Bullard's Bills

Starting in the late 1970s, anti-apartheid activists in Michigan began pressing both federal and state lawmakers for legislative action against South Africa and the American corporations that invested with the apartheid regime. In early 1978, the Michigan state legislature passed a resolution urging the U.S. Congress and President Carter to impose economic sanctions against the South African government. The decree, sponsored by Jackie Vaughn, an African American representative from Detroit, condemned the apartheid government for arresting political dissidents, violating freedom of speech, and in general operating with “disregard for human rights and dignity.” The Detroit-based United Auto Workers also called on the Carter administration to curb U.S. government and corporate support for South Africa’s “racist, repressive, and undemocratic” policies, in particular its ban on trade unions for black workers. David Gordon, a political scientist at the University of Michigan and a member of the campus-based Committee on Southern Africa, warned the Carter White House that “it is urgent for the United States to put pressure on the Pretoria regime and to begin to withdraw the financial, moral and political support that the American corporate presence brings to the South African government.” Gordon explained that while U.S. corporations might not “prefer the Apartheid system,” foreign investment provided the “economic underpinning” and Black South Africans “overwhelmingly view business efforts as anti-liberation and pro-government."

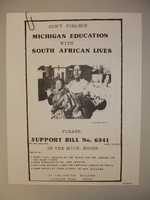

At the state government level, Democratic Representative Perry Bullard of Ann Arbor worked closely with anti-apartheid organizations such as the Washtenaw County Coalition Against Apartheid (WCCAA) to pass legislation that would force universities and corporations based in Michigan to divest from South Africa. Almost every year between 1978 and the mid-1980s, Bullard introduced multiple bills to require divestment by the state government, pension funds, financial institutions, and public universities. Bullard, a white progressive with roots in the anti-Vietnam War movement, often co-sponsored legislation with state senator Virgil Smith, an African American Democrat from Detroit and the head of the Black Caucus. During the late 1970s, Bullard and Smith circulated flyers with images of the Soweto massacre urging Michigan voters to demand divestment, with the slogan “Don’t Finance Michigan Education with South African Lives.” A major political breakthrough came in 1978, when campus and community activists in East Lansing convinced the Board of Trustees of Michigan State University to divest from corporations with holdings in South Africa, despite Dow Chemical’s threat to withhold donations from the institution.

One year later, Robert Stechuk, the LSA student government president at the University of Michigan, urged the state legislature to “require withdrawal from South Africa by law.” Stechuk rejected the Board of Regents argument that American corporate investments had a moderating effect on the apartheid system, instead emphasizing that divestment would force the South African government to choose between the “industrially productive and the brutally oppressive.”

Following MSU’s divestment, attention turned to forcing the divestment of other Michigan colleges and universities. The University of Michigan, the state’s other major university and holder of more than $50 million in South Africa-related stock, received much of the focus. In 1980, Bullard sponsored three bills aimed at preventing public funds from being invested in companies doing business in South Africa. The bills would force the divestment of public pension funds, public universities, and financial institutions that received state government deposits. The UM and MSU student assemblies, religious groups, and labor all supported the bills. The Michigan Manufacturers’ Association lobbied against the legislative package, as did General Motors and Ford Motor Company, each of which had major investments in South Africa. In response, Bullard began circulating fliers urging voters to contact their state representatives and senators and “voice your support to fight apartheid in South Africa.” The fliers explained the apartheid system and the reasoning behind the divestment campaign.

At Michigan, the WCCAA became very involved in promoting the bills. They circulated petitions and wrote letters urging people to contact their state representatives. A member of the Coalition’s Steering Committee wrote a Michigan Daily editorial telling students that "the bills have nearly enough support to pass" and urging them to contact representatives to secure their passage. He argued that "as long as US firms remain, their capital, technology, and products will be directed by the regime against 18 million South African blacks" and that in the time it took to read his editorial, "six South African blacks have been arrested for passbook violations." Bullard further courted student support by writing to Presidents of student governments and the editors of student newspapers. In his letter, he highlighted the important role of student activists in the successful divestment of MSU and anti-apartheid campaigns across the nation. The letter shows the diverse base of the anti-apartheid movement when Bullard calls for students, churches, labor, and civil rights groups to unite in support of the bills. Ultimately, two of the three bills would fail. Only the bill divesting financial institutions of state funds would pass in late 1980. Divestment of the state’s universities had to wait for another push.

UM Begins to Formulate its Defense

UM administration officials resisted Bullard’s educational divestment bill and explained that while they did not endorse apartheid, the university had the right to invest in corporations that adopted the Sullivan Principles. In 1982, Regent Thomas Roach, a bank executive, countered the growing campus support for divestment by agreeing that “apartheid is abhorent in a civilized world” while asserting that the American business presence would influence South Africa “to share the fruits of its political and economic system.” The looming possibility of a legislative ban prompted UM leaders to make a second argument based on the legal grounds of institutional autonomy. The UM defense centered on the provision in the Michigan state constitution that governing boards of public universities had full legal authority to the “general supervision of its institutions and the control and direction of all expenditures from the institution’s funds.” Just in case, the University of Michigan lobbied the state legislature to include a Sullivan Principles exemption in any legislation that required divestment by educational institutions. By the end of 1982, University of Michigan investments in corporations with ties to South Africa had reached $70 million, with the largest holdings in Southeast Michigan-based corporations General Motors and Ford Motor Company. The list included many other blue-chip corporations: Dow Chemical, Xerox, Pfizer, Bristol-Myers, Texaco, General Electric, Kraft, Caterpillar, and dozens more. An audit later revealed that of the forty-six such corporations in which UM held stock, thirteen were in compliance with the Sullivan Principles, ten were in direct violation, and twenty-three were “uncertain or evasive.”

The University of Michigan’s defense of the Sullivan Principles and its legal right to investment autonomy drew fierce criticism from anti-apartheid activists as the state legislature considered the divestment legislation. Perry Bullard, the bill’s sponsor and UM’s direct representative in the legislature, denounced the anti-divestment forces as “agents of the South African government, Ford Motor Company, and a University which will remain nameless.” Bullard explained to members of the legislature that the Sullivan Principles “deliberately obscure the basic issues of human dignity and political freedom” and “have been cleared as ‘acceptable’ by the South African government because they are not seen as a threat to the apartheid system.” In another memo, Bullard harshly criticized the University of Michigan for pretending that corporate investment would improve discrimination against Black South Africans when the “University has exerted no such leverage whatsoever” and instead defended policies that “favor the status quo of racial segregation and virtual slavery.” The Washtenaw County Coalition Against Apartheid also rejected UM’s position that a state divestment mandate infringed on its constitutional autonomy and concluded: “Do not be fooled by the Regents’ arguments. The state legislature has the power . . . to order divestment by universities of investments in companies doing business with the racist South African regime." Soon, the legislature would act on that power and the Regents would have to decide how to react.

Sources for this page:

The Michigan Daily, March 22, 1980

The Michigan Daily, March 23, 1980

The Michigan Daily, May 29, 1982

University Record, April 11, 1983.

Janice Love, The U.S. Anti-Apartheid Movement: Local Activism in Global Politics (New York: Praeger Publishers, 1985)

House Concurrent Resolution No. 462, “Sanctions Against the South African Government,” February 6, 1978, Folder MSU-S.A. Background Report 1979, Box 24, Perry Bullard Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

United Auto Workers, Press Release, March 3, 1978, Folder MSU-S.A. Background Report 1979, Box 24, Perry Bullard Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

David F. Gordon, “U.S. Policy and South Africa,” December 13, 1979,” Folder UM + SA Materials 1981, Box 24, Perry Bullard Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

“Don’t Finance Michigan Education with South African Lives,” Sept. 20, 1978, WCCAA Michigan House Bills for Divestment 1978-1980, Box 5, Center for Afroamerican and African Studies Records, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

Robert A. Stechuk, Testimony before the Michigan State Legislature Standing Committee on Civil Rights, November 27, 1979, Folder Lobbying Material, Box 25, Perry Bullard Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

"Voice Your Support to Fight Apartheid in South Africa” Box 24, Perry Bullard Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

WCCAA Steering Committee form letter, March 15 1980, WCCAA South Africa and Divestment 1979-1980, Box 5, CAAS, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

Perry Bullard form letter to Presidents of student government and news editors, March 31 1980, WCCAA Michigan House Bills for Divestment 1978-1980, Box 5, CAAS, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

Perry Bullard, Hand Out for Senate Floor, n.d. [December 1982], Folder Materials Related to Sullivan Amendment, Box 25, Perry Bullard Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

Perry Bullard to Michigan State Senators, December 7, 1982, Folder Materials Related to Sullivan Amendment, Box 25, Perry Bullard Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

Washtenaw County Coalition Against Apartheid, “The South Africa Divestment Law Is Constitutional,” February 14, 1983, Folder News Clippings—State of Michigan and Divestment, Box 24, Perry Bullard Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

Perry Bullard to Michigan State Senators, December 7, 1982, Folder Materials Related to Sullivan Amendment, Box 25, Perry Bullard Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

Regents of the University of Michigan, "Compliance data," April 14, 1983, p. 652, Proceedings of the Board of Regents, April 1983, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan