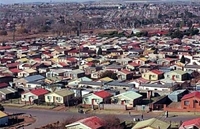

The Soweto Uprising, 1976

In 1974, South Africa passed the Afrikaans Medium Decree forcing all black schools to use Afrikaans and English as the languages of instruction. Afrikaans was used for mathematics, arithmetic, and social studies while English was used for general science and applied subjects. Indigenous languages were solely used for religion instruction, music, and physical education. At the time, most local governments recognized English and their indigenous language as the official languages due to the prominence of English in business and bypassed Afrikaans because of its association with apartheid. The South African government issues the decree after Afrikaans began to decline by invoking a clause of the 1909 Union of South Africa Act stating that only English and Dutch could be official languages. Since Afrikaans had replaced Dutch in 1925, the government policy made it the successor language to the clause. The policy had the effect of educating white students in their home language while forcing black students to learn in the dual language system.

Black South Africans widely criticized the decree because they viewed Afrikaans, as Desmond Tutu, Bishop of Johannesburg, put it, as the "language of the oppressor." Teaching organizations also objected to the decree, believing that the change in language of instruction would force students to understand the new language at the cost of the subject material and at the expense of critical thinking and expression. The controversy escalated on April 30, 1976, when students at the Orlando West Junior School in Soweto skipped school in protest. Black students from surrounding schools in Soweto joined the demonstrations against the decree and demanded educational treatment equal to that of the white South Africans. Teboho "Tsietsi" Mashinini, a student from Morris Isaacson High School, suggested a meeting take place on June 13, 1976, in which students from all around Soweto could come discuss what needed to be done to aid their campaign. Students at the meeting created an action committee they named the Soweto Students’ Representative Council (SSRC) and organized a mass rally for June 16.

On that day, some 10,000 to 20,000 black students walked from their schools to Orlando Stadium protesting the use of Afrikaans in black education. The SSRC as well as the Black Consciousness Movement and teachers in Soweto publicized the protest to students as they arrived at school, asking for a calm and controlled demonstration. Students from Morris Isaacson High School joined with students from Naledi High School to march toward Orlando Stadium but found that police had barricaded the route they had planned to take, and so they continued a different way. Carrying signs saying "Down with Afrikaans," "Viva Azania," and "If we must do Afrikaans, Vorster must do Zulu," the students reached the Orlando Stadiuml.

Missing paragraph: police shooting and stone throwing.

Hector Pieterson, a 13-year-old student, was the first casualty of the Soweto Uprising. Twenty-three other people would die on the first day of the uprising, including Dr. Melville Edelstien, who was stoned to death by a mob and left with a placard reading “Beware Afrikaners” around his neck. Violence spilled into the streets, specifically at outposts of the Afrikaner government, and the police patrolled the streets all night. One day later, 1,500 heavily armed police officers descended on Soweto, monitoring the area from helicopters and armored vehicles. The army was also ordered to stand by to show the military might of the Afrikaner government. While the government claimed that just 23 students were killed in the uprising, an estimated 176-700 people are believed to have died and more than a thousand injured over the course of the protest, which lasted well into the month of June.

Ripple Effects

In the aftermath of the Soweto Uprising, global anti-apartheid sentiment intensified as the image of Hector Pieterson’s body being carried reached news outlets. Some white South Africans joined in the outrage at the government’s treatment of the black students, with 300 white students from Johannesburg marching to protest the murder of children.

The Michigan Daily, the UM student newspaper, spread the story of the Soweto Uprising on campus starting with a June 17, 1976 article titled "Blacks riot in South Africa." The article addressed the critique that the apartheid government in South Africa used educational policies to keep the races divided, writing, "The question, however, runs deeper than language. Some South Africans see the opposition to Afrikaans as an expression of "black consciousness" or nationalist militancy. . . . Africans living around these [white urban] areas, like those in Soweto, have no political rights in South Africa but are regarded as citizens of tribal reserves which will eventually be granted political independence." The conclusion to the article pointed out that “unrest [in the black townships] is never far below the surface."

On June 19, 1976, the Michigan Daily published another articln by the Associated Press from Johannesburg, "Riots Climax in S. Africa." The article gave an update of the situation but also mentioned that the uprising "was the worst racial upheaval in South Africa, which has 18 million blacks and 4 million whites, since March 1960 when police in Sharpeville killed 69 blacks protesting laws requiring them to carry passes." A subsequent article on June 22, "More Rioting Erupts in South Africa," labeled the events the worst violence in the history of South Africa. The next day, on June 23, the Daily informed students that the "U.S. seeks peace in South Africa." Instead of focusing on the protests and rioting, the article highlighted the interest of the United States to "avoid 'a racial war' in southern Africa by promoting negotiations between white minority governments and black majorities." The article also quoted Secretary of State Henry Kissinger stating, "The United States feels South Africa has been too forceful in responding to black unrest."

As news coverage helped to spread awareness of the apartheid regime to campus, anti-apartheid groups shifted toward a new strategy of protesting university investments in corporations that supported the South African government and cited the violent suppression of the Soweto Uprising as a prime reason to divest.

Sources for this page:

Sifiso Mxolisi Ndlovu, "The Soweto Uprising" in The Road to Democracy in South Africa (Cape Town: Zebra Press, 2004).

"Soweto Student Uprising, <http://overcomingapartheid.msu.edu/sidebar.php?id=65-258-3>.

South African History Online, "The June 16 Soweto Youth Uprising," <http://www.sahistory.org.za/topic/june-16-soweto-youth-uprising>.