Life on the Front: Aiding the Wounded

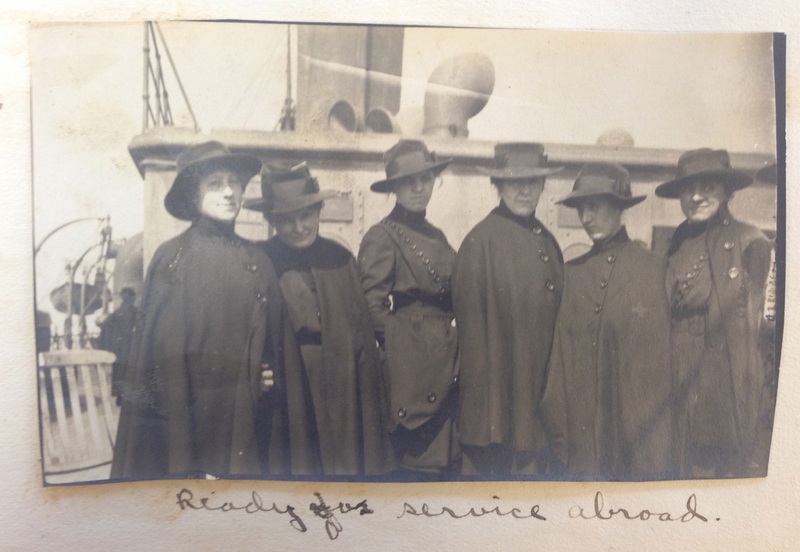

For soldiers who were wounded in the first few weeks of World War I, the first responders were often the ambulance units. Ambulance drivers drove their wagons and carriages up to the front lines to transport the wounded back to the safety of the nurses and doctors in the triages. But with artillery continually improving in range and accuracy, battlefield triages, and hospitals were moved further back behind the front than they had been in previous wars, exacerbating the load faced by already strained horse-carriage ambulances [1]. In response, ambulance services enlisted the help of automobiles. The first use of motorized ambulances in World War I can be traced to Richard Norton, who organized the first modern ambulance corps in October 1914, just months after the outbreak of war. With its continual use of the motorized ambulance, Norton’s American Volunteer Motor Ambulance Corps revolutionized ambulance duties on the front. It became the United States’ first ambulance volunteer unit to serve with the French and the British. Norton became so dependent upon his automobiles that he was often found writing letters to American industrialists in Detroit, pleading for donations of new vehicles [2]. By 1917, Norton’s fleet of American automobiles and drivers became recognized for their humanitarian aid. France awarded Richard Norton the Grand Cross of the Legion of Honor, France’s highest decoration for which a foreigner is eligible [3].

While Norton’s American Ambulance Corps was directly affiliated with the American Red Cross, the American Ambulance Field Service, another volunteer ambulance division, chose to be integrated directly within the French Army. Both the American Ambulance Corps and the Field Service chiefly employed college students, graduates, and university faculty in their ambulance divisions, fostering a sense of prestige and genteel tradition around ambulance divisions [4]. Although the vast majority of ambulance drivers came from the nation’s most renowned schools, specifically Harvard and Yale, institutions around the country committed student after student to ambulance duties. The University of Michigan was no exception, with over 30 students in the Field Service by the end of 1916 [5]. By June of 1917, the expansion of the Field Service and the United States’ entry into the war prompted the Army to federalize the Field Service, forming it into the United States Army Ambulance Corps, and recruitment spiked once again on campuses across the country.

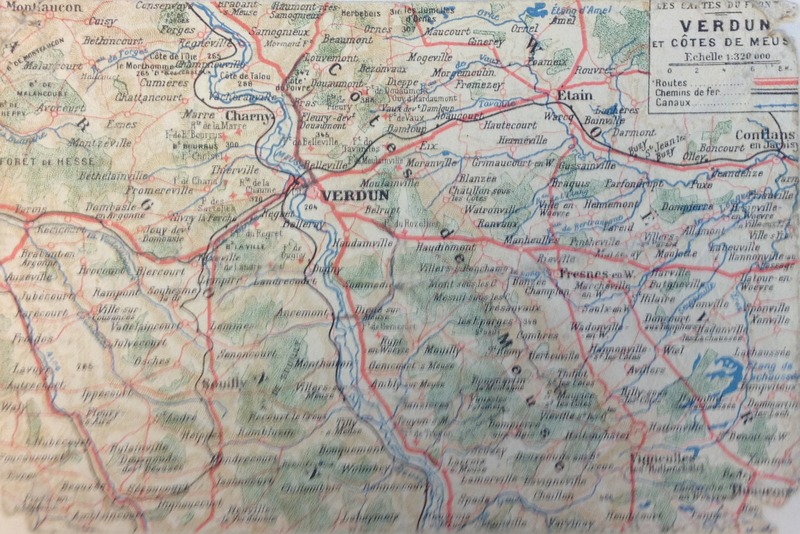

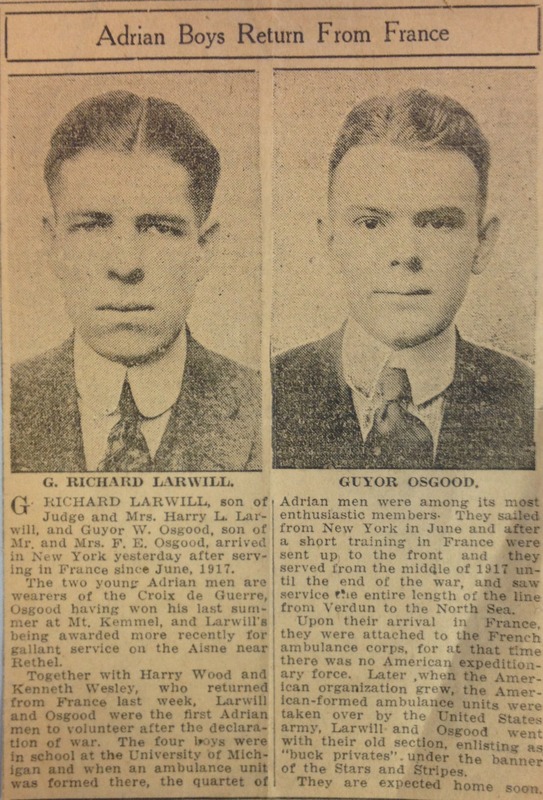

At the University of Michigan, enough students, alumni, and faculty enlisted into the Army Ambulance Corps to form three separate divisions: the 589th, the 590th, and the 591st [6]. Each division trained in Allentown, Pennsylvania before heading off to France, where they were attached to the French Army since the American Expeditionary Force had yet to open up its front. For William Edward Votruba, an undergraduate student at Michigan, joining the ambulance corps was an opportunity to enlist and help the war effort while refraining from firing a gun [7]. Despite their removed position on the battlefield, Michigan ambulance drivers often found themselves in harm’s way. Dean C. Scroggie, a medical student, was gassed twice during his time in the Army Ambulance Corps [8]. Likewise, Votruba noted that shelling from German artillery posed a constant threat for ambulance drivers, both while on the road and at triages [9]. Michigan ambulance drivers did, however, glean a view of the battlefield, and perhaps the whole of the western front, that most infantry could not possibly see. Guyor W. Osgood, a Michigan graduate from Adrian, who won the Croix de Guerre for his work, kept extensive field notes and maps of troop movements, and was privy to special intelligence bulletins [10]. Osgood’s understanding of the war differed from others because of the mobility that his ambulance afforded him; whereas most soldiers spent weeks and months in one trench, in only one part of the line, Osgood travelled up and down the front, taking photographs as he went. Photos taken by Osgood depict various parts of the line and scenes from every Allied offensive from September of 1917 until the war’s end.

Ambulance drivers tended to understand the war differently from infantry in other ways as well. It is no secret that many American ambulance drivers became famous writers, actors, and artists after the war, including E.E. Cummings, Ernest Hemingway, Malcolm Cowley, and John Dos Passos. Many ambulance drivers turned to writing memoirs and novels, and diaries of their experiences were often long, poetic, and descriptive [11]. The nature of their service, their tendency to be educated youths, and their bird’s eye view of the battlefield may have inspired artistic responses. The American Field Service no doubt enhanced this phenomenon with the establishment of the American Field Service Fellowship after the war, which sent young Americans and ambulance drivers, like Malcolm Cowley, to France to provide humanitarian aid [12]. Many ambulance drivers continued to influence the public’s understanding of the war through literary works, such as Cummings’ "The Enormous Room" and Passos’ USA: 1919, which were critical of the war’s seemingly needless bloodshed. For most ambulance drivers, the war represented not only an opportunity in their careers and a chance to help their country, but also an emotional experience that would continue to shape them for years after the war.

The American Red Cross Overseas

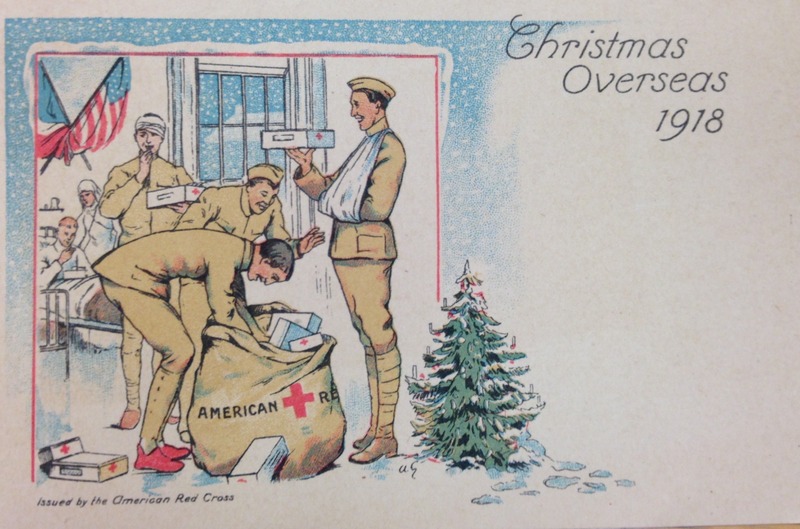

In addition to Richard Norton’s American Volunteer Motor Ambulance Corps, the American Red Cross (ARC) opened opportunities for American volunteers. The ARC's work overseas included twenty-five countries. The work began in 1914 and continued until the 1920s in [13]. Men and women from across the United States, including students and alumni of the University of Michigan, volunteered in a variety of services.

Volunteers with previous medical experience worked as doctors, nurses, or nurses aides in the military or “base” hospitals across France. L. May Helmer, an alumnus of the University of Michigan School of Nursing, volunteered in September of 1917 and was assigned to multiple base hospitals across France during her service. In her journal, she described the work of the hospital staff. Besides taking care of the wounded, nurses befriended soldiers, made chocolate fudge close to Christmas, handed out the “Christmas bags” provided by the ARC [14]. Moreover, Helmer and her colleagues rolled bandages to contribute to overall ARC supplies while stationed in Paris [15]. In general, the women were asked to keep a cheery demeanor.

But not everything was cheery of course. After all the base hospitals were close to battlefields. Bombs, wafting noxious gasses, infectious disease, were an everyday threat. The chaos and dangers meant that volunteers often were exhausted and experienced trauma akin to those of the soldiers. Still, Helmer tried to assure her sister at home that she was in no danger. Her letters were always positive, filled with hope, and positive anecdotes. Though most American nurses served in France, some worked in Poland, Serbia, Germany or Syria: anywhere the Red Cross provided aid [16].

The army and the ARC coordinated their efforts through hospital representatives. One such hospital representative was “Judge” Louis H. Fead. A graduate from the University of Michigan law school in 1900, Fead worked as a circuit judge in northern Michigan before volunteering to serve in France. He became the hospital representative for Base Hospital 34 in Nantes, France. Here the Red Cross worked to provide “everything which may be for the benefit of the patients, personnel, nurses, and officers of the institution” [17]. As hospital representative, Fead received a modest budget to “do anything I found necessary or advisable to help those attached to the hospital”[18]. He worked to install a Red Cross commissary and listened to the wishes of the injured. In a letter to his hometown newspaper, he described how “a large majority of the patients did not have even toothbrushes or handkerchiefs. I thought that an American soldier was at least entitled to clean his teeth and blow his nose like a man and the first thing I did was to buy handkerchiefs and toothbrushes and supply all the patients with them”. Fead did his best to accommodate the men's wishes. Occasionally, he got in trouble with his superiors, especially when his expenditures exceeded the budget. For example, he writes:

“One of [the nurses] told me one day that the doctors had asked for a bottle of beer for a patient and asked me what to do. We bought the beer and I understand it made a considerable fuss in Paris when my report went in. I got a searching letter of inquiry but when I replied that the doctor told me our beer had saved the life of the patient, Paris, in true Red Cross style, took its hands off and told me to buy all the beer in France if it would save an American soldier. I have not yet found that necessary” [19].

Moreover, Fead was in charge of building and maintaining a recreation hut at Base Hospital 34. The ARC recreation huts were to distract soldiers from homesickness. The huts provided soldiers a space to write letters, relax and offered entertainment put on by the Y.M.C.A. [20]. At the headquarters in Paris, many male and female ARC volunteers worked in army support branches, such as the Personnel Office, Civilian Relief, Home Communication, Graves Registration Service Photographic Section, and the Transportation Department to name just a few branches [21]. These volunteers ensured efficiency of the ARC.

While abroad, American volunteers had opportunities to explore Europe, at least as far as the war permitted. During their time off, volunteers visited local museums and historical sites. For example, Helmer describes the outings with her fellow nurses. The women explored both Paris and the surrounding countryside of the hospital, detailing museum exhibits and beautiful landscapes. For Helmer, this exploration provided an opportunity to reflect on her life as an American in Europe:

“The more I see of the Glory of France the more I wonder at our George Washington’s simple tastes. So often I compare Mt. Vernon with something I see here. How Washington who visited France in all her Glory could keep his tastes simple and in accord with a new country when he had the opportunity of being King is wonderful. I believe now that George Washington was a greater man than Abraham Lincoln, and I’m proud he was the Father of my country [22]."

When the war ended in 1918, ARC volunteers had a choice: return home or continue their service with the ARC. Many volunteers stayed in Europe to aid war refugees and help rebuild war-torn countries.In Bess Streaker’s “Twenty Years Later” collection recounts how men and women continued to volunteeretheir services in places such as Serbia, Turkey, and Poland before returning home to the United States [23]. Others, like Fead, traveled briefly before returning home. Instead of continuing his position with the Red Cross hospital, he took the opportunity to visit the front lines [24]. Still others, like L. May Helmer, returned home as soon as they were released from their wartime duties.

It seems that volunteers quickly reintegrated into American society after their war service. Many men returned to their former jobs. For example, Fead returned and again filled a position as Michigan State Judge, before being elected to the Michigan Supreme Court. For women, this was a different story. The war had facilitated an increased role of women in the public. But as the war ended, the struggle continued to make those changes permanent. With the passage of the 19th Amendment in May of 1919, many of the women listed in Streaker’s collection noted career changes and succeeded in the working world in a variety of ways [25].

Many female volunteers joined the Women’s Overseas Service League (WOSL) upon their return to the United States. WOSL was created to provide a source of support- both financial and otherwise- for female volunteers. Founded in 1921, the WOSL was a women’s “self-help group” that worked to provide an opportunity for ex-volunteers to maintain friendships forged abroad during service, sustain “a patriotic spirit” among the women, and procure aid for those wounded during their service in the war” [26]. One of the WOSL’s greatest achievements was securing access for ex-servicewomen to veterans hospitals [27]. Both the Ambulance Corps and the ARC provided opportunities for patriotic citizens to contribute to the war effort without joining the military directly. By the end of the war, these men and women had provided relief to over 4,700,000 service personnel across the world by 1918 [29]. The collaboration between the Red Cross in Ann Arbor and the students and alumni of the University abroad resulted in a significant contribution to the war relief effort from Michigan.

Notes

Please click images for full descriptions and citations

[1] Charles A. Fenton, “Ambulance Drivers in France and Italy: 1914-1918,” American Quarterly Vol. 3, No. 4 (Winter, 1951), 326-343.

[2] Roy Dikeman Chapin Papers, Box 4, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Mi.

[3] Fenton, Ambulance Drivers in France and Italy, 329.

[4] David Kennedy, Over Here: The First World War and American Society, (New York: Oxford University Press, 1980), 179-180; G. W. Osgood Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Mi.

[5] Fenton, Ambulance Drivers in France and Italy, 329.

[6] The Michigan Alumnus, vol. 25, no. 245 (Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan, 1919), 596.

[7] William Edward Votruba Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Mi.

[8] Kenneth A. Easlick Papers, Box 1, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Mi.

[9] William Edward Votruba Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Mi.

[10] G. W. Osgood Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Mi.

[11] Kennedy, Over Here, 222-223.

[12] William Edward Votruba, Kenneth Easlick, and Andrew A. Martin write poems and memoirs about their experiences. Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Mi.

[13] “World War I and the American Red Cross” American Red Cross,accessed September 30, 2015. http://www.redcross.org/about-us/history/red-cross-american-history/WWI

[14] Thursday, June 7, 1918, Journal. L. May Helmer Collection, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Mi.

[15] L. May Helmer Correspondence with Genevieve, L. May Helmer Collection, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Mi.

[16] Bess Striker, “Twenty Years Later.” Box 6, Louis H. Fead Collection, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Mi.

[17], “Letters from France” December 8, 1918. Newspaper clipping from Newberry, Michigan. L.H. Fead Collection, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Mi.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Box 1, L. H. Fead Collection, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Mi.

[20] L. H Fead to the Newberry Newspaper, December 8, 1918. Box 1, L. H. Fead Collection, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Mi.

[21] Striker, Bess. “Twenty Years Later.”

[22] Letter from L. May Helmer to Genevieve, December 9, 1917, L. May Helmer Collection, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Mi.

[23] Striker, Bess. “Twenty Years Later.”

[24] Box 1, L. H. Fead Collection, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Mi.

[25] Striker, Bess “Twenty Years Later.”

[26] “A Brief History,” Women’s Overseas Service League, accessed September 30, 2015. http://www.wosl.org/history.htm

[27] Ibid.

[28] “World War I and the American Red Cross” American Red Cross, accessed September 30, 2015. http://www.redcross.org/about-us/history/red-cross-american-history/WWI