War Industry

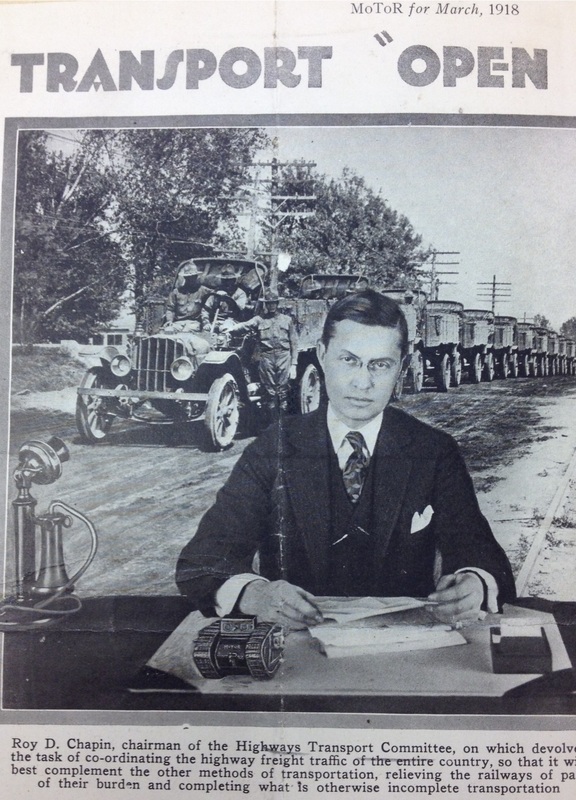

By the spring of 1917, the dire situation along the Western Front made Britain increasingly dependent on American finance, foodstuffs, and war material. The United States’ unique position as a neutral country allowed it to profit greatly from supplying the Allies, despite the disruption that was caused by German U-boats in the Atlantic. However, when the United States entered the war in April, it shouldered the responsibility of supplying not only the French and British forces along the Western Front, but also its own expedition force. This put strenuous demands on the American economy. America’s intensive wartime mobilization can be understood as a response to these demands, but merits study for other reasons as well. While the war forced both government and business to integrate their operations on a massive and nation-wide scale, the prevailing influence of local economic actors marked the history of American mobilization [1]. Michigan alumni like Howard E. Coffin and Roy D. Chapin from Hudson Motors became prominent national figures inside the Council for National Defense, an advisory board that was established to organize national industry during mobilization. Louis C. Walker, another Michigan alumnus and a banker from Muskegon, worked tirelessly to help secure and finance Liberty Loans. The federal government’s dependence on private enterprise during the First World War provided an opportunity for these local actors to make their mark on the wider war effort. It also spurred a wave of integration between the government and private enterprise that brought a host of other complications along with it.

Southeast Michigan’s auto industry quickly became one of Wilson’s closest industrial allies during the war. Besides the strange exception of Henry Ford, the auto industry was almost entirely in favor of war with Germany. Henry B. Joy, the president of Packard Motors, became an advocate for interstate transport through his Lincoln Highway Association and argued successfully for its usefulness in allocating war materiel. Joy was also instrumental in designing and producing the Liberty Engine, a powerful aircraft motor developed to government specifications. Roy D. Chapin of Hudson Motors, while also an advocate for domestic highways, found success in producing trucks and ambulances for the military. Cadillac Motors also benefited from the production of wartime trucks and aircraft engines. Auto industrialists would also use the war and the motif of civilian self-sacrifice to attack organized labor. Patriotic workers were encouraged not to strike or give up on their jobs [2]. The auto industry’s ability to capitalize on the war thus included attacks on labor, the production of war materiels, and the establishment of a powerful relationship between the government and auto industry executives.

The war effort was also supported by various educational institutions across the United States, through both recruitment programs and military research. Campus organizations like the SATC brought a sense of mobilization to students and faculty. In many cases, it wasn’t always students who were pulled into the war effort--faculty members helped as well. Moses Gomberg’s research on the development of mustard gas at the University of Michigan brought him into close correspondence with the War Department’s Chemical Warfare Service [3]. Alumni, however, would have the greatest influence on university affairs. Pro-war alumni at Michigan would spearhead the purge of the German department as well as offer up large grants and fellowships that would bring research closer to local industry. Chapin, for example, once a student at Michigan, established a fellowship in highway engineering. This relationship between businessmen and alumni would continue to grow throughout the war.

Businessmen quickly found that opportunity was no enemy of patriotism, and despite the outcry of progressives and public officials,[4] business interests seemed to take precedence over government interests in the ongoing integration process [5]. Profiteering was an ongoing problem throughout American mobilization, and it garnered an unbridled level of dissatisfaction inside Washington. One journalist derided profiteering during wartime as “a sin against country and humanity”[6]. Despite this condemnation from the public, aggressive opportunism continued. Even the War Industries Board, which sought to provide regulation to the allocation of war resources and materiel, was given such limited authority over such a small span of time in the mobilization effort that its overall effect was quite small [7]. The Wilson administration’s fear of exercising any coercive power over the nation’s economic sector only entrenched the collusion between private enterprise and the government, planting the seeds for the laissez-faire principles and steady militarization that marked the following decade. Therefore, the initial seeds of the modern military-industrial complex can be seen as having been planted during the Great War.

Notes

Please click images for full descriptions and citations

[1] David Kennedy, Over Here: The First World War and American Society, (New York: Oxford University Press, 1980), 94.

[2] Stick to the Job You’ve Got, Edgar A. Guest Papers, Box 5, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

[3] Correspondence, Moses Gomberg Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

[4] William Cameron, Washington in War Times: A Series of Articles Published in The Detroit News, July 29--August 22, 1918 (Detroit, Michigan: Detroit News, 1918), 31.

[5] Kennedy, Over Here, 127.

[6] Cameron, Washington in War Times, 32.

[7] Hugh Rockoff, "Until It's Over, over There: The US Economy in World War I," in The Economics of World War I, edited by Stephen Broadberry and Mark Harrison (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), 328.