The Sharpeville Massacre, 1960

Few events loom larger in the history of the apartheid regime than those of the afternoon of March 21, 1960, in Sharpeville, South Africa. Throughout the 1950s, South African blacks intensified their resistance against the oppressive apartheid system. Sharpeville, home to 26,000 blacks within the larger town of Vereeniging, located south of Johannesburg, seemed an unlikely setting for a watershed moment in the history of apartheid resistance. Before the massacre, white officials considered Sharpeville a small, insignificant, and even a “model” black township. Among other apartheid policies, Sharpeville blacks and their national compatriots were particularly outraged by laws requiring non-whites to carry government-issued passes, an effort by the apartheid regime to exert further control over the mobility of the black population. Mobilized in part by the Pan-Africanist Congress, one of the national organizations formed to resist apartheid, the demonstrators swelled around the police station starting in the early morning, and by the afternoon police recognized that the protest would not subside without proactive efforts by authorities.

Official figures counted 69 dead and about 50 wounded, though further analysis has raised the human toll to at least 200 wounded, “mowed down” by police who fired into a crowd of about 4,000 unarmed protesters. Available evidence seems to discount theories that the shooting that began was premeditated, but the scale and manner of the killing was horrific nonetheless. Physicians who treated the fallen reported that at least 70 percent of patients were shot in the back, and many of the victims were women and children. In the wake of the massacre, the government met widespread outrage among South African blacks with further clamp-downs on the resistance movement, and the conflict entered a new, even more polarized era.

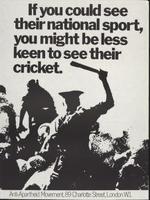

After the slayings perpetrated there, Sharpeville vaulted apartheid into international consciousness and galvanized protesters both within South Africa and abroad. Significantly, the international community could no longer ignore the encroachment of the apartheid regime on the freedoms of South Africa’s black population, sparking various anti-apartheid campaigns around the world. Boycott movements attempted to weaken the regime economically, a strategy that would become central to the divestment campaigns of the 1970s and 1980s. The International Olympic Committee banned South Africa from the Olympics, beginning in 1964, and similar bans prohibited segregated South African teams from participating in international rugby and cricket competitions. This 1960s-era poster demonstrates the vibrant anti-apartheid movement based in London and is one of the many international anti-apartheid images available in the Labadie Collection of social protest and radical political movements in Special Collections at the University of Michigan.

In the United States, the events in Sharpeville made South African policy a priority for a short period. Crucially, the 1960 massacre fomented a connection between the developing civil rights movement in the U.S and the plight of black South Africans. Previously, many mainstream civil rights leaders tended to regard the struggle against segregation in the U.S. and the anti-apartheid campaign as separate issues, uncomfortable with addressing the complexities of nationalist liberation movements in Africa. Pressure from U.S. and international organizations helped influence a shift in U.S. policy toward Africa, which became more sympathetic toward liberation movements under President John F. Kennedy, but stopped short of meaningful support. However, South Africa was soon overshadowed by domestic issues such as the nonviolent direct action phase of the civil rights movement and the resistance against the Vietnam War, delaying much further agitation in the U.S. until events in the mid-1970s brought apartheid back into the spotlight. This 1978 commemoration at the University of Michigan shows how the memory of the Sharpeville Massacre played a central role in the mass mobilization of the campus anti-apartheid movement nearly two decades later.

Sources for this page:

Philip Frankel, An Ordinary Atrocity: Sharpeville and its Massacre (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001)

Francis Njubi Nesbitt, Race for Sanctions: African Americans against Apartheid, 1946-1994 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2004)

The Globe and Mail, May 4, 1960

New York Times, March 22, 1960

The Chicago Defender, April 9, 1960

South Africa: Overcoming Apartheid, "Sharpeville Massacre," <http://overcomingapartheid.msu.edu/multimedia.php?id=65-259-E>

Have You Heard from Johannesburg? (PBS, 2010), directed by Connie Field

Interview of Ansell Horn by Mario Goetz, April 26, 2015