A Focus on Food

In 1917, citizens of Washtenaw County united with a collective focus on economic food use, preservation, and growth. To contribute to the war effort, communities recruited everyone -adult and child alike-to tend gardens with the goal of increasing supplies and freeing up food on the market. Many men who remained on the home front volunteered to assist local farmers to counteract the labor loss from enlistment in the military.

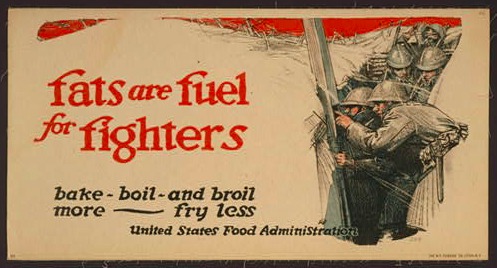

Food became an important part of the culture of the Michigan home front, as well as nation-wide. With the passage of the Lever Food Control Act in 1917, Woodrow Wilson created the United States Food Administration, which had the power to control food and fuel ”with the object of feeding Americans, their armies abroad, and their Allies.”[2] The newly-founded United States Food Administration run by Herbert Hoover led a targeted campaign to encourage nationwide food conservation efforts under the slogan “Food Will Win the War” [3].

The Food Administration encouraged American housewives, students, and business owners to reduce the amount of scarce resources, such as sugar and butter in their meals. It distributed posters reminding everyone of the sacrifice of American soldiers, showed films at local theaters, and encouraged communities to organize “meatless” and “wheatless” days and local gardening. Americans were encouraged to “economize with worthy purpose,” and their efforts became an integral part of the national home front culture. [4]

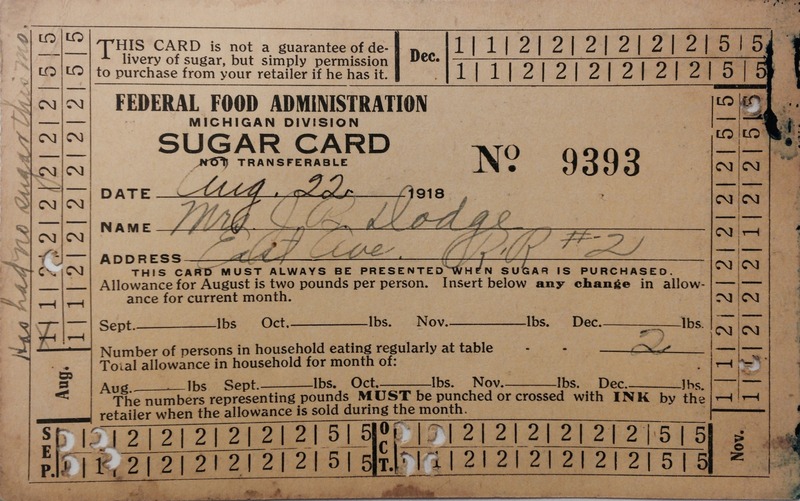

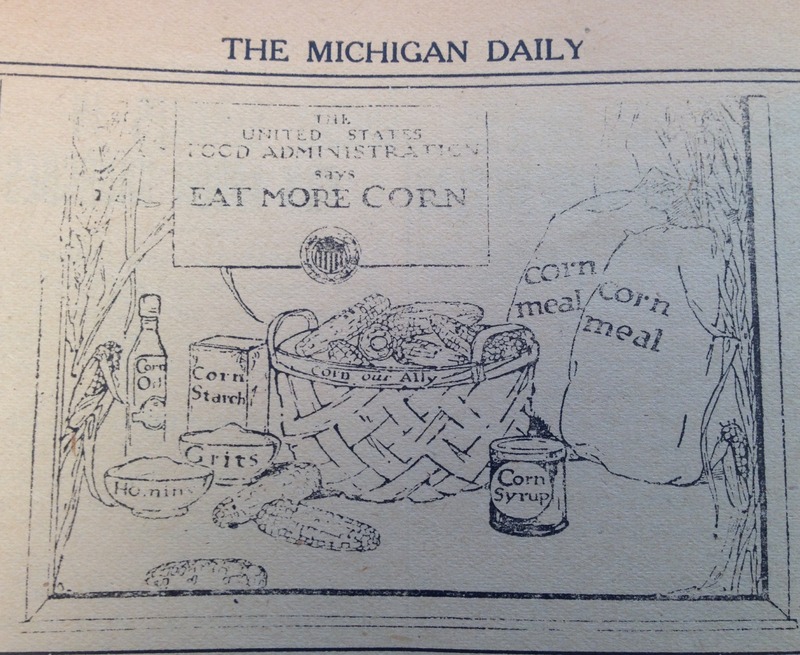

National programs of food conservation and preservation almost immediately were taken up by local communities, Ann Arbor and Washtenaw county included. The University of Michigan was the first college to launch a food conservation campaign and functioned as a test case for the future moves of the food administration [5]. In Ann Arbor, food economy was taught in schools and at the University after Hoover and the Food Administration requested public schools incorporate the science of food economy into their curriculum. To comply with this directive, the University circulated information every month in a newsletter to students with instructions on how best to contribute to the food conservation efforts [6]. The University Bulletin for the 1918-1919 school year noted that courses were offered in food conservation, with over one hundred female participants [7]. Junior and Senior women earned two to three hours of credit in both lecture and laboratory classes focused on food use and nutrition in wartime. The Michigan Daily was a vocal mouthpiece for these efforts as numerous articles were printed on the subject, asking students to “waste nothing” and reduce their use of resources such as wheat, sugar, and meat [8]. Lodging houses, fraternities, sororities, and Ann Arbor restaurants picked up on the food consciousness movement and practiced deliberate meatless and wheatless days to preserve food for those fighting abroad. The reduction of luxurious commodities was also advocated by the Food Administration, as students worked to conserve sugar as well. Volunteers participated in numerous canvasses of homes with Hoover Food Pledge and window cards to reinforce the community’s dedication to the war effort. The first neighborhood canvass took place in the last week of July in 1917. The children of Washtenaw County contributed to a second one by distributing food pledge cards to both their own homes as well as to their neighbors.

The Michigan Daily advertised Meatless and Wheatless days on campus and significant numbers of students pledged to the cause. The locally organized days of abstention came in response to materials circulated by the United States Food Administration. The government agency had claimed that approximately 75,000,000 pounds of meat and meat products needed to be sent to the United States Army and the Allies every week, implying that conservation efforts were urgent [9]. Moreover, the Food Administration encouraged the use of graham, rye, corn, and potatoes as substitutes for wheat, as in the spring of 1918 Hoover asked that the nation “abstain from wheat entirely until the next harvest” [10].

In 1917, local concern grew over the collection, preservation, and distribution of seed potatoes in Michigan and across the United States. The potato, as a supplement for wheat, became an important part of the food conservation campaign. In Ann Arbor, “Potato coupons” were circulated and citizens were invited to pledge “as a patriotic act, not to eat or serve any potatoes, until the spring crop has been planted.” This would ensure there would be enough potatoes for the next year. Those with pecks of potatoes remaining were encouraged to sell them to the Chairman of the Women’s Committee for Public Service, so they could be preserved for planting in the spring. The following spring, the committee sold the seed potatoes to persons who pledged to plant and faithfully cultivate them, with resources also allocated to those who could not afford to buy them [11]. The Women’s Committee was rather serious about the potato effort, to the extent that one woman declared that “she had come to feel that to “eat a potato now would be like eating a Belgian baby!” [12]. The potato movement was so pervasive nationally that a song titled “the Patriotic Potato” was circulated, signifying the importance placed on conservation of wheat both locally and nationally [13].

War Gardens

In addition the Women’s Committee placed a great emphasis “upon the necessity for each family to raise sufficient food to be stored, canned, dried, or otherwise preserved to carry through the year” [14]. During the summer of 1917, “special stress was placed upon Food and Marketing and Food Conservation.” Women volunteers taught eager pupils economic methods in cooking and preservation [15]. More than 25 canning demonstrations were held throughout Washtenaw County [16]. The committee encouraged everyone to maintain their own gardens and to “make use of every good piece of ground.” Those unable to tend to their own lands were asked to loan it to others who would make the effort in their stead [17]. Many property owners offered up empty lots for the cause with the promise that the land would be returned to them after the war. As a result of these efforts, the acorage under cultivation in the State of Michigan during the summer of 1917 was increased by nearly one third [18].

By March 24th, 1918, the Ann Arbor city forester claimed that the national war garden movement had raised $350,000,000 worth of vegetables, indicating the substantial impact that food cultivation movement had on the national scene [19]. The national success was cited to continuously encourage local and regional participation in the effort. Governor Albert Sleeper designated Friday May 3rd, 1918 as Arbor and Garden Day, to encourage Michiganders to plant and maintain their garden for the day. “If you can’t plant a big garden, try a little one; and take care of it. Our soldiers in France must be fed, as must the armies of our Allies, and every pound of vegetables raised in a Michigan garden will release so much wheat to be sent abroad.” [20]

Youth Gardens

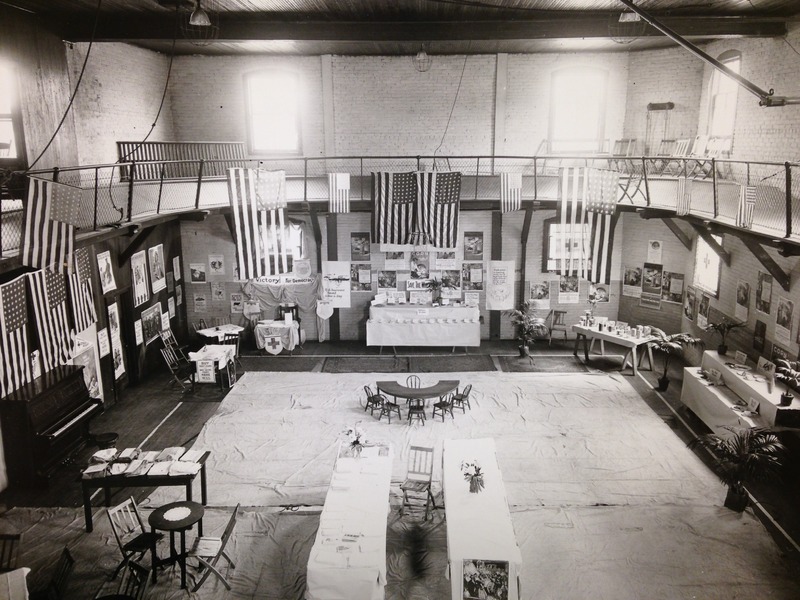

The youth of Washtenaw County was actively engaged in the war gardens movement. Thousands of children tended to their own gardens, encouraged by a special ‘I am Pledged’ button of which 100,000 were sold or given away to those participating [21]. There were four large gardens in Ann Arbor dedicated to youth gardening, located in West Park, Catherine Street, Washington Street, and Burns Park. The acreage could accommodate 500 children in each garden [22]. The children worked throughout the summer and their efforts gained the praise of Mary Markley, head of the Woman's Committee in Ann Arbor: "When grown ups were complaining of the devastation being wrought in their war gardens where the hose could not reach, the children in the school gardens toiled faithfully at dry-farming and worked wonders.” [20]. Most of the results of the children’s gardens were canned at home, while prized products from school gardens were exhibited in store windows in Ann Arbor [23].

In celebration of enthusiastic youth effort, exhibitions of locally grown fruits and vegetables were hosted across Ann Arbor, displaying the “fine specimens” to the community. Burns Park had a large exhibit, featuring the production of 80 children working on 98 gardens [24]. Three different elementary schools worked in this park - Tappan, Perry, and Eberbach- each school designating student officers, with leadership positions of captain, first, and second lieutenant in charge of each school’s contribution. Each garden also had official badges for the students, distributed from the Interior Department in Washington, and the appointed “officers” each had additional insignia of their rank. The exhibit displayed a number of vegetables, namely beets, carrots, cabbages, parsley, potatoes, turnips, tomatoes, radishes, squash, peppers, cucumbers and sugar beets. The exhibit also displayed a homemade American Flag, constructed of a sheet, dyed and hand sewn by four children of the garden [25].

Relief for Farmers

With men registering for the military, farms faced a shortage of manpower during the war years. The press reported that approximately 5,000 farm workers in Michigan alone had left to join the military. To avert economic collapse of farmers, the United States Food Administration encouraged men on the home front to volunteer on farmlands. In line with the University’s overall pro-war sentiments, joining the volunteers on the land was advertised as a worthwhile contribution to the war effort. For example, on Thursday April 19, 1917, The Michigan Daily’s night editor wrote an article, which asked the Daily’s readership to join “a highly effective service for your country back on the farm.” The author, J.L. Stadeker, reminded his peers that “working in the grain fields is far less inviting to most men than fighting on the fields of battle, but nevertheless it is equally honorable, and highly essential. Stadeker followed this with an impassioned statement: “It may offer no chance of honor and glory, it will probably write no names in history, but after all, most of the world’s real and greatest heroes have passed on, unpraised and unsung” [26]. Male students, even if they could not dedicate an entire summer, added their names to an emergency list promising to work for about a week during harvest season to relieve the farmers. University of Michigan professors too helped raise the crop acreage of Washtenaw County by enlisting as laborers to help till the soil. In addition, the Ann Arbor Civic Association (AACA) organized to provide unskilled but willing workers “who will work for a small rate and with public spiritedness to help our government in the time of war” [27]. Acting as a clearing house between volunteers and local farmers, the AACA coordinated volunteers to increase the food supply of Ann Arbor [28]. The University administration even added a program granting credits to students who left school to work on farms [29].

Though male volunteers with previous farm experience were preferred, individuals with no experience were also accepted to meet the demand. Moreover, many women, officially part of the “Women’s Land Army of America” but soon known as “farmerettes,” volunteered to work on farms. This was not uncontroversial and many questioned the ability of women to keep a farm running. The farmerettes volunteered with enthusiasm and were allowed to form their own units, usually consisting of between eight and seventy girls. They worked at least eight hours per day, were reportedly paid the same amount as the male volunteers, earning about $15 dollars a month after all expenses were paid [30]. The work was varied, as women were employed in different types of farmwork: in Traverse City assisting with the cherry crop, organizing children’s gardens in Detroit, and on local farms working in the fields. Other women assisted farmer’s wives by preparing meals, working in dairy farms, and other work necessary for farm upkeep.

In addition to the students and women volunteers, the state of Michigan also mobilized its youth. Despite the fact that many farmers wanted grown men to aid them the whole year or to find tenant farmers willing to work past the summer, an organization called the Boys’ Working Reserve searched for youth volunteers between the ages of 16 and 21 to do summer farm work [31]. “If the war is to be won at home, it must be done through the efforts of boys under the age of 21… in fighting fallows of the fields at home, as their older brothers are fighting in the trenches of Belgium and France,” declared the assistant national director of the Boys’ Working reserve in a call to action posted in the Michigan Daily. [32] Forty high school boys volunteered from the Ann Arbor high school. They were placed in farms as close to their home as possible, though they worked both in Washtenaw and its neighboring counties.

The food conservation efforts of the University of Michigan and the people of Ann Arbor, albeit temporary, were a significant aspect of the home front culture during World War I. But war gardens and farm relief work ended after the war. Ann Arborites turned gardens back into parks, drafted men returned home to the fields, white bread reappeared in meals, and the “Patriotic potato” song was left to history. Still, the practice of wartime communal food preservation and production reappeared as food shortages became a national issue once again during World War II.

Notes

Please click images for full descriptions and citations

[1] The Michigan Daily, March 30, 1918.

[2] David Burner, Herbert Hoover, a Public Life (New York: Knopf, 1978), 100.

[3] ibid. 102.

[4] The Michigan Daily, March 23, 1918

[5] The Michigan Daily, October 10, 1917

[6] University of Michigan Bulletin, 1918-1919 (Ann Arbor: The University, 1918)

[7] The Michigan Daily, October 27, 1917

[8] The Michigan Daily, May 4, 1918

[9] The Michigan Daily, March 31, 1918

[10] Mary Markley. Report of Washtenaw County Women's Committee C.N.D. Council of National Defense, Women's Committee, Michigan Division Records, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

[11] Caroline Bartlett Crane, History of the work of the Women's Committee (Michigan Division), Council of National Defense during the World War (s.n. 1922), 33

[12] Burner, Herbert Hoover, a Public Life, 100

[13] Crane, A History of the Women's Committee, 34.

[14] The Michigan Daily, April 23, 1918

[15] Markley, Report of Washtenaw County Women's Committee C.N.D.

[16] ibid.

[17] Roy C. Vandercook, "Michigan in the Great War," Michigan History Magazine, 2 (1918):261, accessed July 21, 2015.

[18] Newspaper Clipping, March 24, 1918, Ray E Bassett Scrapbook, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

[19] The Michigan Daily, May 4, 1918

[20] Markley, Report of Washtenaw County Women's Committee C.N.D.

[21] Ann Arbor Daily Times, March 24, 1918

[22] Newspaper Clipping, August, 21, 1918, Ray E Bassett Scrapbook, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

[23] Markley, Report of Washtenaw County Women's Committee C.N.D.

[24] Newspaper Clipping, August, 21, 1918, Ray E Bassett Scrapbook, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

[25] ibid.

[26] The Michigan Daily, April 19, 1917

[27] The Michigan Daily, April 18, 1917

[28] The Michigan Daily, April 20, 1917

[29] The Michigan Daily, April 18, 1917

[30] The Michigan Daily May 7, 1918

[31] The Michigan Daily, April 19, 1918

[32] The Michigan Daily, March 30, 1918