In Their Own Words

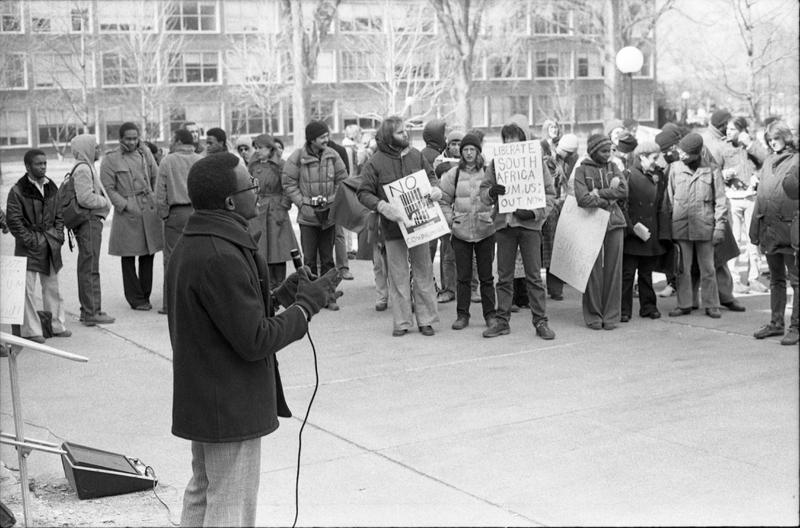

Here, we provide a space for anti-apartheid activists to present their own views on the broader successes and legacies of the movement on Michigan's campus, as well as the national movement as a whole.

For Heidi Gottfried, a founding member of the WCCAA, it was important to stress that South Africans ended apartheid, not college students in the U.S. However, she felt that she and her fellow activists played an important role in generating necessary international pressure, which was an important lesson in the ability of college students to make a difference in the world:

Were we successful in stopping apartheid? No, but we certainly put pressure. International pressure was really important for the ANC and the liberation movement internally- but it was their struggle that won and transformed their own society...the international pressure helped.

The histories we were responding to, we were also a part of... Those histories made a difference, the fact that we came to a college campus that was involved in these movements and was so important to why the University of Michigan was one of the leading universities in the struggle... Having these alternative histories is really important for the students to read, to know that they can be a part of making a difference at the University of Michigan.

For Ansell Horn, a founding member of the SALC at Michigan, the anti-apartheid movement was a defining and instructive chapter in the lives of those who chose to get involved. It inspired, and continues to inspire people to join the many, interconnected struggles for justice and equality:

The main legacy of the movement - we learned a hell of a lot by being involved and it affects our lives, work and viewpoints to this day. The fight for justice and equality is not over, not in SA, nor in the USA. Now we need to look at what is happening in the USA. Pick your issue, get involved, they are all connected. This is what we learned by being involved the the anti-apartheid movement.

For Matthew Countryman, a student leader during Yale's divestment campaign in the mid-1980s, the anti-apartheid movement was especially important because it served as a bridge between the radical movements of the 1960s and 70s, and ushered in a new era of multicultural protest that continues to inform movements today:

For Joel Samoff, a former UofM professor and long-time anti-apartheid activist and scholar, the successes and legacies of anti-apartheid activsim are manifold and complex:

On success at UofM and beyond:

Ultimately there was an effective divestment (at Michigan) in a way that didn’t happen at Wisconsin and didn’t happen in some other places. I think that had at least as much to do with state action as it did with University of Michigan action… In that respect there was greater success.

I speak now as somebody who wrote maybe one hundred different op-ed pieces at some moment or other about what divestment was all about. Starting out, actually, I was very skeptical about that strategy. I had to be persuaded. It turned out to be a good idea- I was wrong. The issue was to put pressure on South Africa, not to put pressure on Ford or General Motors, or the University of Michigan. The goal, in the end, was apartheid. The focus was not U.S. institutions, but the events that were happening in South Africa. I think there is no doubt that the external pressure played some role. It didn’t end apartheid. Apartheid was ended by South Africans, who were activists in their own country. But that external support, I think, was significant.

The divestment movement, then, provided a mechanism for doing a couple of things. One was to put the pressure on institutions, like the University, but not just the University, other institutions as well. It also was a mechanism that enabled people with different sorts of levels of political engagement to come together. So in the divestment movement, or the anti-apartheid support movement, there was room for people who wanted to support the guerrilla struggle, and who would have been perfectly happy to raise money and buy weapons and send them to guerrillas in South Africa. But there was also a space for, say, a church group, that was prepared to collect blankets and clothing for refugees in a refugee camp in Botswana across the border. They could all come together under that umbrella.

Now, was it successful in getting divestment? Not immediately, but I didn’t think then, and I don’t think now that that’s the full measure of success. The goal was apartheid in South Africa. One lever to try to work on that was to get U.S. companies to disinvest. One way to try to get U.S. companies to disinvest was to get holders of their stock to divest. But in the course of the divestment part of it, it became a rallying motif- a rallying theme- that was effective in very different settings.

On the legacies of the anti-apartheid movement:

You’re really asking two questions: “Why was it important for universities, particularly the University of Michigan?” which is one question, and a somewhat different question is about U.S. politics. The U.S. politics part of it was I think it effectively moved the center of gravity of what was the Democratic Party, but also anybody who wanted to claim to be a liberal. Now it’s not such popular term, but in that era, certainly in the 60s and 70s, people wanted to situate themselves as progressives on one issue or another, and the anti-apartheid movement effectively moved the center of gravity. It pushed people to say “you cannot have respectable credentials as a progressive if you’re not outspoken on several issues, support of anti-apartheid being one of them.”… If you work your way back through the history the period of the late 60s was also the period of the assassination of Martin Luther King and of Robert Kennedy and of urban riots, and so there were uprisings- there was stuff going on that people could not simply ignore.

The anti-apartheid movement was a participant in that and it had an internationalizing role, and it had an internationalizing role that was a sequel, in some ways, to the anti-Vietnam War movement. It excited attention; it excited interest. As I said, nobody can really stand up and defend slavery. Nobody can stand up and defend institutionalized racial discrimination, and so it really angered people- it really incensed people, saying, “in this modern era how can it be that…,” in the same way that some people get really incensed about laws that differentiate between the status of women and men, laws that differentiated between the status of white and black people. Today, there are countries that will stand up and defend differentiation between women and men, but nobody will stand up and defend differentiation on the basis of race: literally nobody except South Africa. So in that respect, it really put into sharp vision a major injustice, and it kind of put it in front of people. It was a mechanism by which people came together, but it also had an international dimension.

It was an international dimension that was playing itself out through the period of the decolonization of Africa. The beginnings of the decolonization of Africa was the end of the 1950s, but the major period of the decolonization was the 1960s. So the anti-apartheid initial, basic organizing coincided with that, and kept that as a wide phenomenon. It also, in a way that other issues were not as effective in doing, permitted saying to the faculty and to academic institutions, “Where do you stand on the big issues of the world? You can’t just sit back and say ‘We’re an academic institution and we have multiple sides and multiple voices.’” Yes, that is the role of an academic institution, but there are some issues on which neutrality is not acceptable, we argued, and racism is one of them, and here is institutionalized racism, so no, you can’t step back and say “we’ll have a debate and both sides can say what they want.” There aren’t two sides to racism, we argued. I think the anti-apartheid effort did that. The anti-apartheid effort was also a clumsy, awkward, spasmodic, hit-and-miss way for student activists, trade unionists, church activists, academics who were not students, that is, academics who were farther along in their professional careers, to come together and say “We have common ground on things, and we will work together, stand together, and pursue that.” That was the case for the civil rights movement in the U.S., it was the case, in part, for the anti-Vietnam War organizing, but I’m not sure there has been anything since the anti-apartheid movement that has been able to do that.