The Aigler Years

In 1910, the U-M Board of Regents decided that control of athletics should be vested in a board of eleven faculty, who formed the Board in Control of Intercollegiate Athletics. The Board administered athletic budgets, managed Michigan sports revenues, and made policy decisions pertaining to athletics.[1] The Board also oversaw the Department of Physical Education when it was established in 1920, delegating its funding and nominating its members.

The Board’s first records indicated the tremendous financial success of Michigan football. The 1910 report shows that football generated over $25,000 in revenue. All other sports, however, ran at a deficit. The only year that football operated at a loss was its 1918-1919 season, which the Board attributed to WWI and the influenza epidemic.

In 1913, Ralph Aigler, a U-M law professor, was named chairman of the Board in Control of Intercollegiate Athletics, a position he would retain until 1941. He remained a member of the Board until 1955. After becoming chairman, Aigler was key in getting U-M to rejoin the Western Conference in 1917, known today as the Big Ten Conference.[2] People first started to refer to the conference as the Big Ten after U-M rejoined.[3]

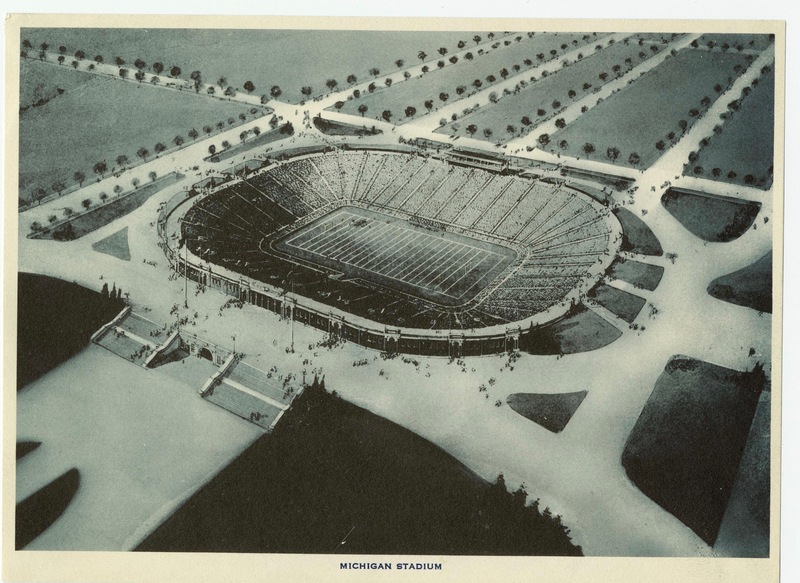

The 1920s were a period of enormous growth for Michigan athletics. By the middle of the decade, football grossed over $420,000 annually, while all other sports continued to run at a deficit. The growth of the football program allowed U-M to build a new football stadium. Michigan was able to secure loans at a very low interest rate by issuing bonds that gave bondholders prime seats at football games. In 1927, the University built Michigan Stadium, and its seating capacity drove profits up even further. In 1927-28, the football program grossed $773,000 in ticket sales, and the Athletic Department grossed over $1 million that year.

With more money came more controversy. As profits in football increased nationwide, universities were criticized for being “commercialized” and focused solely on profits at the expense of students. In 1929, a report by the Carnegie Foundation accused many colleges of this, including U-M. Even some within the University made this charge, including the U-M president. In 1928, U-M President C.C. Little declared, “University presidents who honestly believe in physical training for all students discover that agents other than the students themselves have taken hold of much of the athletic program and have shaped it to fit the recreational needs of the general public and the press.”[4] While the Board acknowledged that huge sums of cash flowed through its hands, they said that football was not played to make a profit. Football profits, according to the Board, were merely incidental, “the game would be the same if the stands were empty or open only to students. One cannot get much aroused over the fact that we take large sums of money from people under such circumstances.”[5] The Board believed that the profits were benefiting students as they were partly used to build athletic facilities for students.

When the Great Depression began in 1929, Michigan athletics revenues fell dramatically. Football went from earning over $880,000 in ticket sales in 1929-1930, to earning $227,000 in 1931-32. The program still managed to turn a profit, but it was the only sport to do so, and the Athletic Department struggled to maintain their other programs during the 1930s.

To make matters worse, the 1932 federal Revenue Act excised a 10% tax on a variety of admissions including collegiate sporting events.[6] Ralph Aigler, along with other officials from the NCAA, was determined to fight the new federal law. In 1933, the NCAA formed a committee to pursue the elimination of this new tax, and named Aigler as the chair.[7] Michigan had begun refusing to collect the admissions tax in 1935, choosing to wait for a decision from the United States Supreme Court on the legality of taxing college sporting events. In 1938, the Supreme Court ruled that the tax was constitutional in Allen v. Regents, and the University began to comply with the law, having failed to end the new tax.[8]

[1] 1923-1924 Annual Report p. 1-2, Annual Reports 1911/1912 – 1924/25, Box 32, Board in Control of Intercollegiate Athletics (University of Michigan) records, University of Michigan Bentley Historical Library, Ann Arbor, MI.

[2] Michigan Alumnus Quarterly Review, December 7, 1957, Writings, Athletics, Box 15, Ralph W. Aigler Papers, University of Michigan Bentley Historical Library, Ann Arbor, MI.

[3] Wikipedia contributors, "Big Ten Conference," Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Big_Ten_Conference&oldid=785515804 (accessed

June 22, 2017).

[4] History of its establishment circa 1928 p.22, Box 2, John Sundwall Papers: 1921-1944, University of Michigan Bentley Historical Library, Ann Arbor, MI.

[5] 1929/30 Annual Report, Annual Reports 1931/32-1939/40, Box 32, Board in Control of Intercollegiate Athletics (University of Michigan) records, p.15, University of Michigan Bentley Historical Library, Ann Arbor, MI.

[6] 1931/32 Annual Report p.7 , Annual Reports 1931/32-1939/40, Box 32, Board in Control of Intercollegiate Athletics (University of Michigan) records, University of Michigan Bentley Historical Library, Ann Arbor, MI.

[7] 1934/35 Annual Report, Annual Reports 1931/32-1939/40, Box 32, Board in Control of Intercollegiate Athletics (University of Michigan) records, University of Michigan Bentley Historical Library, Ann Arbor, MI.

[8] 1937/38 Annual Report, Annual Reports 1931/32-1939/40, Box 32, Board in Control of Intercollegiate Athletics (University of Michigan) records, University of Michigan Bentley Historical Library, Ann Arbor, MI.