Regents' First Resolution for Divestment

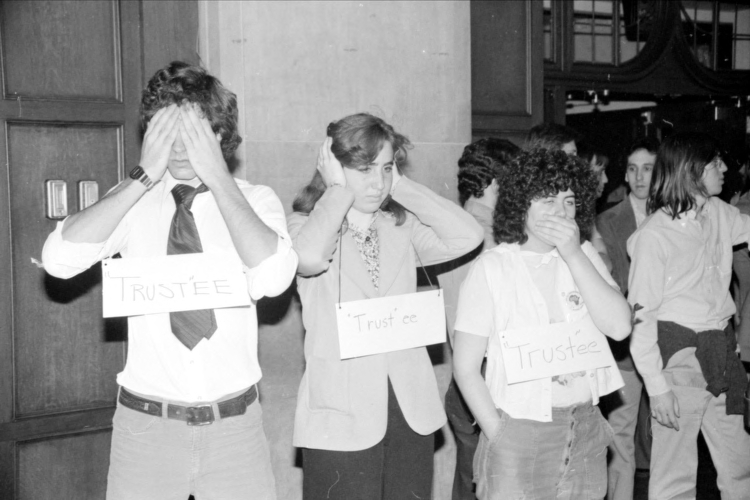

Student protests throughout 1977 and the beginning of 1978 had steadily increaded the pressure on the Regents. The Regents feared student activist movements after the Black Action Movement (BAM) of the early 1970’s caused extensive damage to University property. In addition, they were fighting against the new Michigan Open Meeting Law, attempting to preserve the option to close Board meetings to the public. However, the Regents' status as publicly elected officials caused them to lose this fight. As a result, students were allowed to protest the University’s South African ties at Regents' meetings, eventually leading to a Regents' resolution on South African investments on March 16th, 1978 wherein the University affirmed the Sullivan Principles. Despite pressure from activists, including a report from a committee composed of faculty, students, and administrators urging the regents to "liquidate University investments in businesses dealing in South Africa as soon as possible," the Regents instead voted in favor of "caution." Endorsing a report from the Senate Advisory Committee on Financial Affairs on Investment Policies and Social Responsibility, a group that represented prominent members of the University's financial apparatus, the Regents ultimately decided divestment was too radical a decision and went with the more conservative Principles.

The Resolution

In the March 16th resolution, the Regents made sure to condemn apartheid policies as "oppressive...immoral and unconscionable." Rather than divest, the Regents authorized the Vice President and Chief Financial Officer of the University to send letters to corporations UM held stock in, requesting that they adhere to three stipulations. First, corporations had to affirm the Sullivan Principles, which were already discounted by most anti-apartheid activists as a rather loose set of restrictions that wielded little power to imporove conditions. Second, the Regents urged corporations to "endorse the enhancement of political, economic and social rights" for employees in South Africa, a familiar strategy championed as an alternative to divestment that activists roundly criticized as ineffective. Finally, the Regents asked for "regular" reports from corporations on their progress in these areas. Additionally, the resolution stated that the University would withdraw deposits from banks that increased loans to the South African government, but tempered this commitment by allowing such banks to demonstrate that "such loans [were] conditioned upon governmental action which shall tend to end the system of apartheid." If any corporation did not, "within a reasonable period of time take reasonable steps" to adhere to the resolution, the Regents promised to divest from those corporations. However, this ultimatum rang hollow for anti-apartheid activists, as it failed to establish any measurable standards by which to make such a decision.

Therefore, the Regents resolution successfully condemned apartheid rhetorically without taking any concrete steps toward divestment. For many members of the University of Michigan's anti-apartheid movement, this action by the Regents was "wholly insufficient" and invited further pressure on the Regents in the future. In The Michigan Daily, Heidi Gottfried commented that the resolution "showed a complete disregard" by University leaders for "the views of the University community." Many in the University community were unsatisfied with the Regents’ March 16th resolution and adoption of the Sullivan Principles. On March 22nd, 1978, the Executive Council of the LS&A Student Government passed this resolution opposing the Regents’ decision and calling for total divestiture. The resolution reports that 18 students, faculty, and Ann Arbor citizens spoke in support of divestment at the March 16th Regents meeting and that 200 protesters were in attendance. This suggests that the divestiture movement was growing and becoming a prominent issue on campus. The resolution uses language that is harshly critical of both the Regents and the Sullivan principles. This use of passionate language by a mainstream campus organization shows that the anti-apartheid movement was starting to resonate with the wider student body.

While many activists fully opposed the Sullivan Principles, the Regents' adoption of them made the divestment debate more complicated and multifaceted. In a 2015 interview, Debi Duke, a key member of the WCCAA, describes how the Sullivan Principles created rifts within anti-Apartheid groups on campus,

I believe WCCAA split, and certainly campus liberals and progressives were divided, once the Sullivan Principles were put on the table. I was part of the group that believed strongly in the need to oppose and expose the Sullivan Principles. We felt that the regents and others in power used the Principles simply as an excuse not to divest and that individual members were either thoroughly on the wrong side (even evil) or weak and unprincipled. I was somewhat disillusioned by this--I expected it from corporate leaders, but thought the leaders of great universities would somehow be “better.”

Taking Action?

Following the passage of the March 16th resolution, the University began sending letters to companies and banks that the school owned stock in or had accounts with. While the letters state “the University is strongly opposed to apartheid” and considers it “immoral and unconscionable,” the Regents did not want companies to stop doing business in South Africa. Although they acknowledge that there were “many members of the University demanding that the University sell its shares in corporations doing business in South Africa,” the Regents maintained that the companies could be a “positive force” in the country. The University asked these corporations to uphold the Sullivan Principles but were forced to rely on the companies’ own reports of their compliance. The letters close with the school saying they would appreciate any reports or comments the companies think would be helpful.

This report from October 1978 summarizes the results of the letters and questionnaires the University sent to companies regarding the Sullivan Principles. While most companies submitted responses, a few refused or simply did not respond. Some banks said “that the Regents are not entitled to know if the bank is doing business with a client or the nature and extent of the relationship.” The report goes on to outline the difficulty of obtaining information about the activities of banks and companies who failed to respond. Although several colleges and universities with investment resolutions similar to the University of Michigan’s created a center to analyze U.S. corporate activity in South Africa, voluntary questionnaires from companies remained a key part of their data surveillance system. As the inadequacies and shortcomings of the Regents’ resolution became clear, student activists became even more vocal in their opposition to it. A year after the passage of the 1978 resolution, this would lead to an even bigger confrontation between the activists and the University’s administration.

Sources for this page:

The Regents of the University of Michigan, "Resolution: The University of Michigan Board of Regents, March 16, 1978," Regents Meeting, March 16 and 17, 1978, Box 144, University of Michigan Board of Regents Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

The Michigan Daily, February 18, 1978

The Michigan Daily, March 16, 1978

The Michigan Daily, March 18, 1978

The Michigan Daily, March 19, 1978