Title IX Resources

Background

In the late 1960s, women’s’ sports were organizationally merged with men’s, but that did not bring robust funding or opportunities equal to men’s. In fact, when the Women’s Athletic Association (WAA) dissolved and the men’s and women’s physical education programs merged, the remaining women’s club teams found themselves isolated in terms of funding. In April 1970, men’s and women’s sports clubs united under the Michigan Sports Club Federation (MSCF) , which was allotted $10,000 for start-up funds. The sports clubs received minimal funding from the Athletic Department, and fundraising and player dues covered the remainder.[1]

When Title IX passed in 1972, many athletic directors opposed it on the grounds of funding, fearing that existing men’s programs would lose resources. Although Title IX implementation at U-M was slow due to Athletic Director Don Canham’s opposition, funding for women’s sports did increase exponentially throughout the 1970s and 1980s.

Funding

When six varsity sports were first offered to women in the 1974-75 academic year, the total operating budget of the program was about $125,000. In the next few years, increases in funding allowed for the purchasing of new equipment, hiring of staff, and building and renovating of some locker rooms and training facilities. By the 1978-1979 academic year, the budget had quadrupled to $603,000.[2] Although this was a significant improvement from previous years, extreme inequities between the men’s and women’s athletic programs persisted. Decades later, varsity tennis player Marissa Pollick explained in The Michigan Daily that no new locker rooms were initially built for female athletes. They had to use "the back bathrooms of the building,” she recalled, “and I can literally still smell it.”[3]

Title IX promised equality, but it took decades to achieve.

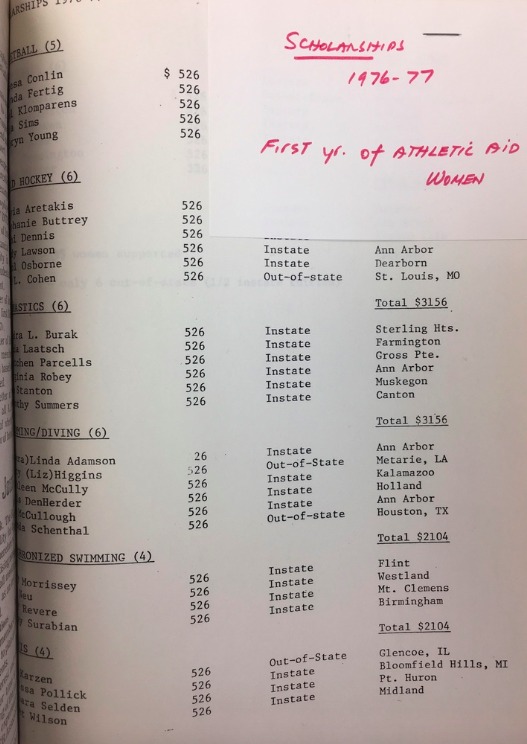

Scholarships

One of the largest discrepancies between the men’s and women’s programs was in scholarships. Under Title IX, institutions had to offer opportunities for scholarships to men and women that were proportional to the number of competitors in each program.[4] Scholarships for college athletes had long raised concerns about professionalism, and the women’s athletics program had been devoted to a principle of amateurism. As a result, some administrators, even Associate Director of Athletics for Women Marie Hartwig, feared the consequences of scholarships for female athletes. When Hartwig retired and Virginia Hunt took over the position in 1976, 38 half-tuition scholarships were made available to women.[5] One varsity women’s tennis player remembers that during that season, four out of ten players could earn scholarships, so they had to play each other to earn their scholarship.[6] The scholarship fund for women’s athletics continued to gradually grow in the following years, and the “women’s programs became comprehensive and exceptional” when the Big Ten Conference admitted women’s teams in 1981.[7]

[1] Sheryl Szady, “The History of Intercollegiate Athletics for Women of the University of Michigan” (PhD diss., University of Michigan, 1987).

[2] Chronology of Implementation, Title IX Chronology of Implementation 1979, Box 6, Women's Athletics Records, University of Michigan Bentley Historical Library, Ann Arbor, MI.

[3] Alexa Dettelbach, “Marissa Pollick: Michigan’s Unsung Title IX Hero,” The Michigan Daily, February 27, 2014, page 7A.

[4] Summary Report on Final Regulations Implementing Title IX of the Higher Education Amendments of 1972, Title IX Correspondence, Reports 1975, Box 6, Women's Athletics Records, University of Michigan Bentley Historical Library, Ann Arbor, MI.

[5] David Diles, “The History of Title IX at the University of Michigan Department of Athletics” (PhD diss., University of Michigan, 1988).

[6] Alexa Dettelbach, “Marissa Pollick: Michigan’s Unsung Title IX Hero,” The Michigan Daily, February 27, 2014, page 7A.

[7] David Diles, “The History of Title IX at the University of Michigan Department of Athletics” (PhD diss., University of Michigan, 1988), page 207.