Readying for a Fight

“Don’t reel over when I tell you. But, I enlisted last Monday...Students are enlisting here at the rate of about ten per day. It is all in the air.”

-- Rudolph Gjelsness, future University of Michigan Dean [1]

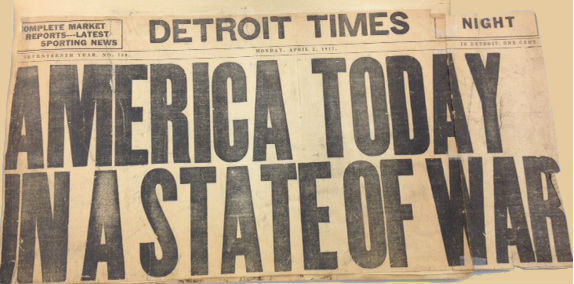

Of all the World War I materials shelved at the Bentley Historical Library, some of the most emotionally striking might be from before a single American soldier had set foot on European soil as part of the United States’ war effort. Written in thick pencil with an invariably steady hand, the enlistment cards that live in the occasional archival manilla folder don’t look unusually important; they’re nothing much beyond small rectangles of paper with a man’s name and hometown, nothing that catches the eye or gives off an air of life-changing gravitas. As the specter of the conflict overseas became a more visible presence in America, though, these cards were a tidy summation of recent history and an omen of the near future. They remain historical documents with little need for context, and even still the stoic letters handwritten across them are self-explanatory and eerie.

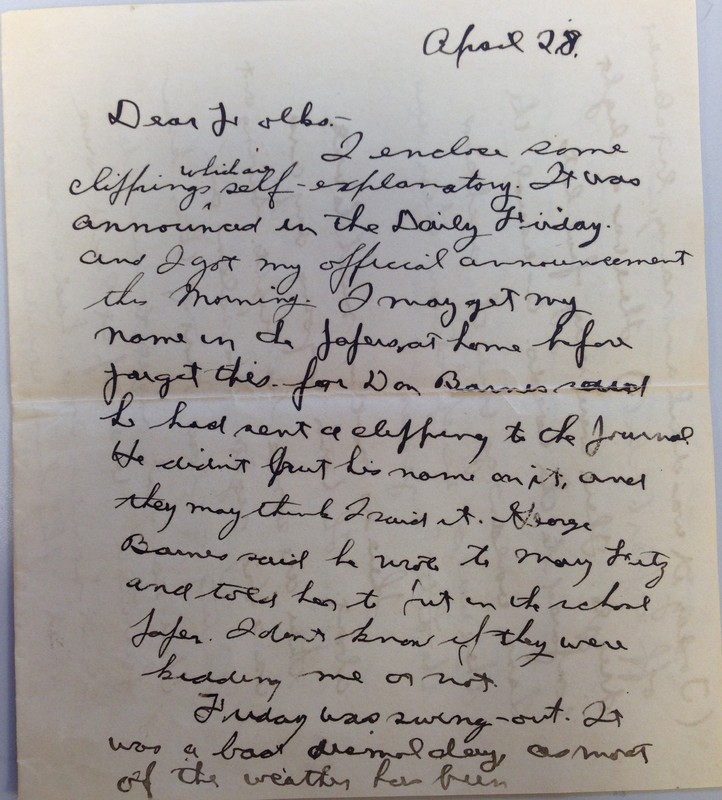

As millions of young men across the United States pencilled in their personal information on millions of unassuming government forms, what were their feelings? The historical record suggests an acceptance bordering on enthusiasm. Some historians have argued that many young Americans were enchanted by legends of the Civil War. World War I provided them with a stage to both prove their manhood and establish a heroic legacy of their own [2]. But there are limits to what historians can directly know about the events of the past, and there are corresponding moments when they need to step outside the explicit facts and make a few well-informed guesses. If one were to take students' words at face value, it might seem that many of the young men of the time were indeed eager to follow the flag into war. For example, one newly enlisted University of Michigan senior proudly wrote his parents that “I may get my name in the newspapers back home [3].” But "face value" isn’t a particularly safe investment for historians. It’s not difficult to imagine thousands of Michigan students apprehensive about their potential role in the unprecedented bloodshed of the conflict. Of the nineteen- and twenty-year-old men who fell asleep every night between Hill Street and Geddes Avenue, how many were slumbered soundly with patriotic songs filling their dreams and how many were kept awake by fears of machine guns, chlorine gas, and propaganda-shaped images of the loathsome Hun? We will never know. But through the archival materials in the Bentley Historical Library we can follow some of their journeys from student to nurse, soldier, of ambulance drivers. From the campus training ground, to regional training camps to the front.

Notes

Please click images for full descriptions and citations

[1] Rudolph Gjelsness to his mother, December 10, 1919. Box 1. Rudolph Gjelsness Papers. Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

[2] Edward A. Gutierrez, Doughboys on the Great War: How American Soldiers Viewed Their Military Experience. (Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 2014).

[3] Arthur Ehrlicher to parents, April 28, 1918. Folder 1. Arthur Ehrlicher Papers. Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.