idea was to provide the fighting men with “the moral support which comes from big membership, all working together in harmony toward one end” [17]. The ARC’s work, the papers announced, was “the work of humanity.” Washtenaw County boys, the ARC declared, "are going to need its ministrations in blood-stained Franc e; since friend or foe is welcome to its care, let us all get behind it and add our names to its rolls” [18]

Another example of Ann Arbor's support for the ARC was the Red Cross parade of held in early May 1918. Set as the opening event for the May 20-May 27 fundraising drive, the ceremony united most local organizations in Ann Arbor [19]. The common goal was to collect $30,000 for the ARC from Washtenaw County. The city government ordered businesses and schools closed, and the university canceled all exercises after 2 pm. The army mechanics, the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (R.O.T.C.), and the university marching band participated, and students walked in their caps and gowns. The parade itself stretched two miles in length. The papers lauded it as “one of the greatest demonstrations Ann Arbor has ever seen” [20]. President McKenny of the Ypsilanti Normal College gave a patriotic address praising the event “not because of its beauty, but because it typifies the grim determination of the people of Ann Arbor, Washtenaw County, and the United States [21]." To further collect funds, the local chapter of the ARC set up five booths on campus in the days following the parade. Though service in the booths was technically voluntary, the papers insisted that it was “every girl’s patriotic duty to aid in the work.” Those who donated “in accordance with his or her means” were rewarded a customary Red Cross button and a voluntary contributor card to be displayed proudly in house windows [22]. In the days following the “voluntary” period of the drive, canvassers continued their work approaching all homes not showing a “V” card in their windows [23]. One Michigan Daily article warned “every home that does not display a V card will be entered, and satisfactory reasons must be presented for a failure to subscribe [24]." The fundraiser was an absolute success. The slogan of the campaign became “Fill the Flag,” and the Michigan Daily reported that the committee had received “buckets of money” in both large and small donations [25]. All money raised from the parade and the resulting drive was then sent directly overseas to the Red Cross Headquarters in Europe [26].

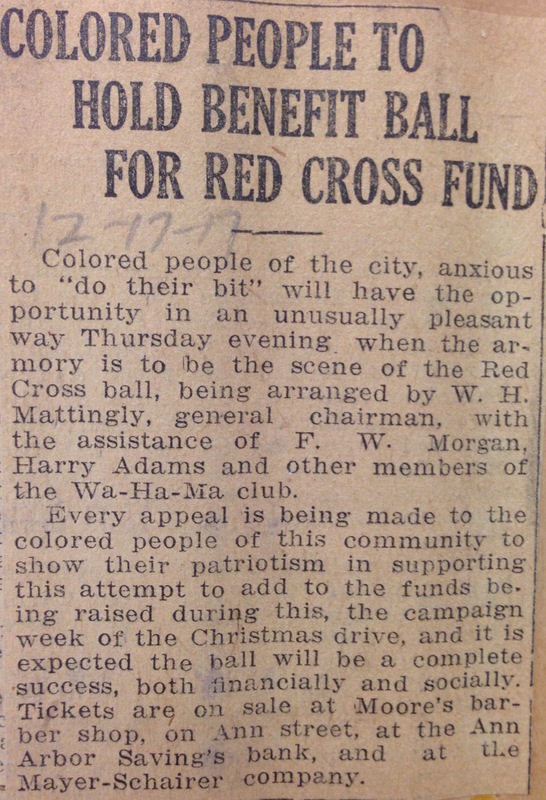

In December of 1917, the “Colored people of the city, anxious to ‘do their bit’” hosted a Red Cross ball at the armory to bolster the Christmas membership drive [27]. The Ann Arbor Daily Times editor expected the ball to be a complete success, both financially and socially [28]. Generally large events, such as the Christmas Membership drive and the Red Cross Parade, were advertised as communal efforts, meant to“sink all our individual differences and personal desires that stand in the way of a united America and the men in the trenches." Although, we found only a single reference to the small African American community in town, it seems that this did not apply uniformly [29]. In contrast to the many articles and photos found recording the Red Cross Parade, the lack of information on the community's participation in fundraising efforts highlights the marginal position of the African Americans in Ann Arbor. This marginalization, of course, stands in contrast to the disproportionate number of African-American men who served in the American Army. Overall, there is little reporting and few archival materials about the Ann Arbor and University of Michigan African-American community of the time; a gaping lacuna we hope inspires future research.

In an interesting twist of history, membership in the ARC was advertised as voluntary despite serious social repercussions for failing to volunteer independently. During the 1917 Christmas Drive, for example, many churches canceled evening services to “give the people of all churches as well as all citizens a clear opportunity to unite in this patriotic gathering.” When two churches refused to participate and held their evening services, the local newspapers attacked them for being unpatriotic. Church officials responded the next day, reminding the Ann Arbor population that not canceling services for the cause was not necessarily unpatriotic. Instead, they argued it was more important to keep the “word of God alive in the minds and hearts of men” than to spend time with “‘talks of war’ on behalf of the Red Cross [30]." Public shaming like this was not uncommon. Overall, the number of ARC chapters jumped from 107 nationally in 1914 to 3,864 in 1918. Membership grew from 17,000 members to over 20 million adult and 11 million Junior Red Cross members. Over the course of the war, the American public would donate $400 million dollars worth of funding and material to the ARC [31].

The wartime activities of the ARC had a lasting impact on American children. As the United States began shifting its political focus outwards at the turn of the century, the Junior Red Cross (JRC) advocated for a program that introduced students to different cultures. Moreover, the goal was to involve children and youth in the organization’s volunteer programs. And by the end of the war JRC branches had multiplied, and teachers organized educational sessions to educate children about the world through lectures and pen pal initiatives. The ARC advocated that “good citizenship meant more than unyielding, patriotic devotion to the United States,” and that being a good American citizen also “demanded being a good world citizen” [32] In 1918, the President of the University of Michigan, Harry B. Hutchins, was appointed as a member of the JRC advisory committee for the state of Michigan. Others appointed to this committee included religious leaders, college presidents, and judges, indicating the importance of the JRC to the state of Michigan.

Notes

Please click images for full descriptions and citations

[1] Julia Irwin, Making the World Safe: the American Red Cross And a Nation's Humanitarian Awakening (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013), 47.

[2] Ibid., 49.

[3] Ibid., 59.

[4] University of Michigan, 1918-1919(Ann Arbor: The University, 1918).

[5] The Michigan Daily, October 9, 1917.

[6] The Michigan Daily, October 23, 1917.

[7] Caroline Bartlett Crane, A History of the Work of the Women’s Committee (Michigan Division) Council of National Defense ( )

[8] Meeting Minutes, November 17, 1916; Minutes of the Women’s League (1916-1917), Michigan University, Women’s League, Box 2, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

[9] Meeting Minutes, March 27, 1917; Minutes of the Women’s League (1916-1917), Michigan University, Women’s League, Box 2, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

[10] Elizabeth Hall, “Report of the Social Service Committee,” Minutes of the Women’s League (1916-1917), Michigan University, Women’s League, Box 2, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

[11] Meeting Minutes, January 20, 1917; Minutes of the Women’s League (1916-1917), Michigan University, Women’s League, Box 2, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

[12] The Michigan Daily, November 26, 1916.

[13] Letter accompanying comfort bags Michigan University, Women’s League, (1916-1917), Box 2, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

[14] Meeting Minutes, January 20, 1917; Minutes of the Women’s League (1916-1917), Michigan University, Women’s League, Box 2, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

[15]Meeting Minutes, March 17, 1917; Minutes of the Women’s League (1916-1917), Michigan University, Women’s League, Box 2, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

[16] Tapping, T. Hawley. ''History of the Washtenaw County American Red Cross."American National Red Cross, Washtenaw County Chapter Records 1916-1976. Bentley Historical Library, Ann Arbor. 9.

[17] Michigan Daily News Clipping in Bassett Scrapbook, Box 1, Ray E. Bassett Collection, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

[18] Michigan Daily News Clipping in Bassett Scrapbook, Box 1, Ray E. Bassett Collection, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

[19] The Michigan Daily, May 14, 1918.

[20] The Michigan Daily, May 22, 1918.

[21] The Michigan Daily, May 22, 1918.

[22] The Michigan Daily, May 18, 1918

[23] The Michigan Daily, May 18, 1918.

[24] The Michigan Daily, May 23, 1918.

[25] The Michigan Daily, May 23, 1918.

[26] The Michigan Daily, May 17, 1918.

[27] The Michigan Daily, December 14, 1917, Box 1, Ray E. Bassett Collection, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

[28] The Michigan Daily, December 14, 1917, Box 1, Ray E. Bassett Collection, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

[29] The Michigan Daily, May 22, 1918.

[30] Ann Arbor Daily Times, December 14, 1917.

[31] “Our History,” American Red Cross. Accessed June 26, 2015. http://www.redcross.org/about-us/history

[32] Julia F. Irwin, “Teaching “Americanism with a World Perspective”: The Junior Red Cross in U.S. Schools from 1917 to the 1920s,” in History of Education Quarterly 53 (2013), 31.