Censorship

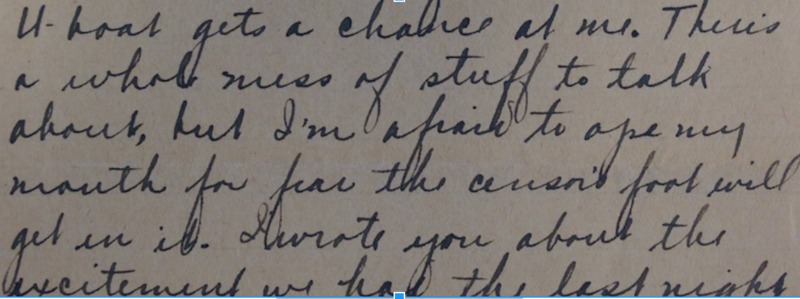

“There is a whole mess of stuff to talk about, but I’m afraid to ope my mouth for fear the censor’s foot will get in it.” -- Kenneth A. Easlick.

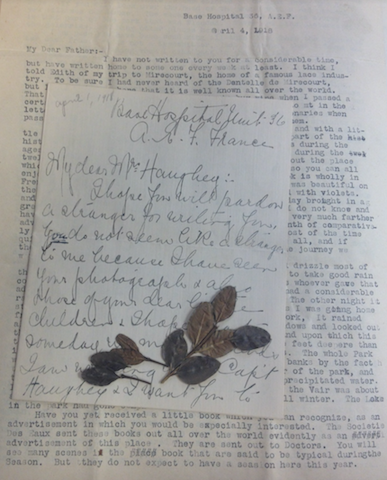

During World War I, letters, diaries, memoirs, songs, and poetry comprised the main forms of reflection upon the war, with letters and diaries taking the forefront. Many of these documents have been preserved and are available for perusal today. Often addressed to family, friends, and sometimes a student’s professor, these letters discussed daily activities, sights of France, requests for chocolate, cigars, or clothes, and many reassurances to loved ones. The letters, however, provide little information as to the location of the troops and plans for or predictions about the war.

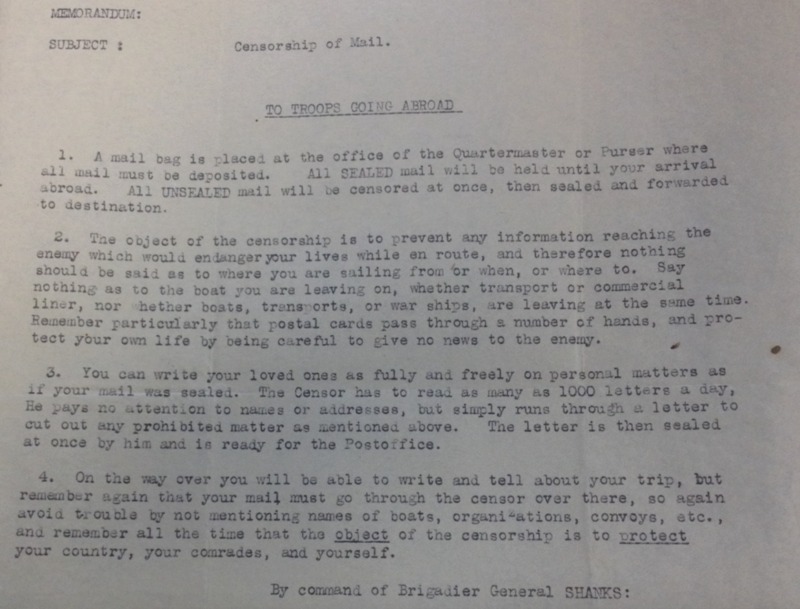

In a moment where bombs, battles, and borders were at the forefront of civilians’ minds, it is curious that the bulk of discussion in soldier’s letters did not focus on such topics – despite appeals for such information. The answer to the lack of detail on the more miserable and violent aspects to the war appears to be twofold. At one level, soldiers were instructed not to include information about their company’s location; for fear that the enemy would intercept the letter and gain valuable tactical information. On November 17, 1917, the general orders for censorship of mail from soldiers were issued. (Below is an image of this order.) The purpose of the order was clear:

“The sole object of field censorship and all other steps taken to prevent the leakage of military information is to secure success of our own and allied operations with the least possible loss [1].”

Soldiers appeared hesitant to relay any information that may cause distress to their loved ones, instead choosing to discuss lighter topics and comment on the comforts with which they were provided. For example, Kenneth A. Easlick, of Ridgeway, Michigan, graduated from University of Michigan in 1917, after which he joined the U.S. Army Ambulance Service. Following the war, he returned to the University of Michigan to get a degree in dentistry. In the course of the war, he wrote letters home to his family. In one letter Easlick directly mentions his intention not to discuss the nastier aspects of the war. “There is a whole mess of stuff to talk about, but I’m afraid to ope my mouth for fear the censor’s foot will get in it [2].”

On another level, soldiers apparently made an effort to discuss the pleasant aspects of their time in the war, which included traveling to villages across France, the food, accommodations, and people whom they met. Perhaps as much can be understood about the soldier experience from what is not written as from what is written.

Overall, diaries and letters of soldiers show us that on one level government imposed restrictions on letter writing was one reason the men often excluded gory details or more particular aspects of the military’s activities. Another, perhaps stronger, motivation for soldiers to relay the most positive aspects of their experience was to reassure their families of their safety, happiness, and likelihood of victory in the war. In a sense, they were telling one side of a two-sided experience in the war. The boredom and monotony of training camps, the new sense of union and camaraderie as well as tests of physical and mental capacity, related in letters to their families were not competing experiences of soldiers’ life. Instead, these were all aspects of the soldiers’ training camp experience. Soldiers appreciated their opportunities to travel France, seeing all the beautiful landscapes, making friends with soldiers from England and France, as well as seeing shows, eating new foods, and forming everlasting friendships within their own company. These were perhaps the most pleasant aspects of their wartime experience and thus the aptest ones to write about to their families. These accounts to no doubt reassured their loved ones of their safety and likelihood of surviving the war. Thus, through censorship -- both government and self-imposed, letters display one side of the soldier experience and diaries another.

Notes

Please click images for full descriptions and citations

[1] Harry Crawford, World War 1, United States Army in the World War. General Orders 146. Box 1, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

[2]Kenneth A. Easlick Papers 1924-1979, Box 1, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.