International Humanitarian Aid

The Michigan community swiftly responded to the humanitarian crisis in Europe and beyond. On October 15, 1914, members of the American Red Cross, the Daughters of the American Revolution, and the Cosmopolitan Club organized a spontaneous mass meeting on campus in Hill Auditorium. The idea was to “stimulate interest in the international work of the American Red Cross” and raise funds to support its humanitarian work in Europe. In the course of that one meeting, the town raised $503.60 - roughly $8,700 in modern currency- to be equally distributed among all warring nations, unless the donor had a request for a particular destination [1]. Though this attitude of universal distribution would fade as the United States officially entered the war, it is important to realize the initial outpouring of fundraising was for humanitarian aid for all nations affected by the war, regardless of the side they fought for.

In time, however, civilian anguish in Belgium, Poland, and the Ottoman Empire took precedence in the minds of University students, giving rise to a local volunteer movement. Though some were reluctant to divert attention from their research, studies, and campus revelry, a significant number of University students and faculty volunteered their time and energy to gather aid money to help strangers in foreign countries. What is notable is that international humanitarian relief brought together the University and Ann Arbor communities in a collaborative effort. The relations between the student body and Ann Arbor townsfolk had been tense from the time the University had been established in 1817 [2]. These divisions, it seems, were softened during the war, as female, as well as male students, began working with Ann Arbor community members toward the common goal of aiding those in need.

The Belgian Dilemma

The first international cause taken up systematically on campus was that of Belgian civilians. On August 3, 1914, Germany amassed its troops along the borders of Belgium in preparation for a move onto France. The following day, Germany invaded the country despite international warnings, breaking international law by violating Belgian neutrality mandated in 1839. The invading German forces faced unexpected resistance from the Belgian army. Consequently, the German command ordered a quick and forceful move into the country. Within a few days of the invasion, rumors spread of German ‘atrocities’ against civilians. Many fled the war zone, contributing to what scholars have called the first refugee crisis of the twentieth century. Others remained in the occupied zones and were exposed to violent retributions from paranoid German troops. The Allied press quickly took up these stories and the suffering of Belgian civilians remained a daily news item until at least October [3].

The situation grew worse when Belgium began to experience extreme food shortages by virtue of being a country, in a war-damaged international market, that mostly relied on food imports to feed its population. Indeed, it only produced enough food to feed about 20-25 percent of its people. Additional pressures from German requisition of existing Belgian food supplies and an Allied economic blockade targeted at the occupying Germans only served to aggravate the shortages. When famine threatened, the international community rallied to provide aid to those starving in Belgium. At the forefront of this relief effort were organizations such as the Commission for Relief in Belgium (CRB), headed by Herbert Hoover [4]. Through the CRB, Hoover coordinated imports of food and other supplies to Belgium to prevent an impending famine. Hoover continued to work with the CRB until the United States joined the war in 1917, at which time he returned to the United States to head the United States Food Administration.

"Save the Starving Children"

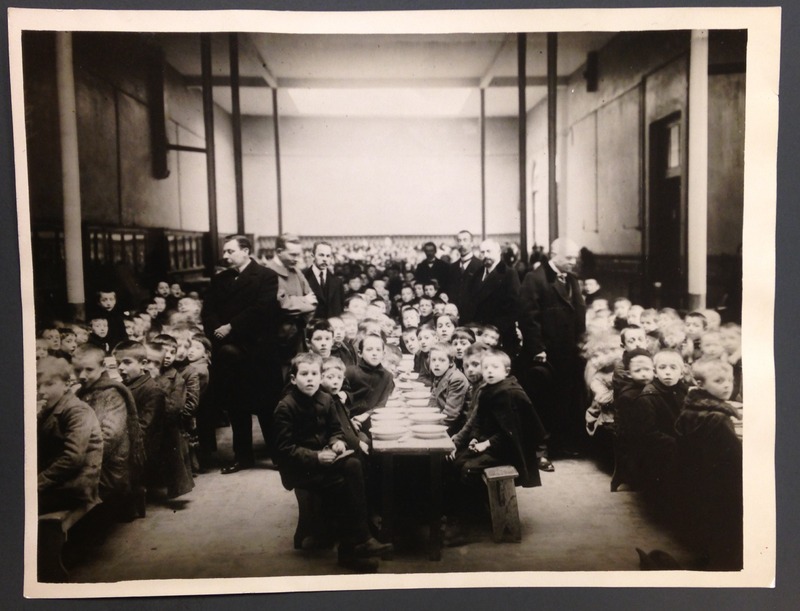

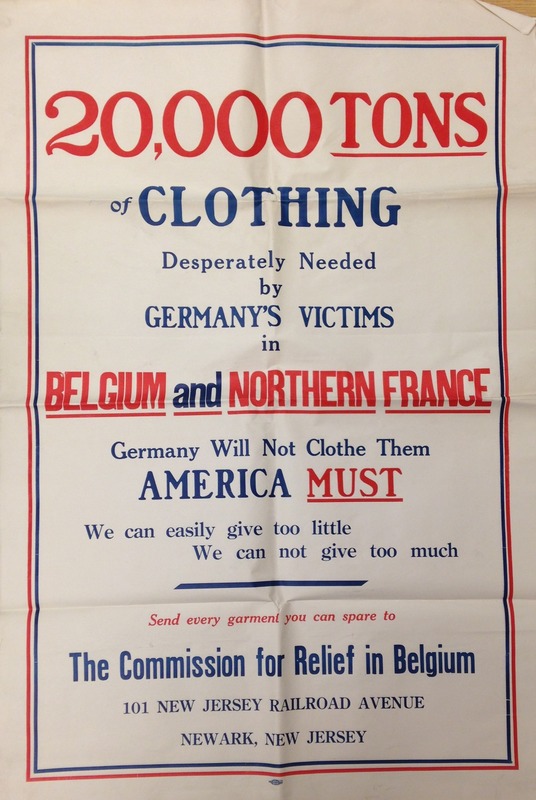

Organized efforts to collect money, food, and clothing for Belgian civilians and orphaned children began when American Red Cross workers visited Ann Arbor schools in the fall of 1914. The historian John Pedley points out that it was difficult for Ann Arbor children to make sense of the problem: “they had no idea where Belgium was, but they had classmates of German extraction, or blood, in their everyday lives”[5]. While perhaps challenging to grasp for children, the adults of the community and female students from the University no doubt read the international news and kept informed about the situation. Many even made efforts to hear a group of Ann Arbor women speak about their experiences with the miseries abroad. Inspired to help those in need, female students joined local Ann Arbor women to sew garments in the halls of the Church of Christ building on South University. The work began in November of 1914, and in time, the Church of Christ turned into a “Clothing Factory for European Sufferers,” under the direction of its Reverent. About fifty people gathered here daily and produced roughly 800 garments every week [6]. Also, clothing drives amassed large quantities of donations. An article in The Michigan Daily quoted a single drive in 1918 that received over two tons of clothing [7]. By March 1918, the youth of Ann Arbor had gained a better understanding of a world at war and enthusiastically volunteered to collect suits, shirts, jackets, for Belgian Relief [8]. Ann Arbor residents continued to organize clothing drives for the entirety of the war.

Fundraising

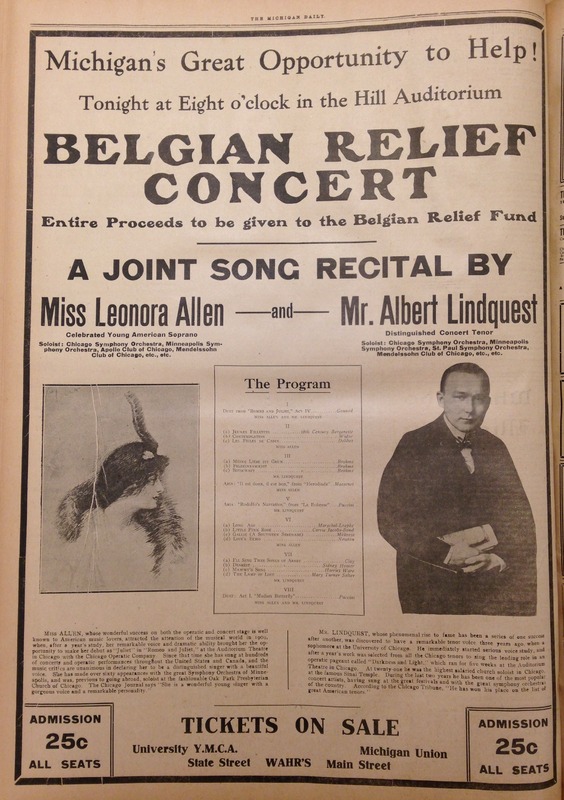

Significant funds were necessary for the success of this effort. While initially most of the donated money came from Ann Arbor residents, students were another lucrative source of funds, work, and materials. Many female students raised money planning events. Some hosted “card party” social activities, while others convinced one of the many theater owners to donate a portion of ticket sales for one of the performances to the Belgian Relief effort. Although female students readily gave their time and effort to the cause, male students were less invested in contributing. To encourage male participation, Ann Arbor women and female students organized a committee to canvass fraternities, house clubs and rooming houses for clothing and money. Upon request from the committee, The Michigan Daily published calls to action asking students, for example, to donate 25 cents so that “sufficient clothing may be provided to keep one child warm the entire winter”[9]. At times, the editors chastised male students’ ambivalence to the suffering abroad. The combination of appeals and public embarrassments proved to be effective. Men soon began sending out circular letters to class presidents and heads of fraternities and house clubs, asking for their cooperation in raising contributions [10]. On December 2 1914, students and townsfolk came together to secure one thousand suits to send to Belgium. The next event was a concert to “Aid Starved Belgians” on January 14th, 1915, that was attended by 1500 people [11].

The efforts slowed in 1916 following this initial outpouring of communal sympathy for strangers abroad, even when the news of the horrific situation in Belgium continued to arrive in Ann Arbor. Paul van den Ven, a Belgian professor of Philology, came to Ann Arbor to lecture about his research. During the reception held in his honor, the visitor spoke of the situation in his country to attendees. Van den Ven's and other first-hand accounts moved Latin Professor Francis W. Kelsey, who eventually would revive the Belgian Relief efforts in the spring of 1917. It was in that year that Kelsey recruited some of his colleagues and Ann Arbor townspeople to set up a Committee for the Relief of Belgian children. Among them was Charles A. Sink, who would receive a gold medal from the Belgian government “in recognition of his services for the relief of Belgium during the war” [12]. It was during a meeting with the University President Hutchins on February 2, 1917, that Kelsey, three of other faculty, and a number of Ann Arbor women, established the “Dollar-a-Month Club” to aid Belgian children.

The Dollar-a-Month Club quickly became one of the best organized and far-reaching efforts in Michigan in terms of international humanitarian aid. The Dollar-A-Month Club’s committee drafted a circular and distributed it beyond Ann Arbor city limits. The circular urged the community to pledge one dollar per month to provide “one square meal a day” to starving children for as long as the need existed [13]. By February 28, 1917, the committee had sent out approximately 20,000 promotional pamphlets by mail to cities like Manchester and Detroit. Another 6,000 were on hand to be were used in a house-to-house canvass in Ann Arbor [14]. The committee not only canvassed Ann Arbor homes but also solicited funds from fraternities, sororities and residence houses.

The Belgian Relief efforts apparently brought together the student body and the Ann Arbor community. For example, students donated their caps, which would usually be thrown into the bonfire on Cap Night, to the Belgian Relief. A local company, the Ann Arbor Steam Dye Works, often volunteered to steam clean clothing collected from students before they were sent abroad [15]. Additionally, five campus committees were formed to increase membership in the Dollar-a-Month Club and to solicit donations from various campus organizations, local clubs, residential homes, local businesspeople and the press. To expand the reach of the committee, Kelsey sent a telegram to the governor of the state Albert E. Sleeper, asking for a meeting. The committee presented its work to the governor, who not only agreed to become the chairperson of a statewide committee, but also introduced the idea in Washington. In time, Dollar-a-Month Club raised significant funds and resources statewide and sent the money collected by Hoover’s Commission for Relief in Belgium to Europe.

The Commission for Relief in Belgium worked to inform the American public. Public lectures about the Belgian horrors and information materials such as the Memoranda of Facts were distributed en masse, including postcards that depicted "debilitated children" abroad. The CRB appealed to a sense of empathy by providing detailed factual information and assuring donors that their money had a direct effect abroad. Assigning communities in Michigan to particular groups of needy Belgian children was one way of doing so.

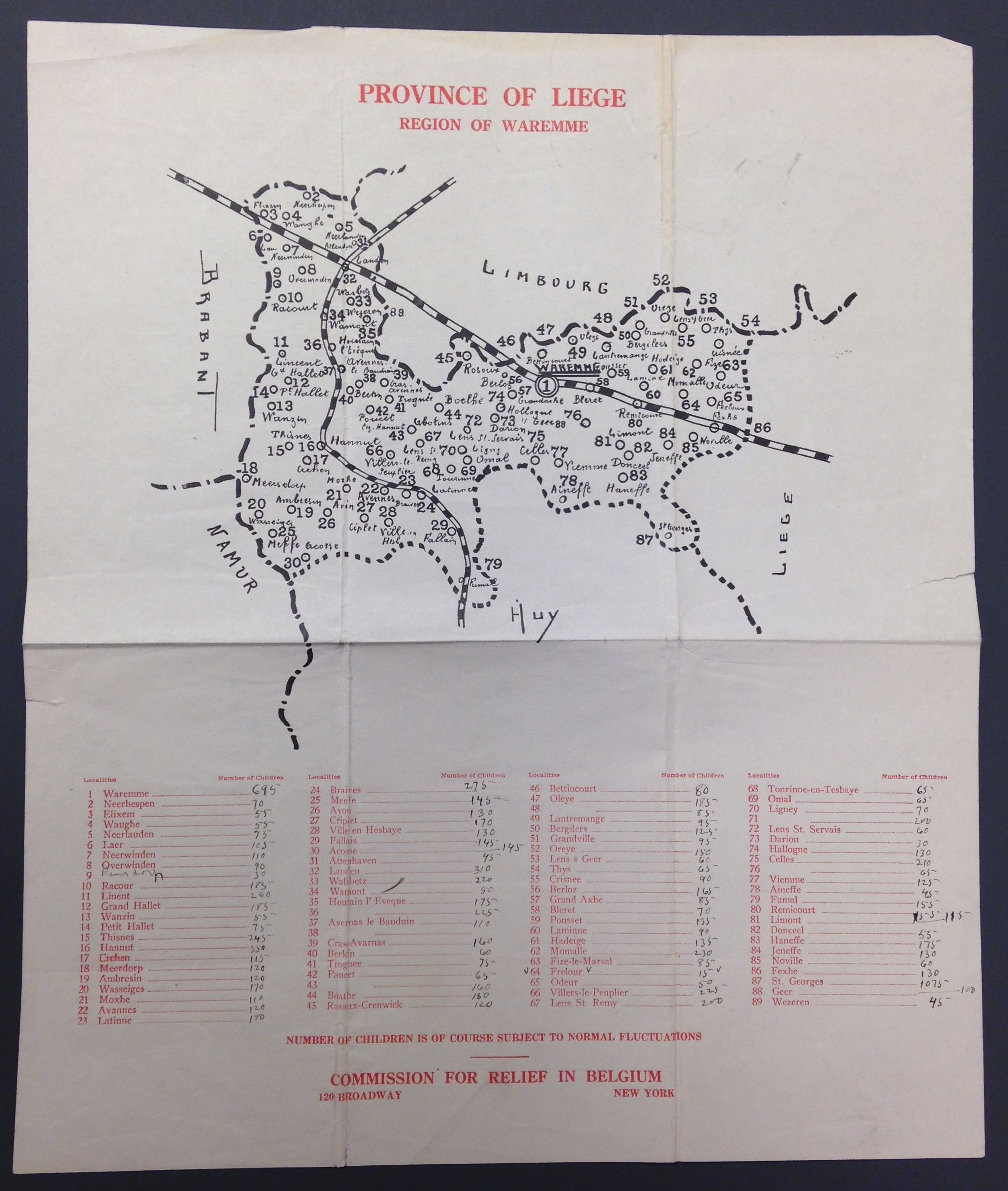

For example, whereas the statewide committee had pledged to support the children of the province of Liege, home to approximately 12,000 children in need, the American Red Cross chapter of Grosse Ile, MI. provided "supplementary meals" for the children of the town of Frelour in the Region of Waremme within the province of Liege.

This was a strategic promotional tool, as Frelour became a place members of the chapter could locate on the maps provided by the CRB (like the one displayed here) and imagine the direct impact their $15 a month made for the 15 children living in the town [16]. Moreover, aid recipients were encouraged to express their gratitude to their American benefactors, which became yet another way of assuring donors at home that their actions had immediate effects on the ground abroad.

This was a strategic promotional tool, as Frelour became a place members of the chapter could locate on the maps provided by the CRB (like the one displayed here) and imagine the direct impact their $15 a month made for the 15 children living in the town [16]. Moreover, aid recipients were encouraged to express their gratitude to their American benefactors, which became yet another way of assuring donors at home that their actions had immediate effects on the ground abroad.

It may be said that the work of the Dollar-A-Month Club committee paid off quickly, as donation envelopes filled with small dollar amounts came streaming into the committee’s office. An article in the Detroit Free Press from February 20 announced that the Dollar-A-Month Club was growing rapidly, even before the State Committee finished organizing. The Ann Arbor News from May 1, 1917, reported that two hundred Detroit citizens had donated 120,000 dollars to the Belgian Relief Fund [17]. Eventually this Ann Arbor idea, in collaboration with the state committee, was to provide $150,000 per month to the CRB. The club was disbanded when the American government began providing loans to Belgium at a national level and made local philanthropy redundant [18]. The actual amount raised by the Dollar-A-Month club before its end in the fall of 1917 was $25,000 [19].

Kelsey’s efforts attracted the attention of Herbert Hoover himself, who wrote to congratulate him on his efforts. Hoover was impressed with the success of the idea, and ended his letter hoping that his “Dollar-a-Month Club may spread its influence throughout Michigan and put the state in the front rank of patriotic and humanitarian giving” [20]. After the war had ended, Kelsey received an invitation to join a dinner held in honor of Herbert Hoover, who was returning from Europe. The dinner was arranged by American Relief Administration European Children's Fund, which was eager to invite individuals like Kelsey, who had worked tirelessly during the war. Overall, humanitarian activism on behalf of Belgians came to be an important part of the Michigan home front culture during World War I.

Polish Relief

In addition to their Belgian Relief contributions, University of Michigan students of various ethnic and national backgrounds organized to provide aid to their ancestral communities abroad. For example, Polish students of the university organized to provide humanitarian assistance for Poland in February of 1915. The students described the situation in terms of the Belgian Relief movement, declaring “Poland in the East, like Belgium in the west, is the battleground of present terrible conflict in Europe,” and “the official Rockefeller commission reported that the situation in Poland was worse than in Belgium” [21]. Students also organized similar events to those used in Belgian Relief as they worked to raise funds to contribute aid. The Polish sympathizers collaborated with the proprietor of the Arcadia movie theater in Ann Arbor to secure one thousand tickets whose proceeds would benefit relief efforts in Poland [22].

The students also organized a lecture in Hill Auditorium. The speaker, James Archiboldt, worked as a war correspondent and showed a film of the European front lines. Again, the revenues from ticket sales financed aid abroad. W.H. Hobbs, professor at the University and National Security League advocate, criticized this lecture for its neutral portrayal of German soldiers. Though the Polish Relief on campus never garnered the same level of statewide support as the Belgian Relief efforts, the money gathered represented the willingness of the American people to provide humanitarian support for individuals they had never and likely would never meet.

Armenian Relief

Another community deeply affected by the war were Christian Armenians in the Ottoman Empire [23]. On receiving reports about massacres and genocide perpetrated by the Young Turk regime against Armenian civilians, the University’s Armenian Student Association (ASA) organized a statewide campaign in October of 1915. The Association requested that ”every member would aid in doing all possible to raise funds for the benefit of the needy in the fatherland” [24]. The ASA staged a concert was organized in Hill Auditorium to raise money. Hill Auditorium would, for the first time, feature professional Armenian singers and musicians. The money collected both at the Ann Arbor concert and at a similar concert in Detroit was sent to the Armenian National Church to be used at its discretion.

By 1916, eyewitness accounts published in The Michigan Daily declared that the situation in the Ottoman Empire had grown worse than in Belgium. For example, on January 8, 1916, the paper published an essay from Aredis Koumjian, ‘16. Aredis had received a letter from his cousin who had escaped the massacres and ended up in the Caucasus in Southern Russia with 200,00 other refugees.

I was teaching in Malashgert, near Van, when the governmental orders reached us to start off for nobody knew where. The governor of Van had already treacherously killed a number of leading Armenian citizens. The remaining leaders of the people held council and resolved not to surrender to the government and with the gruesome fate of the other cities that had obeyed orders before their eyes, the youth of the city took up arms, followed by the older men, and by some women [25].

Another article published on March 3, 1916, reported that Professor Nahigian, an old Michigan alum, had been killed alongside three other professors during the massacres in Harpoot. The same article also noted that 1 million Armenians had been killed [26]. Here as in other relief efforts students collaborated with the larger Ann Arbor community and organized charity events for the “unfortunate Armenians” [27].

Moreover, the campus community contributed to greater national efforts organized by the American Red Cross and the American Committee for Armenian and Syrian Relief (ACASR). For example, the ASA with other student groups designated October 28, 1916, to be a “tag day” at the Michigan Union. The goal was to contribute to the five million dollar goal set by national relief organizations. When President Wilson proclaimed a national relief day “for the stricken Christians of Turkey” in October of 1916, the ASA made sure it was observed on campus [28]. Though the efforts to provide aid likely continued after 1916, the mentions of Armenian Relief in The Michigan Daily petered out between 1917 and 1918. The local focus turned to American troops and interests in the war as well as the more prominent local relief efforts.

Though the destination of donated aid varied based on personal investment, Washtenaw County contributed significant amounts of money, clothing, and supplies to international humanitarian causes. The campus and the Ann Arbor communities collaborated, and some of their efforts gained state and nationwide attention. Once the United States entered the war, the mobilization on home front added war relief to American soldiers to its efforts.

Notes

Please click images for full descriptions and citations

[1] The Michigan Daily, October 15, 1915.

[2] Fred B. Wahr, “The Students and the Town,” in Walter A. Donnelly, Wilfred B. Shaw, and Ruth Gjelsness, eds. The University of Michigan: An Encyclopedic Survey Vol. 4. ( Ann Arbor: University of Michigan, 1958), 1777.

[3] John Horne,and Alan Kramer, German Atrocities, 1914: a History of Denial (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2001), 1.

[4]"Michigan Help for Belgian Children," Michigan Alumnus, 23 (1917), 371.

[5] John Griffiths Pedley, The Life And Work of Francis Willey Kelsey: Archaeology, Antiquity, And the Arts ( Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2012), 251.

[6] The Michigan Daily, November 29, 1914.

[7] The Michigan Daily, April 2, 1918.

[8] The Michigan Daily, March 22, 1918.

[9] The Michigan Daily, November 11, 1914.

[10] The Michigan Daily, November 28, 1914.

[11] The Michigan Daily, January 16, 1915.

[12] The Michigan Alumnus, 27 (1921), 608.

[13] "Michigan Help for Belgian Children," The Michigan Alumnus, 23 (1917), 317-319.

[14] Letter from Francis W. Kelsey to George Baker, February 28, 1917, Box 86, File 3, Kelsey Museum of Archaeology Papers (1890-1979), Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

[15] Letter from Francis W. Kelsey to The Ann Arbor Steam Dye Works, August 21, 1917, Box 86, File 1, Kelsey Museum of Archaeology Papers (1890-1979), Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

[16] Letter from George Baker to Francis W. Kelsey, March 5, 1917, Box 86, File 3, Kelsey Museum of Archaeology Papers (1890-1979), Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

[17] Ann Arbor News, May 1, 1917, Box 87, File 21, Kelsey Museum of Archaeology Papers (1890-1979), Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

[18] "Michigan Help for Belgian Children," The Michigan Alumnus, 23 (1917), 317-319.

[19] Michigan Alumnus, 27 (1921), 608.

[20] as quoted in Pedley, The Life And Work of Francis Willey Kelsey, 252.

[21] "Michigan Help for Belgian Children," Michigan Alumnus, 23 (1917), :317-319

[22] The Michigan Daily, February 14, 1915.

[23] For a detail account on the events in the Ottoman Empire see Ronald Grigor Suny, "They Can Live In the Desert but Nowhere Else": a History of the Armenian Genocide (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2015); Raymond H. Kévorkian, The Armenian Genocide: a Complete History (London: I. B. Tauris, 2011).

[24] The Michigan Daily, October 15, 1915.

[25] The Michigan Daily, January 8, 1916.

[26] The Michigan Daily, March 4, 1916.

[27] The Michigan Daily , October 25, 1916.

[28] The Michigan Daily, October 25, 1916.