Divestment as an Activist Strategy

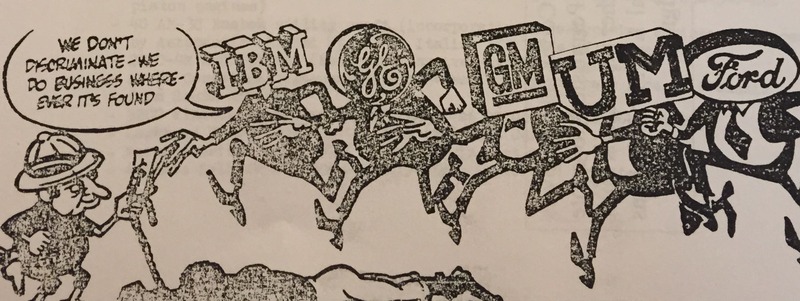

Divestment was a strategy chosen on a much larger level, chosen by the liberation movements and people of South Africa, not by us, to put pressure on the government, coordinated in the US by the Southern Africa committee in NY. It was part of a comprehensive strategy - military (we were not about to start killing anyone in Ann Arbor), sports boycott (also very effective) and economic and military boycotts. We worked to get universities, city and state governments to divest - and educate the American people and ourselves, about South Africa and what was going on, the links to the USA businesses involved in making money off the backs of impoverished people in SA and elsewhere. This was a one of many strategies and certainly effective for us, in the USA. - Ansell Horn in a 2015 interview

Economic actions were popular methods to pressure South Africa, even beyond college campuses. In 1986, under President Ronald Reagan, Congress passed the Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act of 1986. The Act imposed sanctions agains South Africa and listed preconditions for the repealing of the sanctions; the preconditions amounted to the end of apartheid policies. President Reagan vetoed the bill, claiming that Congress' measures would end up hurting the black population of South Africa. He offered to impose sanctions via executive order while working with Congress, but many around the nation and the world, including Bishop Desmond Tutu, condemned Reagan's veto. South African graduate student John Hendricks said that, "South Africa and Reagan are smitten with each other." Shortly after the veto, Congress overrode Reagan's veto. It was the first time in the twentieth century that Congress overrode a presidential veto on foreign policy. Furthermore, the defeat was made worse for President Reagan, since it was Congressional Republicans who spearheaded the override effort.

One of the anti-apartheid movement's biggest contributions to future activist movements was its popularization of divestment as an activist strategy. Following the anti-apartheid movement, student-activists continued to target university investments as a way to force change in the wider world. As a strategy, divestment proved to be less powerful as a financial tool than as a broadcasting tool. Usually, only a small fraction of a corporation's stock was owned by colleges and universites so divestment rarely had a significant impact on their bottom line. However, divestment campaigns often drew significant media coverage. In the anti-apartheid movement, widespread protests for divestment brought national and international attention to the cause, which was a crucial factor in the eventual end of the apartheid regime. Thus, divestment became a potent force in spurring national discourse about certain policies.

Since the end of the anti-apartheid movement, divestment campaigns have focused on a range of issues. Some college students have protested their universities' investments in corporations whose actions damage the environment. There have been calls for divestment from the coal and oil industries. For example, in February of 2015, students at Harvard University staged a sit-in at the office of the president, Drew Faust, to urge for institutional divestment from fossil fuels. Other divestment movements have focused on human rights or international politics. At the University of Michigan, divestment from Israel became another prominent issue and cause of protest and discussion on campus.

Sources for this page:

Franta, Benjamin, "Fossil Fuel Divestment: Reasons for Disruptive Forms of Protest Against the Harvard Corporation," Huffington Post, March 6, 2015, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/benjamin-franta/fossil-fuel-divestment-re_b_6812164.html.

Hendey, Eric, "Does Divestment Work?," Harvard University Institute of Politics, 2015, http://www.iop.harvard.edu/does-divestment-work.

Butterfield, Fox, "Harvard Cuts South Africa-Linked Holdings," New York Times, October 3, 1986.