Campus Anti-Apartheid Movements Intensify after Soweto

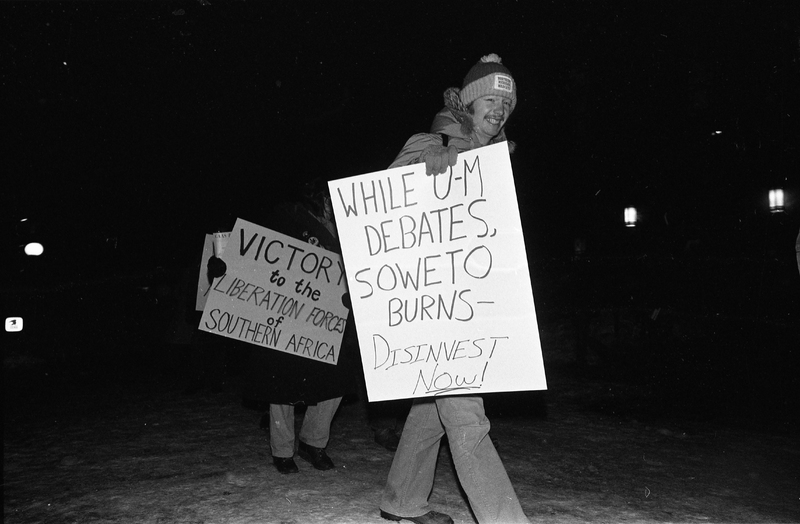

As news of the Soweto Uprising reached college campuses in the United States, many students were outraged at the violent response of the South African government. Campus anti-apartheid organizations, which had been promoting discussion and organizing small-scale protests for a decade, began to shift toward more direct forms of protest. They soon embraced a strategy first promoted by national religous and civil rights groups--a divestment campaign to pressure American corporations to withdraw economic support for the South African government. Divestment advocates on campus sought to exert pressure on American companies through the stock investments that colleges and universities owned. In the post-Soweto period, campus activists began organizing new coalitions, investigating the financial ties between their institutions and South Africa, educating students about the apartheid system, and recruiting more students to the cause. The above image demonstrates the important symbolism of Soweto in the growth of the divestment movement at the University of Michigan, as does the publicity for this January 1978 demonstration. In the document to the right, an ad-hoc coalition of UM anti-apartheid groups denounced the administration for inviting the South African ambassador to speak on campus and argued that there was "nothing to debate with the murderers of Steven Biko and Soweto militants!"

Note: the rest of this page focuses on the origins of the post-Soweto divestment campaign at other American universities during 1976-1978. The simultaneous events at the University of Michigan are covered in Section II of the Exhibit.

Stanford University

The campus anti-apartheid movement began the divestment campaign in the spring of 1977, with the first major event happening at Stanford University. Student activists created the Stanford Committee for a Responsible Investment Policy (SCRIP) to pressure the administration to support divestment resolutions introduced by national religious organizations active in the anti-apartheid cause, especially the Interfaith Council for Corporate Responsibility. When Stanford abstained from voting on the resolution to withdraw Ford Motor Company from South Africa, SCRIP staged a sit-in protest on May 10. Police arrested 294 students who refused to end their sit-in, and the episode garnered national attention and spurred the growth of the national campus anti-apartheid movement. The Michigan Daily covered the Stanford story for several days, and links between activists at Stanford and UM quickly emerged. When SCRIP activists traveled to Michigan to speak at a Ford stockholder meeting, UM student Phillip Lewis joined the group and read a statement arguing that Ford had a "moral obligation" to stop supporting the "racist and murderous political, social, and economic policies of the Republic of South Africa." Just a few weeks after the Stanford demonstration, anti-apartheid leaders from several UM student groups appeared before the Board of Regents for the first time to call for divestment from corporations operating in South Africa.

After the arrests at Stanford, divestment protests soon appeared at colleges and universities across the country. In addition to UM, students at Amherst, Columbia, Cornell, Harvard, Minnesota, Ohio State, Princeton, the University of California system, Wesleyan, and Wisconsin all staged demonstrations. In June 1977, the Stanford activists created the South Africa Catalyst Project with the goal of assisting in the creation and expansion of anti-apartheid groups on campuses across the country. The Catalyst Project and other organizations, including the American Committee on Africa, supported the growing national movement.

University of California at Berkeley

In the fall of 1977, a New Left-inspired group at UC-Berkeley published a 58-page pamphlet to expose the connections between their university, American corporations, and the South African government. Activists from the group, called Campuses United Against Apartheid (CUAA), linked the anti-apartheid campaign to the legacies of the anti-Vietnam War movement, the ongoing struggle for civil rights inside the United States, and the global struggle against imperialism and colonialism. In the opening pages, the CUAA pamphlet detailed how most of the Regents and more than two dozen Berkeley administrators and professors served as board members or executives of corporations with investments in South Africa. The U-C Regents, according to CUAA, represented "only one special interest: the interest of corporate wealth." In "The Case for Divestment" (pp. 11-15 of the pamphlet), the CUAA disputed the corporate stance that investment in South Africa would be a "force for constructive change" as a smokescreen for policies that almost exclusively benefited the "privileged white minority." In the "UC in South Africa" section (pp. 15-18), the CUAA argued that by refusing to divest, the Regents were "taking an active role in maintaining and strengthening the racist apartheid system" and "profiting from the crutal exploitation" of the nonwhite majority. Elsewhere the pamphlet expressed support for South African liberation organizations and endorsed the ANC position that "It is not enough to grant higher wages here, better conditions there, for this leaves the apartheid system intact, in fact, it props it up longer--the very source of our misery and degradation." Citing the Soweto Uprising as an inspiration, the CUAA made its slogan clear: "U.S. Corporations Out of South Africa Now!"

Michigan State University

Since its founding in 1973, the Southern Africa Liberation Committee (SALC) at Michigan State University had worked tirelessly to spread awareness of apartheid and had played a key role in promoting the divestment strategy. SALC began to secure changes in public policy in the aftermath of the Soweto Uprising, including the resolution passed by the city council of East Lansing in August 1977, prohibiting municipal contracts with suppliers who operated in South Africa. In March 1978, SALC and other anti-apartheid activists on campus convinced the Board of Regents of Michigan State University to adopt a policy of "prudent divestiture" of stock holdings in corporations that continued to operate in South Africa, one of the first such resolutions by a major American university. The policy affected about $10 million in MSU investments, including in Michigan-based corporations Dow Chemical, General Motors, and Ford Motor Company. David Wiley, the director of MSU's African Studies Center and a faculty-activist, also started working with state representatives Perry Bullard and Virgil Smith to craft anti-apartheid legislation. In 1978, the Michigan legislature passed a resolution urging the U.S. Congress to impose economic sanctions on South Africa, the forerunner to a series of divestment laws that the state government would enact in the early-to-mid 1980s.

By the spring of 1978, when MSU Regents voted to begin the divestment process, only six American instutions of higher learning had completely divested from corporations that operated in South Africa: three public universities (University of Wisconsin, Ohio University, University of Massachusetts) and two small liberal arts colleges (Antioch and Hampshire). Seven other colleges and universities, including The Ohio State University, had adopted partial divestment policies targeting specific corporations by the end of 1978. As the divestment movement threatened their interests, American corporations sought a compromise solution through the Sullivan Principles, which pledged nondiscriminatory policies toward South African workers but maintained economic ties to the apartheid regime. Many educational institutions, including the University of Michigan, embraced the Sullivan Principles as a responsible balancing act that signaled opposition to apartheid while preserving their corporate investments. This approach did not satisfy the American anti-apartheid movement, leading to an escalation of divestment confrontations on many campuses.

Sources for this page:

The South Africa Catalyst Project, Anti-apartheid organizing on campus ... and beyond (Palo Alto, Calif.: The South Africa Catalyst Project, 1978).

Janice Love, The U.S. Anti-Apartheid Movement: Local Activism in Global Politics (New York: Praeger, 1985).

Marc Fisher, "The Second Coming of Student Activism: Showdown over South Africa," Change (Feb. 1979), 26-30.

William Minter, Gail Hovey, and Charles Cobb Jr, eds., No Easy Victories: African Liberation and American Activists over a Half Century, 1950-2000 (Trenton, New Jersey: Africa World Press, 2007), <http://www.noeasyvictories.org>.