UM's 90 Percent Solution

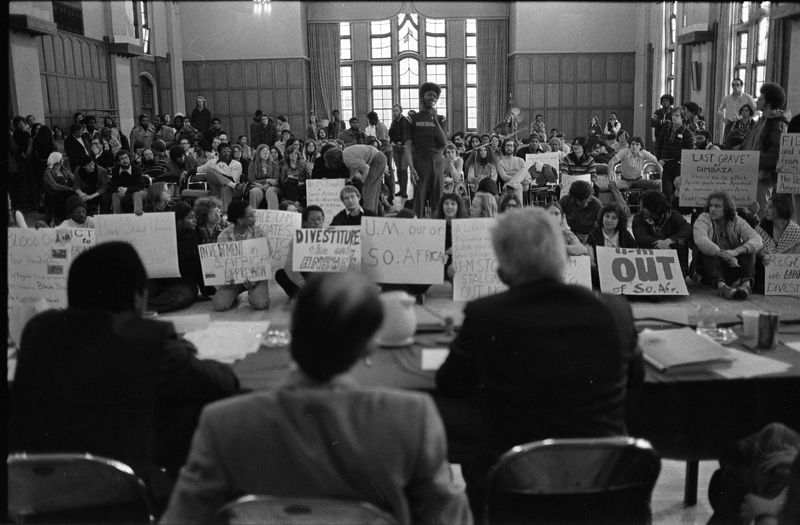

On April 14, 1983, the Board of Regents approved a compromise resolution that pledged compliance with the divestment law, Public Act 512, with the exception of corporations either headquartered in Michigan or with a significant workforce in the state. The resolution singled out four Michigan companies--Ford, General Motors, Dow Chemical, and Kellogg--for their “good faith efforts” and “courageous actions” to improve the status of Black South Africans. It then declared that despite economic improvements, “progress to end apartheid has been too slow,” especially in the area of political discrimination. And so, in the so-called “90% Solution,” the board directed the UM administration to divest (on a “financially prudent” timetable) from all American corporations with operations in South Africa except for those with a notable economic presence in Michigan. Profits from stocks and bonds in these exempted corporations would be dedicated to “programs intended to promote educational opportunities related to South Africa.” After a lengthy debate (included along with the resolution in this document), the regents voted 6-2 in favor of partial divestment. Regent Dunn, the resolution’s sponsor, declared that “we tried the Sullivan Principles for five years and…they just did not work.” Regent Varner criticized the distinction between Michigan-based and non-Michigan companies, arguing that all of them were in South Africa to “make profits” and “exploit the black population.” Regent Baker, an outspoken critic of divestment, labeled the state law an “anti-business” policy and praised Ford, GM, and Dow Chemical for having “led the way to progress for minorities in South Africa.” In its editorial response, the Michigan Daily blasted the regents for placing UM’s economic self-interest and corporate alliances over the moral crusade against apartheid, dismissing the “90% Solution” as “little more than appeasement, rather than full-fledged support, of the principles behind divestment.”

In conjunction with their divestment vote, the Board of Regents immediately passed a second resolution authorizing a lawsuit to challenge P.A. 512 as an “unconstitutional intrusion upon the powers and the authority of the Regents to direct expenditures of the University’s funds.” Regent Baker, the sponsor of the litigation resolution, categorized apartheid as an “evil institution” but strongly lambasted the state legislature for, in effect, declaring that “American business is immoral.” Baker also alleged hypocrisy by the majority on the Board of Regents for giving in to the political pressure to divest while accepting donations (most recently, a new engineering building) from Dow Chemical and other American corporations. Regent Roach, another vocal critic of divestment, compared P.A. 512 to McCarthy-era attacks on academic freedom and warned that in the long view of history, the matter of whether the legislature or the Regents controlled the University of Michigan would prove more important than the present focus on apartheid in South Africa. With its 5-3 vote to initiate the lawsuit, the board set itself on a collision course with both the legal authority of the state legislature and the grassroots power of the anti-apartheid movement, since neither partial compliance nor partial divestment would satisfy either.

The Regents’ Argument

From the time P.A. 512 passed in the Michigan Legislature, the University began quietly exploring the possibility of a legal challenge. In this confidential memo from March of 1983, UM Vice-President Brinkerhoff outlines some of the steps UM’s legal team is exploring. Brinkerhoff explains that the Regents’ resolution will have to contain certain provisions in order for the University to “retain a strong legal position” for the court case. The memo also contains the beginnings of the “90% Solution.” Brinkerhoff reports that the Regents resolution will have maintain some of the existing stockholdings to form the basis of the court case. Also, the memo shows that UM was prepared for a long fight. Brinkerhoff explains “the fastest move through Circuit Court, Court of Appeals, and Supreme Court would be two to two and a half years.”

The cornerstone of the University of Michigan’s case against Public Act 512 was an argument based on the autonomy and freedom of colleges and universities outlined in the state constitution. UM officials began outlining this argument in the months leading up to their April 1983 resolution. Regent Roach, a Democrat, argued in a February 1983 Michigan Daily article that the state should not have control over the investments of a public university, “The Regents (are) not subservient to the Legislature or anyone…The University can’t allow Lansing to dictate our policy.” Even before Governor Milliken had signed the bill, University officials voiced their intentions not to comply. Roach’s colleague, Gerald Dunn, a Democrat from Lansing and consistent supporter of divestment, accused the legislature of hypocrisy, pointing out that the state’s massive retirement fund was left undivested. Some of the Regents continued to discourage divestment as the best alternative to combat apartheid, arguing that it was an ineffective “one-time shock” and would not sufficiently injure the apartheid regime, but might negatively affect Michigan’s struggling economy.

The WCCAA and other anti-apartheid activists continued to push back against the Regents assertions that P.A. 512 was unconstitutional and violated the University’s autonomy. This 1983 flyer from the WCCAA entitled “The South Africa Divestment Law is Constitutional and Does Not Infringe on the University’s Autonomy” uses the State of Michigan’s constitution to argue against the Regents’ stance. While they acknowledge that the state constitution does say the Regents have autonomous control of the University, they quote another part of the state constitution that says, “endowment funds created for…educational purposes may be invested as provided by law governing the investment of funds.” They interpret this to mean that the legislature can make laws regarding university investments. Another important part of the argument they present draws on an earlier legal decision made by Attorney General Frank Kelley. An October 1980 opinion on an earlier case concerning university investments stated that higher education institutions can be subject to “legislative exercise of the police power” without violation of autonomy. From this, the WCCAA concluded that “if one law governing investments by universities can be enforced without violating their autonomy, then the South Africa divestment law can be as well.”

Regents v. Michigan

The Regents of the University of Michigan v. the State of Michigan was heard in the Ingham County Circuit Court by Judge Caroline Stell. The University and state’s lawyers would continue to debate the law before the Circuit Court until August of 1985. In the end, the court ruled in favor of the state and against the Regents' challenge. The crux of this decision rested on diverging definitions of "investment" and "expenditures," as the court asserted that University "investments" were not implicated by Public Act 512, but rather "expenditures." This was a remarkably weak argument for many experts, but the Regents had already decided to appeal if the decision went against them. After a two-year process, a resolution seemed distant and the Regents continued to emphasize the importance of protecting the University's autonomy, regardless of issues surrounding apartheid. The appeals process lasted a few more years, passing through the Court of Appeals and the Michigan Supreme court and included another partial divestment, before finally being decided in 1988. While the legal challenges slowly worked their way through the court system, large-scale student protests reignited on UM’s campus.

Sources for this page: (individual document citations are on the full source pages):

The Michigan Daily, January 5, 1983.

The Michigan Daily, February 1, 1983.

The Michigan Daily, March 18, 1983.

The Michigan Daily, April 16, 1983.

The Michigan Daily, September 5, 1985.

Washtenaw County Coalition Against Apartheid, Newsletter, Sept./Oct. 1985, Vertical File: Washtenaw County Coalition Against Apartheid, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

Janice Love, The U.S. Anti-Apartheid Movement: Local Activism in Global Politics (New York: Praeger Publishers, 1985)

University of Michigan Regents vs. Michigan, 166 Mich. App. 314 (1988) 419 N.W.2d 773, Accessed April 29, 2015, www.leagle.com/decision/1988480166MichApp314_1445.xml/UNIVERSITY%20OF%20MICHIGAN%20REGENTS%20v.%20MICHIGAN