A Selection of Organizations for War Relief in Ann Arbor

The Y.M.C.A and the Y.W.C.A.

Many relief organizations active during before the Great War, such as the Young Men's Christian Association (YMCA) and the Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA), had been established prior to it. The YMCA began relief work and its building in Ann Arbor became the initial meeting ground for those interested in helping. [1]. After the establishment of a chapter of the Red Cross in 1917, the YMCA, and the YWCA shifted to support the Red Cross and the Women’s Committee of National Defense. The YMCA raised funds through their War Work Fund. Their motto was “Give Until it Hurts,” and reports of its fundraising filled the pages of The Michigan Daily throughout the 1917-18 school year [2]. Though the YMCA “War Chest” was eclipsed by fundraising through the Red Cross and Liberty Loan drives, the organization funded its own overseas war relief efforts [3]. Internationally, the YMCA provided entertainment for soldiers, as well as coordinating cheap lodging and entertainment for Americans during wartime. Lewis H. Fead, a hospital representative with the Red Cross, traveled along the war front after the end of the war by making use of the YMCA institutions available for other Americans performing the same trip [4]. Both the YMCA and the YWCA maintained their multi-faceted relief effort until the end of the war in 1918.

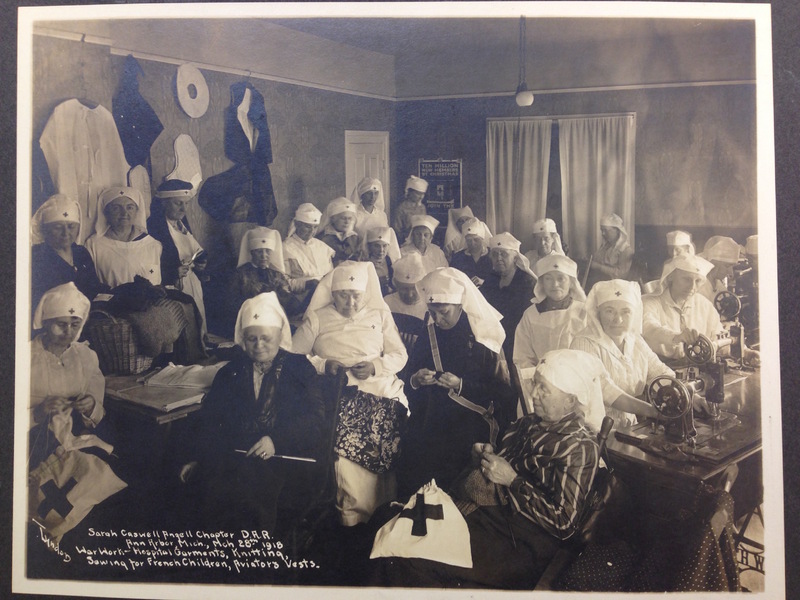

The Daughters of the American Revolution

The Michigan women founded their branch of the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) in 1896. Headed by Mrs. James Burill Angell, they women helped to knit, provided for French orphans, and purchased thrift stamps and Liberty Bonds[5]. The women sold yards of lace made by French women. One of the most active women in this effort, Mrs. William H. Wait, received a medal for distinguished service by the French government [6]. The DAR 's work at times was quite particular. For example, the Ann Arbor women knitted garments for 32 sailors of the torpedo ship “Captain Tingey.” The report of the Chapter Historian mentions the personal attachment forged toward this group of men by virtue of knowing exactly where their donations were going [7]. The DAR promoted patriotism among Ann Arborites. Antiwar voices were unacceptable, and when Emma Goldman wanted to speak on campus in 1918, the DAR petitioned the mayor to prevent her two talks [8].

Ann Arbor Civic Association

The Ann Arbor Civic Association also threw their efforts behind sewing garments and the production of surgical dressings. The Association reported nearly 3,000 surgical dressings and a vast amount of clothing gathered and sent to Paris by 1916, before the Red Cross had even been established in Ann Arbor [9]. They were also instrumental in establishing an official American Red Cross chapter in Ann Arbor, a process that stretched from the beginning of the war in Europe in 1914 to its establishment in 1917 [10]. The Ann Arbor Association was a city organization though they appealed to college students to contribute to their fundraising. Donation boxes were placed by the organization in University buildings, though they were largely unable to encourage students to contribute to their organization over others, even when the students were given the option to choose where the money should go. Though the total amount of money raised from University students was only $30, this was enough money to fund ten high grade children’s coats, 72 muslin slighs, and 1,200 gauze dressings” [11].

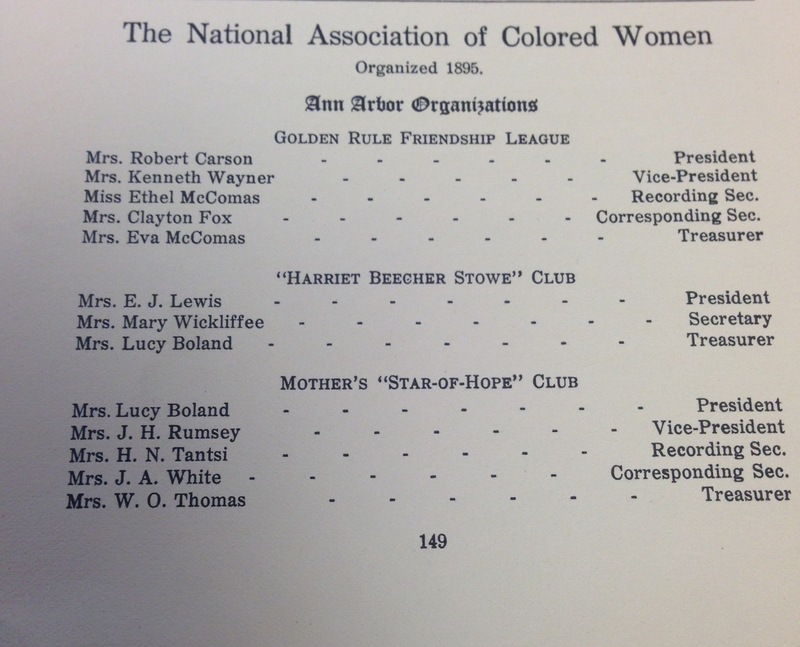

The Golden Rule Friendship League, the “Harriet Beecher Stowe” Club, and the Mother’s “Star-of-Hope” Club

Though there was no mention of their work outside of the Ann Arbor Negro Yearbook, there were also three women’s committees as a part of the National Association of Colored Women active in Ann Arbor. The Golden Rule Friendship League, the “Harriet Beecher Stowe” club, and the Mother’s “Star-of-Hope” Club would have been just as affected by the home front’s patriotic fervor, though no record of their work was found in the Bentley Historical Library by the Michigan in the World Project [12]. Despite being published in Ann Arbor, the Yearbook largely focuses on the work done in Detroit by the National Negro Urban League. The National Negro Urban League focused its efforts on assisting black immigrants from the south settle into the urban center of Detroit by securing lodging, locating vacant jobs, and providing social services as large numbers of black Americans moved northward across the country during the war period [13].

Notes

Please click images for full descriptions and citations

[1] Feb. 7th, 1917, Red Cross Chapter Minutes, American National Red Cross, Washtenaw County, BHL

[2] The Michigan Daily, 1917-1918, BHL

[3] The Michigan Daily, 1917-1918, BHL

[4] Mementos, Box 6, Lewis H. Fead Collection, BHL

[5] Mrs. Arthur Smith, “The 30th Anniversary of the Sarah Caswell Angell Chapter, DAR, (1926).” Folder 14, Box 27, Daughters of the American Revolution Collection, BHL

[6] Mrs. C.H. Millen “Report of the Chapter Historian (1916-1917)” Folder 14, Box 27, Daughters of the American Revolution, BHL

[7] Lavinia Gould MacBride, “Report of the Chapter Historian (1917)” Folder 14, Box 27, Daughters of the American Revolution, BHL

[8] Detroit Free Press, January 19, 1918, Clipping, History of the Radical Movement in Ann Arbor, 1918, Labadie Collection

[9] The Michigan Daily ,January 3, 1916

[10] “The Chapter Role” Folder: History, New Version, Box 1 American National Red Cross, Washtenaw County Chapter, BHL

[11] The Michigan Daily, March 22, 1916

[12] The Ann Arbor Negro Year Book,149, BHL

[13] The Ann Arbor Negro Year Book,151, BHL