Regional Training Camps: The Case of Camp Custer

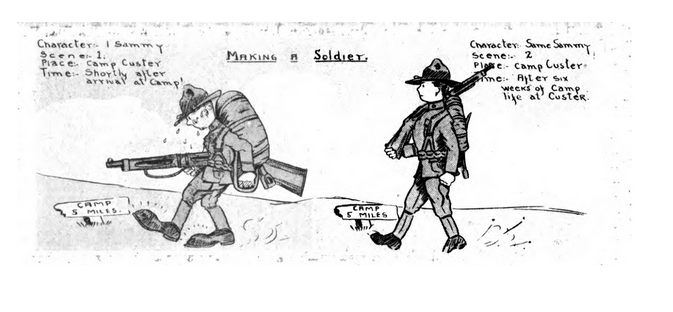

“Camp Custer -- a national university that takes the young men from the farm, the shop and the office and in a few short months graduates soldiers, trained and equipped, ready to fight the battles of democracy.”

“Camp Custer Souvenir”[1]

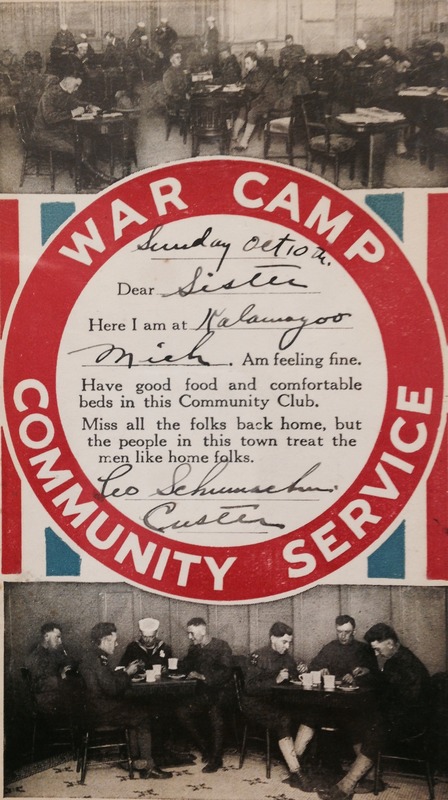

Before shipping off to Europe, enlistees and draftees alike trained at military camps across the country. Located about five miles west of Battle Creek, Fort Custer continues to be a bustling military facility. ROTC students from Michigan, Illinois, Ohio, and Indiana train there, and it remains one of the busiest centers for the Michigan National Guard. The fort, built hastily in July 1917, is almost a century old. It was originally named Camp Custer for the Michigan-raised general of Western lore and served as a training camp for newly enlisted and drafted soldiers from the region [2]. Of the students and graduates of the University of Michigan involved in the war, many were funneled through the camp on their way overseas, and the University maintained an active presence there. The Michigan Alumnus proudly reported the high percentages of Michigan students who had been named officers at Camp Custer. Moreover, university clubs from Ann Arbor regularly visited the camp to entertain enlisted men by hosting cookouts and performing operas and other vaudeville-style acts [3]. The University also extended its education to the camp, offering classes there in French, physics, chemistry, history, and international relations open to anyone interested [4]. The camp hosted nearly 100,000 men, and although initially planned for destruction following the armistice, it was put to use again during World War II and remained a permanent fixture in the Battle Creek area. The training at Camp Custer prepared soldiers not only the practical skills for battle but also instilled in them the military’s ideology. The historian Jennifer Keene wrote that “propaganda permeated the training camp as well as the home front,” arguing that letters from soldiers in places like Camp Custer were “[w]ritten under the watchful eye of the YMCA secretary...officers censored each one before sending it off" [5]. While obviously an issue of censorship, it was also a subtle reinforcement of military hierarchy that incentivize adherence to the upbeat attitude that the army pushed. Soldiers were provided free stationery and postage for cheery letters home that served to unite those on the so-called home front behind the soldiers, the country, and the cause.

The letters in the archive reflect, for the most part, this forcible cheeriness, though doubts occasionally crept in. “I am very glad indeed to be here. It is a great opportunity…The spirit of the camp is great! Every man putting his soul into it” wrote Sgt. Harry Crawford to his mother, describing the sort of gusto and patriotism at work -- real or embellished -- in the camps [6]. Frederick Clever Bald, future professor of history at UM, wrote to his parents from his camp in Georgia; complaining of the boredom and the heat, he spent his time reading H.G. Wells and participating in a football league that soldiers had organized [7]. “This hanging around is getting pretty tiresome,” wrote UM alumnus Wilfrid Haughey, a surgeon in a medical corps; “[L]ast night Major Barrett said he had actually forgotten whether he had ever operated or not, it had been so long” [8]. Another Univeristy of Michigan alumnus comforted his worried sister, writing that “[i]t won’t be so dangerous as people think...we aren’t out in front.” Fittingly, the same soldier who reassured his family may have been a little unsure of his situation himself. His first letter home from Camp Shelby in Mississippi began “‘Having a fine time. Wish you were here’” in pronounced quotation marks as if to suggest that the lines had been suggested to him by a higher-up [9]. Jennifer Keene cautioned historians against reading too literally into letters from camps for exactly this reason lest they fall for the party line parroted upon so many young soldiers.

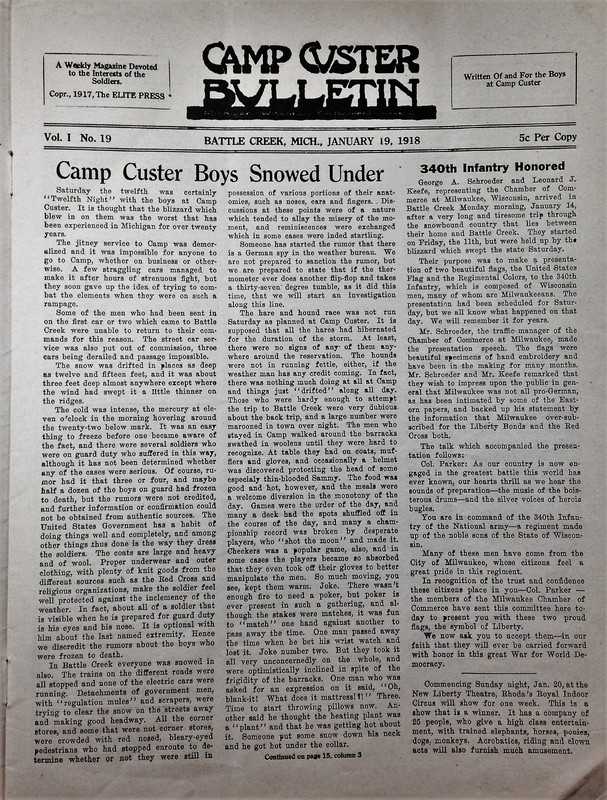

Even the military training varied in its effectiveness. Expediency was key in the wake of America’s entrance into the war, as enlistment drives fell short of expected totals and the United States faced the prospect of sending an understaffed and ill-equipped army to Europe. Though some soldiers found life at training camps dull, it wasn’t for having stayed too long. In an interview with Levi Bartel, the camp comes across as little more than a couple weeks of wasted time. “17 days -- that is all we was there…[more training] wouldn’t have done a bit of good out there...The training they had in camp here, why it didn’t mean nothing”[10]. For Bartel and the soldiers who spent a month or so playing baseball, tanning, and taking French classes, training camps hardly prepared them for what they would face once in Europe. The auxiliary amenities of camp life also provided an enticing alternative to military discipline. The local business advertised in the troop-produced Camp Custer Bulletin, offering soldiers billiards, cigars, and dance lessons [11]. William Votruba, a Michigan alumnus, trained at Camp Craig, recalled mornings filled with easy classes and simple drills. In the evening, he and his friends were free to explore the nightlife of neighboring Allentown, Pennsylvania [12]. Rather than the strict and efficient training regimen advertised, camps around the country provided only the basics of military preparation, serving mainly as a purgatory for soldiers anxious about their eventual destination.

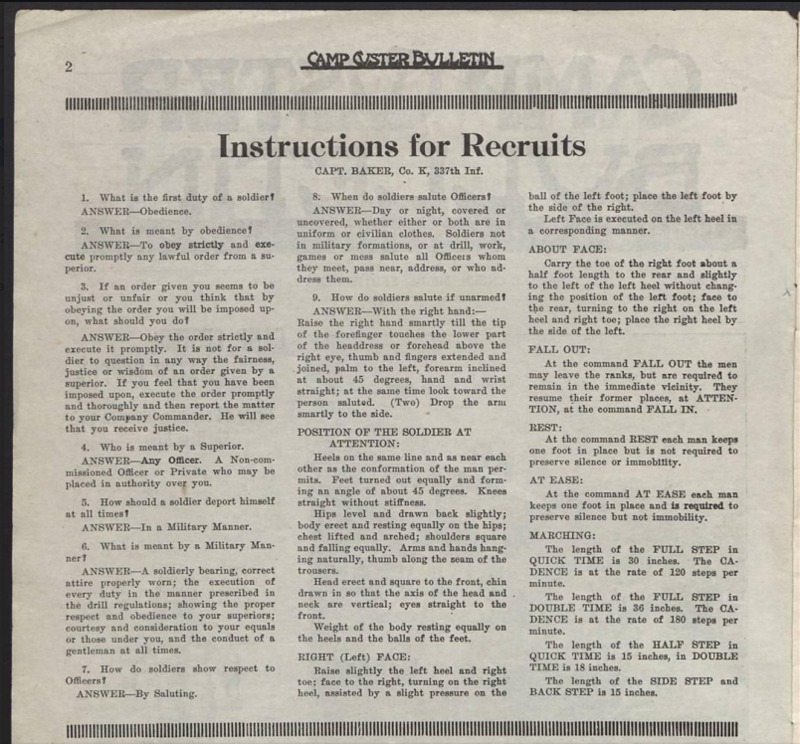

The Camp Custer Bulletin, a periodical published by the camp, gives additional insight into the mindset of those who trained there. Each edition features some articles addressing the concerns of trainees and their families. Seeking input from men at Camp Custer and those fighting in Europe, the editors of the Bulletin, worked to provide their audience with information and entertainment. The Bulletin would include Army memos, jokes, poetry, and cartoons about camp life.

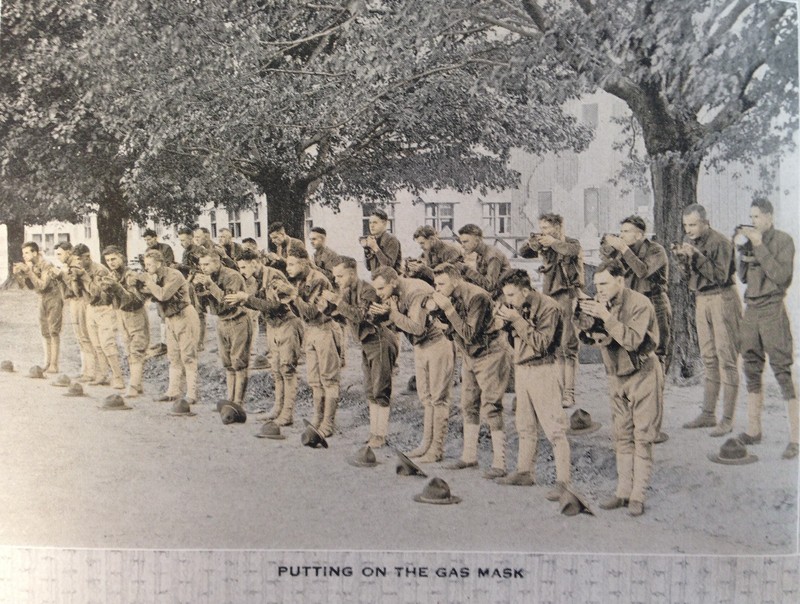

The Bulletin standardized the trainee’s knowledge for service on the front and reminded young conscripts to respect their commanding officers and observe overall military discipline. Memos from the War Department outlined the training expected of the men, describing time spent drilling, studying training pamphlets, as well as learning the French language and geography [13]. Other instructions concerned marching and defensive procedures [14] or how to groom and maintain one’s horse [15]. The Bulletin addressed personal health, with particular attention placed on oral hygiene and foot sanitation in anticipation of life in the trenches [16]. Moreover, the editors urged the men to respect their comrades and superiors. “As friends salute each other in civil life, so should officers and men engaged in the service of their country not fail to do honor to their comrades in arms” [17]. One article titled “Instructions for Recruits” was frequently reprinted. It outlined the ‘military manner by which men were to behave. Men were to have “a soldierly bearing, correct attire properly worn; the execution of every duty in the manner prescribed in the drill regulations; showing the proper respect and obedience to your superiors; courtesy and consideration to your equals or those under you, and conduct of a gentleman at all times” [18]. Soldiers were instructed to use their free time to read through the "Instruction Bulletins" posted in the Bulletin, and “all other orders and circulars of general interest [19].” The continued reprints communicated the ideals of the United States Army to a population that had not been drafted for war since the Civil War some fifty years prior.

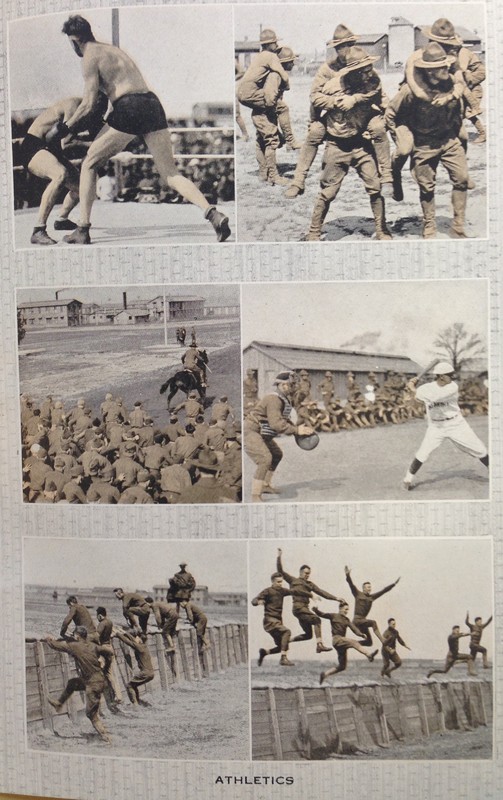

In addition to their rigorous training, the men training in Camp Custer passed their time playing sports, writing to their families and reading in the common rooms set up by the YMCA. Under the direction of Captain A.D. Newman, Athletic Director for the 85th Division, the camp administration oversaw the arrangement of different athletic events. The Bulletin reported that sports were “a very important factor in the training of the men, and a system, which will encourage competition is being worked up in order that the men can take advantage of the opportunity to prove their superiority over their comrades in arms” [20]. The 33rd Battalion notably organized a football team in 1917, comprised mostly of Native Americans from the Mount Pleasant College. The 33rd competed with other Camp Custer teams as well as other local leagues [21]. In addition to football, the men played baseball and organized wrestling and boxing competitions. Or for those uninterested in organized sports, leapfrog, tag and relay races were also reported as activities the men performed in their leisure time [22]. The Bulletin facilitated these events by posting announcements regarding games, practices, and events.

Though the Bulletin was primarily informational, it also published jokes and poetry attributed to the soldiers training at the camp. From humorous articles to one-line jokes, the lighter articles worked to provide distraction and comfort to soldiers and those waiting at home for editions alike. The poetry published in the Bulletin worked in a different way, capturing the patriotic fervor promoted by the Army camp as well as the fears and concerns the men had regarding their future in the trenches. With titles such as “When Will the Kaiser Rule The World” and “What Sort of Fellow Are You,” the poetry encourages confidence in the soldier’s skills and dedication to the cause [23][24]. Others, like “Soldiers Come Back Clean” by ‘Jackson Patriot,’ convey an assertion by the soldiers themselves that believe they are doing what is right. “I may lie in the mud of the trenches/ I may reek with blood and mire/ But I will control, by the God in my soul/ The might of my man’s desire. /I will fight my foe in the open/ But my sword shall be sharp and keen/ for the foe within who would lure me to sin, and I will come back clean.” [25] By publishing these experiences and interpretations of their experiences, the Camp Custer Bulletin provided a space where the soldiers could encourage and commiserate with their fellow trainees.

Notes

Please click images for full descriptions and citations

[1] Frank Jones, H.E. Atkins, "Souvenir, Camp Custer, Michigan," (Battle Creek: Atkins Engraving Co., 1918), 3.

[2] “The Departure of Ann Arbor’s Draft Contingent,” The Michigan Alumnus, Vol. 24 (1917), 14-15.

[3] “University Club of Battle Creek,” The Michigan Alumnus, Vol. 24 (1917), 197-8.

[4] “University Plans to Instruct U.S. Soldiers,” The Michigan Daily, October 25, 1917.

[5] Jennifer D. Keene, "Fighting the Great War: Reconsidering the American Soldier Experience," in Historically Speaking, 13 (Jan 2012), 8.

[6] Harry Crawford to his mother, undated 1917, Crawford Family Papers, Box 1, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

[7] F. Clever Bald to father, December 2, 1917; Bald to his mother, February 17, 1918, F. Clever Bald Papers, Box 1, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

[8] Wilfrid Haughey to Edith Haughey, undated 1917, Haughey Family Papers, Box 1, Folder 1, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

[9] Arthur Ehrlicher to sister, June 27, 1918; Arthur to parents, July 7, 1918, Arthur Ehrlicher Papers, Box 1, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

[10] Katheryn Johnson, "No Poppies Grow: The Formation of a Group Identity and Fighting Myth of the 339th American Regiment in the Allied Expedition to Northern Russia 1918-1919," Undergraduate Honors Thesis (University of Michigan, 2015), 20.

[11] Camp Custer Bulletin, Vol. 1 (Jan 19, 1918), 5.

[12] William Votruba memoir, Undated, William E. Votruba Papers, Box 1 Folder 3, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

[13] Wilfrid Haughey to Edith Haughey, undated 1917, Haughey Family Papers, Box 1, Folder 1.

[14] “Memo 192” Camp Custer Bulletin, January 18, 1918, 7.

[15] "Instruction in Gas Defense," Instruction Bulletin No. 1, Jan 1, 1918.

[16] Camp Custer Bulletin, January 18, 1918, 6.

[17] “Care of Mouth and Teeth” Camp Custer Bulletin, Jan 18, 1918, 6.

[18] “Headquarters 85th Division, Memorandum No. 185,” Camp Custer Bulletin, January 18, 1918, 6.

[19] “Instructions for Recruits” Camp Custer Bulletin, September 20, 1917, 4.

[20] “Instruction Bulletin No. 14” Camp Custer Bulletin, Jan 19, 1918, 13.

[21] “Capt. Newman Athletic Director” Camp Custer Bulletin, Jan 19, 1918, 5.

[22] “To Have a Football Team” Camp Custer Bulletin, September 20, 1917, 14.

[23] “Just to Break the Strain”, Camp Custer Bulletin, September 20, 1917, 14.

[24] Camp Custer Bulletin, October 4, 1917, 8.

[25] “Soldiers Come Back Clean” Camp Custer Bulletin, Jan 19, 1918, 10.

For additional photos, please check out the Camp Custer Gallery!