Campus Anti-Apartheid Movements before Soweto

Early Activism in the 1960s: SDS

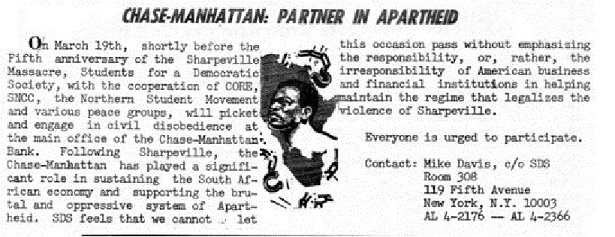

Although campus activism in the 1960s is usually associated with the civil rights movement and the Vietnam War, progressive activists sought to effect change on a wide range of issues, including South African apartheid. Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), a campus-based New Left movement based at the University of Michigan and one of the most prominent student activist groups of the 1960s, adopted apartheid as one of its main issues. Todd Gitlin, the group's president from 1963 to 1964, recalled that despite SDS's decision to launch national anti-Vietnam War protests in the mid-1960s, he was for a time more focused on anti-apartheid activism, which he considered "both morally compelling and intellectually interesting." On March 19, 1965, a few days before the fifth anniversary of the Sharpeville Massacre, Gitlin and other SDS activists coordinated a national protest against "the irresponsibility of American business and financial institutions" in "supporting the brutal and oppressive system of apartheid." Protesters picketed corporations in several cities, including banks in San Francisco and Boston and Chrysler’s Highland Park plant in Detroit. The largest of these protests involved 300 demonstrators in front of Chase Bank’s headquarters in Manhattan.

This February 1965 edition of SDS’s Bulletin newsletter outlines the organization's anti-apartheid protest strategy. SDS President Paul Potter wrote a letter to Chase (reprinted on page 16 of the Bulletin) demanding that the bank stop making loans to South Africa. In a response that would become familiar to anti-apartheid protesters throughout the movement, Chase claimed that it did not support the policies of the white South African government but also would not alter its business practices. Furthermore, Chase argued that “if one hopes for changes in the Republic of South Africa, or elsewhere, it would do little good to withdraw economic support.” In response, SDS decided to target “the ‘higher immorality’ of American corporations" and protest the bank. Also, early hints of a campus divestment program can be seen in the Bulletin. In a letter on page 11, Swarthmore student Walt Popper reported the discovery that his college holds stock in Chase and other companies doing business in South Africa. Although Popper's letter is primarily focused on action against corporations, New Left activists were beginning to make the connection between university investments and the apartheid regime.

Early Activism on Campus: African and African American Studies

The civil rights and black power movements on campus formed another powerful base for the early anti-apartheid movement at American universities, especially through the proliferation of African and African American Studies programs. Former University of Michigan professor Joel Samoff, who played a key role in the UM divestment campaign of the 1970s, discussed the emergence of the anti-apartheid movement on American campuses during a 2015 interview with our research team. For Samoff, his personal involvement in the anti-apartheid movement started with experiences in high school and accelerated during his graduate school work in African Studies at the University of Wisconsin in the late 1960s.

I first began hearing about it [apartheid] when I was in high school. That takes me back to the era of the confrontation in a place called Sharpeville which was in 1960. So the first anti-apartheid activity I remember participating in was a rally that was prompted by the events in Sharpeville. So it’s been an interest over a long period. It kind of faded a bit and it wasn’t until then became a graduate student that I was in a program in which I was working on Africa and rekindled that interest in South Africa.

As Samoff notes, the events in Sharpeville in 1960 spurred a wave of anti-apartheid protest worldwide, including in the U.S. Though this piqued his interest at an early age, he describes a decline in anti-apartheid activity as the 1960s progressed, similarly to the turn SDS made toward anti-Vietnam War protests and to the civil rights movement's focus on domestic issues.

However, this does not mean that anti-apartheid support disappeared. As a graduate student at the University of Wisconsin during the late 1960s, Samoff was immersed in a core group of African and Africanist scholars and activists, which solidified his commitment to African issues, including the fight against apartheid. At Wisconsin, and then after he joined the University of Michigan faculty in 1970 (and later, Stanford University), Samoff recalled how the anti-Vietnam War movement and the civil rights movement complemented each other on campus:

The activists in one were likely to be activists in the other. And I think that was certainly the case in the 1960s at Wisconsin and in many other places, including Michigan, and including Stanford... I think those all overlapped and intersected and I think many of the people who were activists had had some role in one or another of those. People were also involved in civil rights activities and the anti-war movement. But each of those efforts had its own dynamic and its own momentum, and there was, in this strong African Studies program at Wisconsin, a cluster of people, a core of people who were interested in South Africa...I wouldn’t say it [the Anti-Vietnam War movement] took attention away, they were overlapping. And so yes, it took attention away that on any given day you might have wanted to organize on South Africa that day, but in fact there was an anti-war rally. On the other hand, I think they were mutually reinforcing, so I don’t think it took attention away.

Thus, during the late 1960s and extending into the early 1970s, the anti-apartheid movement was perhaps overshadowed by the urgency of movements against the war and for civil rights, but the atmosphere of protest also helped sustain support for anti-apartheid action. In the years following the end of the Vietnam War, the connections and momentum that this period of intense activism generated, as well as international events, began to shift the focus of activists toward the anti-apartheid movement.

African Liberation and Black Consciousness on Campus

Students and faculty who were involved in the black nationalism and black power movements also often focused on the liberation struggles in Southern Africa and were especially important in the growth of the anti-apartheid movement on American campuses. At the University of Michigan in the early 1970s, the Black Action Movement (BAM) staged a series of protests and engaged in protacted negotiations with the university administration. The student-activists in BAM issued multiple demands, including increased minority student enrollment and increased support for African and African American Studies programs, as this 1970 manifesto reveals. At UM, BAM and other African and African-American student organizations were instrumental in raising consciousness about racial injustice and postcolonial movements, increasing the awareness of African liberation and apartheid on campus.

African students at the University of Michigan played leading roles in two campus groups that focused early attention on apartheid, the African Students' Association and the Southern Africa Liberation Committee (SALC). Josué Njock Libii, the president of the African Students' Association (ASA) at UM during the late 1970s, believed that students from Africa had a particular role to play in bringing consciousnesses about the apartheid regime to the broader UM community. In a 2015 interview, Libii explained that the ASA "wanted to provide leadership [for the anti-apartheid movement], because it was primarily an African burden." Speaking of the ASA, Libii stated that "we viewed ourselves as privileged people: we were university students attending one of the best universities in the world; in those days, almost all of us were on full scholarships, provided by our homes governments, by the governments of the USA, by NGOs, or by private organizations." According to Libii, the ASA worked closely with African Studies professors such as Joel Samoff and reached out to students involved in the Black Action Movement, antiwar activism, environmentalism, progressive religious groups, and other left-oriented causes. The ASA also viewed its mission as part of the Black Consciousness movement led by South Africans such as Stephen Bantu Biko, which encouraged black pride and advocated liberation.

Contributing to this growing activism on campuses was the global anti-apartheid network that had existed for decades. Organizations such as the ACOA provided resources for budding movements on campuses, including at the University of Michigan. In this flyer, a subsidiary of the ACOA, the Africa Defense and Aid Fund, sponsored free movies for the public to raise awareness and educate the campus community about southern Africa and apartheid.

African students and their allies founded the Southern African Liberation Committee (SALC) at UM in 1975, one year before the 1976 massacre in Soweto that turned anti-apartheid into a mass movement on American campuses. SALC co-founder Ansell Horn, a white native of South Africa and UM graduate student in political science, recalled that "black and white worked together" in the anti-apartheid movement at UM. In a 2015 interview, Horn stated that "we were supporting the liberation of all South Africans, . . . including whites. Many whites joined the movement and made sacrifices for this cause. . . . When one person is persecuted, . . . all are affected and complicit." SALC and the African Students' Association publicized the apartheid issue to UM students by distributing literature and bringing leaders from the African National Congress and other liberation groups to speak on campus. These groups organized many of the key protests during the second half of the 1970s, often in response to violent crackdowns by the South African government. This flyer advertising a mass meeting in 1976 called on UM students to support the liberation movements in South Africa, Namibia, and Zimbabwe as part of the "world-wide struggle against Imperialism." The flyer also condemned the University of Michigan for owning stock in corporations that did business with colonial regimes in Southern Africa, foreshadowing the divestment strategy that campus activists would soon embrace.

Michigan State University: A Center of Activism

At Michigan State University, professors and activists founded the Southern African Liberation Committee in 1973, two years before an identically named group arose at the University of Michigan. The SALC organization at MSU played a central role in promoting the broader anti-apartheid movement in the state of Michigan and helped pioneer the divestment strategy in campaigns directed at local and state governments as well as the MSU Regents. Based in East Lansing, the SALC group at MSU operated very close to the state capital, a geographic location that became pivotal to its influence. Campus minister Warren “Bud” Day co-founded SALC with graduate students and professors who had ties to MSU's African Studies Center and other activists who supported the African liberation movement. In the early days, SALC focused on raising awareness on campus through educational events and provided support for African liberation groups. Starting in 1976, SALC leaders began to target local institutions for divestment. Already affiliated with other national anti-apartheid organizations, SALC followed the model of targeting city councils as had been done in Washington, D.C. and Gary, Indiana. History suggested that that the East Lansing city council would be open to negotiation, because the anti-Vietnam War movement had lobbied successfully for a resolution in the past. In 1977, David Wiley and Marylee Crofts, both academics focused on Southern African issues, took leadership positions at the MSU Center for African Studies, and they proved to be pivotal to SALC’s success. On August 3, 1977, the East Lansing City Council unanimously adopted a resolution pledging to divest from corporations that did business in South Africa, a key turning point in the anti-apartheid movement in Michigan.

Academics affiliated with African Studies programs therefore played a key role in the origins and expansion of the campus anti-apartheid movement, as shown by the two SALC organizations at Michigan State University and the University of Michigan. When asked about how the anti-apartheid movement came to the state of Michigan in a 2015 interview, Heidi Gottfried, a founding member of the Washtenaw County Coalition Against Apartheid and a key Ann Arbor activist, identified the crucial role of professors and scholars in bringing issues to campus:

The reason why MSU, it was through David Wiley…He was a professor of African history. He knew Joel Samoff… He was absolutely central to these activities and so it was through those networks, these kind of left African historians, where we made connections to other universities. We were very much involved in trade unions in Detroit and other activists in the Detroit area.

In addition to these scholars, SALC and Michigan State University also benefited greatly from the presence of activists Frank and Patricia Beeman. Frank Beeman was the tennis coach and director of intramural sports at MSU. The Beemans had worked for civil rights in the 1960s, and Frank Beeman recalled that, "It just seemed to be a natural shift from civil rights to apartheid." Also, Patricia’s brother, Rick Houghton, was a missionary in Namibia, and he kept the Beemans informed on what was happening in Southern Africa. The Beemans relied primarily on moral arguments against apartheid and worked tirelessly to spread educational materials on South Africa and divestment. Frank Beeman recalled that they believed "people would do what was right if they knew the truth, if they knew what was actually happening." The history of anti-apartheid activism at Michigan State University shows that a dedicated group of professors and students was already fully engaged in the struggle against the South African regime before the high-profile repressions in Soweto and elsewhere in the late 1970s. But these shocking events, more than anything else, would catapult the issue of apartheid to the attention of the American public and lead to mass divestment protests designed to change university and government policies.

Sources for this page:

Todd Gitlin, The Sixties: Years of Hope Days of Rage (New York: Bantam Books, Inc., 1987), esp. p. 179.

The Wall Street Journal, March 22, 1965.

Interview of Joel Samoff by Aaron Szulczewski and Mario Goetz, May 7, 2015.

Interview of Josué Njock Libii by Mario Goetz, April 15, 2015.

Interview of Ansell Horn by Mario Goetz, April 26, 2015.

Interview of Heidi Gottfried by Emily Bodden and Aaron Szulczewski, April 9, 2015.

"Unit 5. Reigniting the Struggle - The 1970s through the Release of Nelson Mandela," South Africa: Overcoming Apartheid Building Democracy, Michigan State University, <http://overcomingapartheid.msu.edu/unit.php?id=65-24E-7>.

The South Africa Catalyst Project, Anti-Apartheid Organizing on Campus ... and Beyond (Palo Alto, Calif.: The South Africa Catalyst Project, 1978).

Janice Love, The U.S. Anti-Apartheid Movement: Local Activism in Global Politics (New York: Praeger, 1985).

Marc Fisher, "The Second Coming of Student Activism: Showdown over South Africa," Change (Feb. 1979), 26-30.

William Minter, Gail Hovey, and Charles Cobb Jr, eds., No Easy Victories: African Liberation and American Activists over a Half Century, 1950-2000 (Trenton, New Jersey: Africa World Press, 2007), <http://www.noeasyvictories.org>.

Interview of Frank Beeman at <http://www.noeasyvictories.org/interviews/int15_beeman.php>.

Additional information about campus organizations at the University of Michigan and Michigan State University can be found at the African Activist Archive, <http://africanactivist.msu.edu/index.php>.