Broader Legacies and Conclusions

Broader Legacies

Curiously, the anti-apartheid movement, especially in the U.S., has perhaps not received sufficient recognition for its contributions to the activist tradition. Though perhaps never as vehement or widespread as well-known movements such as the anti-Vietnam War movement or the civil rights campaigns of the 1960s and 70s, anti-apartheid efforts represent a key transition from such past movments toward the future. Inheriting the lessons from civil rights protest, strategies for economic sanctions, and campus initiatives such as the Free Speech Movement, anti-apartheid activsts brought together powerful currents of strategy and tradition to create a modern, distinctly multicultural movement that extended its influence internationally.

For David Hostetter, the American civil rights struggle was crucial for anti-apartheid action, not only as a model for protest, but as a standard of moral solidarity along racial lines. The many different groups that participated in the push for divestment at the University of Michigan exemplify an historic step in the integration of activist movements in the U.S., which "extended the ethos of the civil rights movement into the area of foreign policy." Throughout the process of achieving its goals, the movement connected human rights struggles around the world with previously domesticated issues surrounding civil rights. This helped give rise to future global movements, such as anti-sweatshop action, that relied on similar moral and multi-cultural foundations and advanced the issue through advocacy for economic policy shifts.

Conclusions

Thus, the anti-apartheid movement at the University of Michigan deserves recognition as a crucial moment in the University’s history. For a dedicated group of student, faculty, and community activists in Southeast Michigan, the challenges and complexities of their particular struggle were considerable. Their ultimate goal was to bring an end to a set of brutal, racist policies that had withstood decades of resistance, both in South Africa and around the world.

In contrast to the social movements that dominated previous decades, such as the civil rights movement of the 1960s and 70s, and the protest movement against the Vietnam War, the target was not domestic policy, but the policies of a foreign government bearing no legal obligation to respond to the outcry of the American people. Within the context of a larger campus, and eventually mainstream political movement, University of Michigan anti-apartheid supporters lent their collective voices to a coalition of global citizens intent on confronting injustice, regardless of international boundaries. In this way, the anti-apartheid movement at UM participated in crafting a new form of global activism that remains a powerful and inspiring force today.

Perhaps equally important were the methods the movement employed. International protests against apartheid policies had always utilized varieties of economic sanctions, such as boycotts. However, the large-scale, institutional divestment campaigns of the 1970s and 1980s extended the clout of these economic measures in two important ways.

First, institutions such as the University of Michigan wielded the financial might to inflict extensive economic damage through divestment, to the tune of tens of millions of dollars. In conjunction with other large institutions with similar assets, the swiftness and scale of such an economic statement could be potentially crippling for any government that depended on international investment and trade.

Secondly, divestment campaigns raised essential moral questions about the responsibilities inherent in economic markets. Similar to previous outrage at the University of Michigan over Dow Chemical’s production of tools for war and destruction during the Vietnam War, UM’s anti-apartheid activists challenged the University to consider the moral implications of their investment practices, rather than focusing on monetary value alone.

Because the University’s financial stake in South Africa was predominantly wrapped up in stocks in companies doing business there, this moral challenge necessarily extended to the corporations who drew profits from their cooperation with the apartheid system. In Michigan, the health of the state’s finances was intimately related to the profitability of giants like Ford, General Motors, and Dow Chemical. In this way, not only did activists at UM call upon the University to use its portfolio to support moral causes and root out injustice, but they also hoped to force private enterprise to accept a driving goal besides the profit motive. This radical assertion of the ethical responsibilities of corporations is still an essential facet of protest movements, both global and local, today.

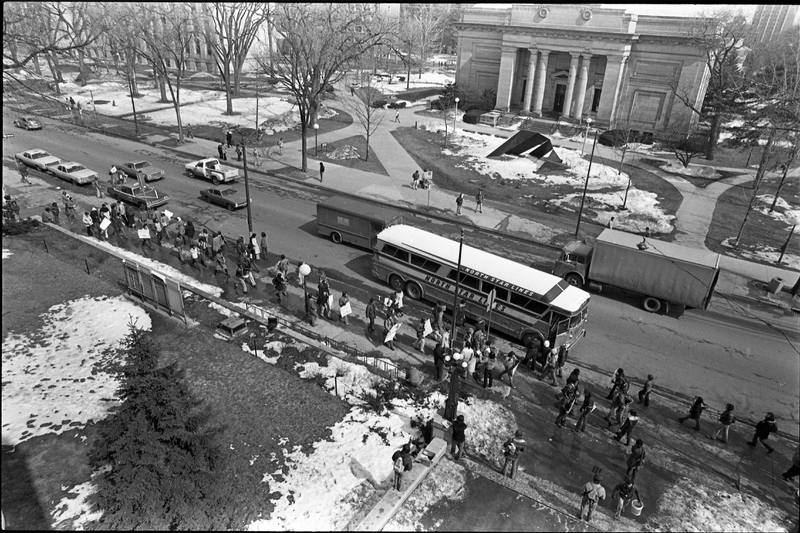

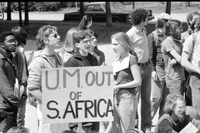

In order to advance the adopted method of using economic sanctions to influence foreign policy, activists at UM and across the country conducted a prolonged campaign that inherited the lessons and strategies of previous movements. Methods honed during the civil rights movement and the anti-Vietnam War movement, including consciousness-raising efforts and direct action tactics, allowed activists to assert their voice on campus. From SALC to the WCCAA, and finally through UCAR and the FSACC, students and faculty brought in speakers and worked through the media to inform the community of the problem at hand. Activists sat-in, taught-in, worked the picket-line, marched across campus, and brought their passionate arguments to Regents meetings, all in order to collectively demand that the University take action against such clear and present injustice. Symbolic statements, from vigils to remember the horrific events in Sharpeville and Soweto, and shantytowns to physically represent the suffering of those afflicted by apartheid, were powerful and creative manifestations of the pain of apartheid, and helped instill the moral outrage necessary to force policy changes.

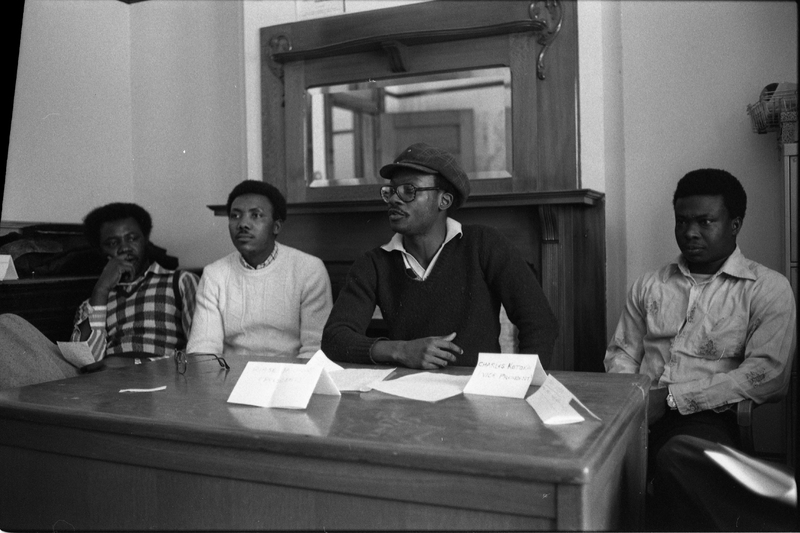

Finally, a defining aspect of the anti-apartheid movement at the University of Michigan was its commitment to inclusiveness. A policy inherent upon assumptions of racial hierarchy, the issue of apartheid necessarily required activists to confront racial inequality, both in South Africa and in the U.S. As Matthew Countryman asserted in a February 2015 interview, anti-apartheid activism gave the country a new opportunity to address the lingering racial divisions that the civil rights movement could not completely solve. During the 1970s and 80s, anti-apartheid support was one cause within a larger protest community on campus. Just as many students are involved in various causes today, the activists of anti-apartheid era flowed between causes, symbiotically supporting the efforts of others. This atmosphere, and the particular characteristics of apartheid, contributed to an incredibly diverse range of groups that lent their passion and support to anti-apartheid activities.

This multi-ethnic, multi-national coalition of activists, united by their sense of racial injustice and moral outrage, combined the characteristics and demographics of past movements like never before. Acting as this crucial bridge between previous movements and the global movements of today, such as anti-sweatshop activism, the anti-apartheid movement at the University of Michigan contributed to a realignment of national attitudes and the paradigms of protest to secure the rights of humanity as a whole.

Sources for this page:

David Hostetter, Movement Matters: American Antiapartheid Activism and the Rise of Multicultural Politics (Routledge, 2009)