Liberty Loans

To fund its own American Expeditionary Force while simultaneously upholding the economies of Britain and France, each of which had become increasingly dependent on American loans, Secretary of the Treasury William Gibbs McAdoo called for a $2 billion loan, dubbed the Liberty Loan. The first Liberty Loan bonds had a long maturity of 30 years along with a low interest rate of 3.5%, two factors that made the bonds less than competitive with municipal bonds. McAdoo feared that competitive rates could force the dumping of private securities to buy war bonds, which would only destabilize the economy that he was trying to maintain. By keeping interest rates low, McAdoo hoped that the bonds would have a minimal long-term effect on the economy and would be purchased as a form of savings. Most economists and historians agree that the first Liberty Loan was designed to attract lenders who would lower their consumption to purchase war bonds, as opposed to siphoning funds away from other investments [1][2]. Reduced consumption, it was thought, might curb inflation and the rising prices caused by the war. At the same time, McAdoo hoped that the bonds would lessen the burden of the war on the American middle-class, yet he also made interest on the first Liberty Bonds tax exempt, a measure that would only help the upper-class profit from the purchase bonds. Furthermore, increasing excise taxes on items like tobacco and alcohol only made it less likely for lower-class citizens to afford the purchase of bonds. Furthermore, McAdoo and Wilson’s choice to fund at least half of the war’s cost through loans is hardly consistent with their history as progressives. Understanding the Liberty Loans through an economic point of view is therefore both difficult and perhaps less useful than analyzing them as a form of war propaganda.

Although the Liberty Loans had mixed success in achieving their economic goals, they certainly raised public enthusiasm and fervor for the war. Hugh Rockoff, an economist, suggests that perhaps the main purpose of the Liberty Loan’s design was to raise national commitment for the war through the oversubscription of bonds [3]. In fact, to many Americans the sale and marketing of Liberty Bonds became nothing less than an obsession. Failure to achieve oversubscription in some counties was no less discouraging than a massive defeat on the battlefield, a thought that McAdoo reflected upon in his memoirs [4]. To prevent this, McAdoo himself participated in a nationwide tour promoting the sale of war bonds. One national bank lost its charter when the Comptroller of Currency learned that its applicants had bought less than $200 of bonds [5]. Moreover, the government set up war savings certificates, cheap bonds that sold for no more than $4.12. These were marketed towards the young and poor in an effort to include everyone in the war bond craze. The frenzy that surrounded Liberty Bonds was nothing less than hysterical.

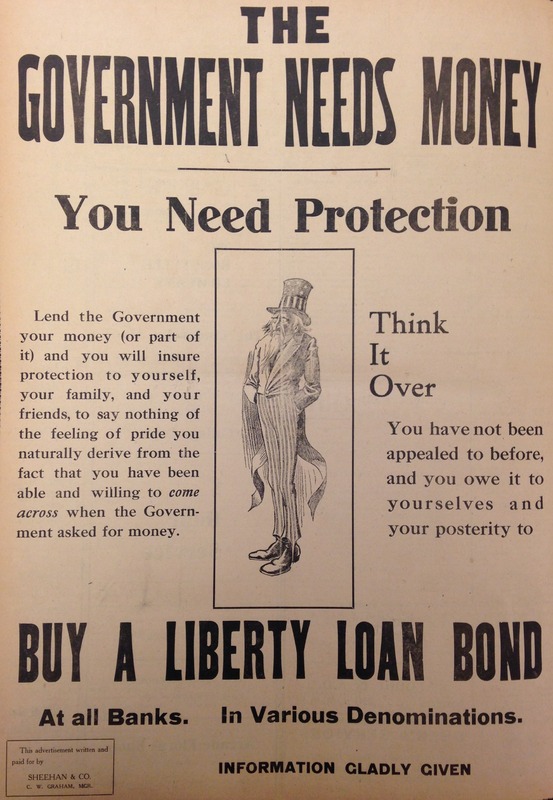

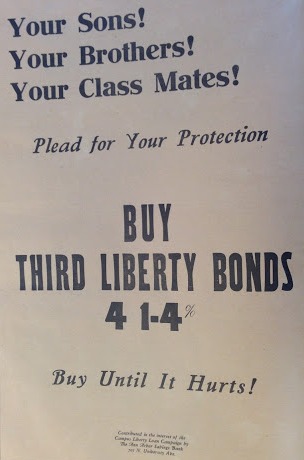

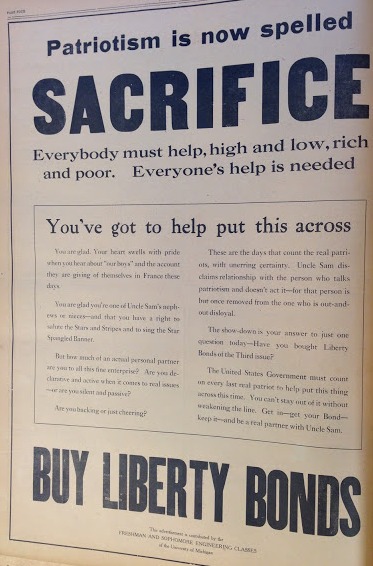

At the University of Michigan, “bond hysteria” dominated the headlines of TheMichigan Daily and the wallets of students. Headlines and bond ads encouraged students to “buy until it hurts” [6], and that “patriotism is now spelled sacrifice” [7]. The University of Michigan was given a quota of $200,000 for the second Liberty Loan by the Ann Arbor Loan Committee, translating to a rate of almost one bond for every student enrolled. Faculty and boosters participating in a 24 hour bond drive adopted the slogan “A bond for every student” [8]. One student’s suggestion in particular reflects the atmosphere on campus:

"If a girl can dance ten miles or so an evening, she can at least walk home half a mile and save the taxi fare to buy a liberty loan bond. The parties that Ann Arbor is notorious for can be cut to buy bonds. Michigan students have spirit and will show it" [9].

Statements such as these illustrate how attitudes towards Liberty Bonds were often ignorant of the economic aspects of the bonds themselves. Students could care less about each bond’s coupon, tax exemption status, or time before maturity. Bonds were not bought as financial investments, they were bought as a patriotic duty.

Many famous Michiganders became important promoters of war bonds, associating their purchase with national pride. In fact, such pride was evident in the first bond purchase in southeast Michigan. Michigan alumni and bond booster Fred Lawton recalled Sam Crawford, a celebrated slugger for the Detroit Tigers, buying a war bond with a rolled-up wad of cash he had been saving for the event.

"It was really a dramatic act, and when I stood up and announced it, a roar of shouting applause greeted Sam, the like of which he had never heard on the ball field after one of his mighty over-the-fence home runs" [10].

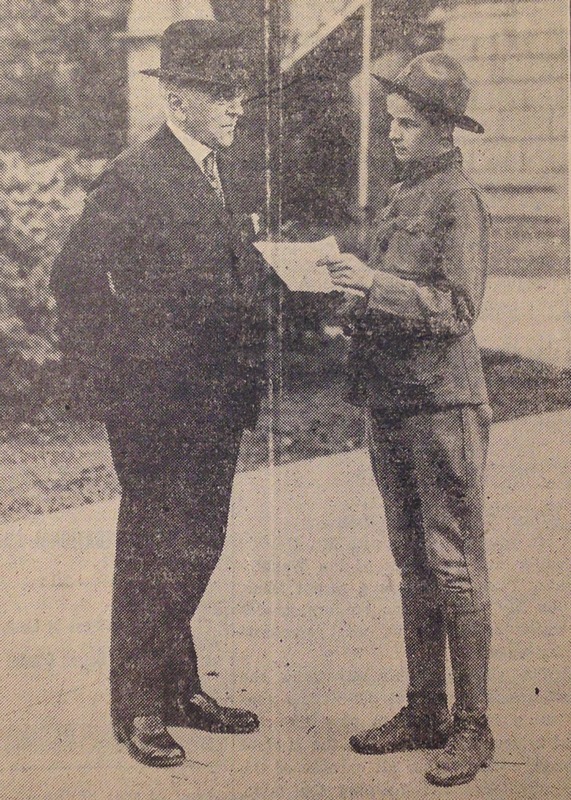

Louis Carlisle Walker, one of Muskegon’s most powerful bankers, made the securing of war bonds for local citizens a priority. Walker kept a close correspondence with bankers in Chicago discussing the sale of Liberty Bonds and was asked to write an article encouraging their sale by the Treasury Department’s Liberty Loan Executive Committee [11]. The University of Michigan’s President Hutchins bought a Liberty Bond from a boy scout, and a photo of the event appeared in TheMichigan Daily the following day [12]. For famous local and national persons, bond buying was more than just a patriotic duty, it was necessary to the integrity of their public image. If pride and patriotism became associated with the purchase of bonds, shame and treason became associated with a failure to purchase them.

While most headlines concerning Liberty Bonds promoted their sale and celebrated patriotic Americans, other articles reprimanded Americans who had yet to buy bonds as un-patriotic. Those who had failed to buy bonds were just as bad as draft dodgers and “loafers,” who were already considered to be unwelcome in America [13]. Ann Arbor’s large German-American population, whom already become a popular target for hazing activities, were especially ridiculed for their failure to purchase war bonds. In fact, one article in The Michigan Daily found it necessary to discourage the use of tarring and feathering as an effective means of curing German-Americans from their lack of patriotism [14]. One farmer in Bad Axe was tarred and feathered for berating bond solicitors [15]. At some times, no amount of bond purchasing seemed to be enough. Even when Michigan students were buying massive amounts of bonds, some faculty members feared that the University would fail to meet its quota, with one headline in the student newspaper speculating that the University was doomed to fail [16]. However, the University proceeded to oversubscribe its quota by $42,000 only ten days later [17].

The way in which local leaders and the government went about marketing Liberty Bonds suggests that oversubscription was an intended goal. Every Liberty Loan was considerably oversubscribed, and Detroit was famous for “going over the top,” or massively oversubscribing. At the University of Michigan, students were presented the honor of raising the “Loan Honor Flag” if they succeeded in oversubscribing the loan quota [18]. It was far more surprising and newsworthy for a county to undersubscribe than to oversubscribe, and by the end of the war, it had become an expectation that citizens would buy more bonds than were available. The culture of patriotic service propagated by the Liberty Loans may have been just as helpful to the government as the loans themselves, as it encouraged citizens to take an active part in supporting the war effort. Therefore, Liberty Loans should be understood as much as a means to promote the war and garner support for it as well as a means to fund it.

Notes

Please click images for full descriptions and citations

[1] David Kennedy, Over Here: The First World War and American Society (New York: Oxford University Press, 1980), 101.

[2] Hugh Rockoff, "Until It's Over, over There: The US Economy in World War I," in The Economics of World War I, edited by Stephen Broadberry and Mark Harrison (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), 326.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid., 322.

[6] The Michigan Daily, April 16, 1918. Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

[7] The Michigan Daily, April 21, 1918.

[8] The Michigan Daily, October 11, 1917.

[9] The Michigan Daily, October 13, 1917.

[10] James Frederick Lawton Papers, Box 2, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

[11] Louis C. Walker Papers, Box 5, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

[12] The Michigan Daily, October 14, 1917.

[13] IThe Michigan Daily, May, 1918.

[14] IThe Michigan Daily, April 21, 1918.

[15] “3 MORE COUNTIES TOP LOAN QUOTAS," Detroit Free Press, April 24, 1918.

[16] The Michigan Daily, October 16, 1918.

[17] The Michigan Daily, October 23, 1917.

[18] The Michigan Daily, May 3, 1918.