Jim Crow in the Big House

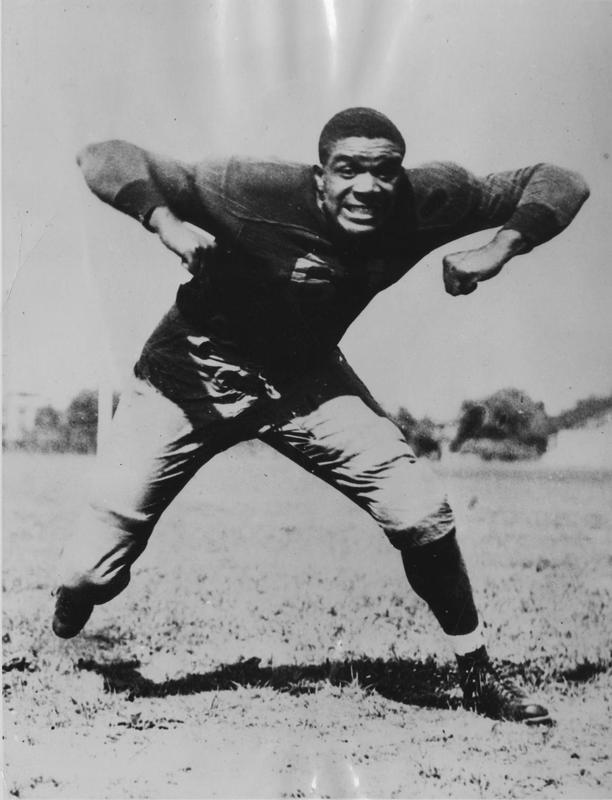

African American athlete Willis Ward attended the University of Michigan from 1931 to 1935. As a freshman, Ward won the NCAA high jump championship.[1] He also outran would-be Olympic gold medalist Jesse Owens in the sixty-yard dash in 1934, the only man to have beaten Owens in a sprint event.[2] Though he was recognized as one of the greatest track athletes in University history, controversy arose when he tried out for the football team.

While African-Americans were celebrated on the track team, the idea of black players on the football team elicited opposition. There had not been an African American Michigan football player since George Jewett played for U-M in 1890.[3] The exclusion of black athletes from the football team emanated primarily from football coach and Athletic Director Fielding Yost. Yost, the son of a Confederate soldier, effectively prohibited black athletes from playing on his team when he became football coach in 1901.[4] As athletic director, Yost permitted African -Americans to compete in other sports, primarily as a response to the success of black athletes at other universities. When it came to football, however, Yost maintained the sport as “a simple, Anglo-Saxon desire for clear energetic sport.”[5]

When Coach Harry Kipke put Ward on the team in 1932, Yost and Kipke reportedly came to blows.[6] Kipke stood by his athlete, and Ward played four games during the 1932 championship season. The next season, Ward played in all eight games and contributed to the Wolverine’s second consecutive national championship.

Ward’s place on the football team became more controversial during the 1934 season, when Yost scheduled a game against Georgia Tech. When competing at southern universities, northern schools often acquiesced to the norms of Southern racial segregation by excluding black players from the game.[7] Increasingly in the 1930s, northern schools also excluded black players even when playing on their own home fields.[8]

Yost was aware that Georgia Tech would demand the exclusion of Ward when he scheduled the game at the Big House in November 1934. He assured Georgia Tech Coach William Alexander that Ward would be benched, after Alexander notified Yost that it “[would] be impossible for Georgia Tech to play the game unless some arrangement can be made to leave Ward, or other negro players, on the sideline that day.”[9] Aware of the controversy the benching of Ward could create, Alexander offered to cancel the game, but Yost was determined to host the match.[10]

Coach Kipke informed Ward of his benching in the summer of 1934.[11] Ward determined he would quit the team, but Kipke coerced him to stay, telling Ward that he would never allow another black player on the team if he walked out.[12] Ward, concerned for the future of black athletes at Michigan, decided to remain on the team in the face of racial discrimination.

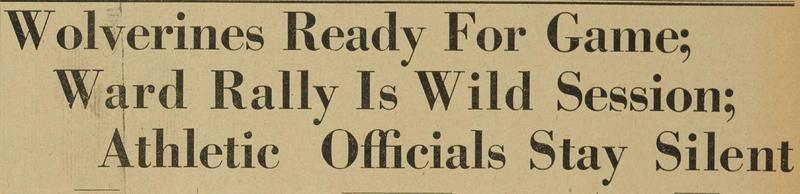

When news broke about Ward’s benching, it became a national story. Letters streamed into the Athletic Department from alumni, pressuring the University to address the Ward situation. Protests led by the National Student League occurred on campus; “LET WILLIS WARD PLAY OR CANCEL THE GAME,” was their slogan.[13] Ward himself came under criticism from the black press and was called a coward and an “Uncle Tom” for not quitting the team.[14]

The U-M administration recused itself from any responsibility in the matter. Ralph Aigler, a member of the Board in Control of Intercollegiate Athletics, asserted that participation in intercollegiate athletics was not a matter of right or duty, but of privilege.[15] University President Alexander Ruthven refused to answer any letters concerning Ward.[16] The university placed all discretion in the hands of Athletic Director Fielding Yost.

Yost did not issue a public statement regarding Ward’s benching, but he secretly conspired to remove protesters. In the days leading up to the game, Yost dispatched a number of students to a rally in support of Ward in an attempt to spoil a sitdown protest at the game.[17] Yost also hired Pinkerton detectives to spy on the leaders of the protests, in order to foil any other plan they had to protest the game.[18]

When the day of the game came on October 20, 1934, not only was Ward barred from the field, but Yost also prohibited him from entering the stadium, and Ward spent the day at his fraternity house.[19] This experience left a deep impact on Ward, and altered the trajectory of his athletic career. “The thing soured me on athletics,” Ward said, “It told me it just wasn’t worth it.”[20] Ward, who many anticipated would win several gold medals at the 1936 Berlin Olympics, gave up sports, saying he did not want to be Jim Crowed again—this time by Adolf Hitler.[21]

After Ward, it would be seven years before another black athlete played on the Michigan football team—after Yost had retired in 1940. Ward went on to become a distinguished lawyer and judge, influenced by his experiences, with the desire to help people.[22] Ward was inducted into the University of Michigan Athletic Hall of Honor in 1981.

[1] Associated Press, “National Collegiate Stars to Enter Olympic Trials: 15 Help Make New Records,” Ironwood Daily Globe, June 13, 1932.

[2] Steward, Tyran Kai, “Jim Crow in the Big House: The Benching of Willis Ward and the Rise of Segregation in the North.” PhD diss, Eastern Michigan University, 2009, 127.

[3] Ibid., p. 66.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid., p. 147.

[6] Ibid., p. 66.

[7] Ibid., p. 66.

[8] Ibid., p. 85.

[9] Ibid., p. 86.

[10] Ibid., p. 144.

[11] Ibid., p. 105.

[12] Ibid., p. 106.

[13] Ibid., p. 169.

[14] Ibid., p. 108.

[15] Ibid., p. 157.

[16] Ibid., p. 158.

[17] Ibid., p. 204.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Ibid., p. 127.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Black and Blue: The Story of Gerald Ford, Willis Ward, and the 1934 Michigan-Georgia Tech Football Game, Stunt 3 Multimedia, 2011.