Michigan Environmental Protection Act

In 1968, a group of citizens concerned with environmental issues founded the West Michigan Environmental Action Council (WMEAC) in Grand Rapids. From their earliest days, the group came face-to-face with the reality that conservation organizations, which were “usually volunteer, relatively poor, tax-deductible organizations,” could not “combat or contradict the constant public relations and scientific balderdash” of industries that claimed to act in the public interest.

In 1969, the WMEAC--under the leadership of activist Joan Wolfe--sent a letter to Dr. Joseph L. Sax, an esteemed U-M Law professor and conservationist, requesting that he write a revolutionary environmental bill for the state of Michigan, writing, "...you are singularly qualified, as both a conservation and constitutional authority on law, to oversee such a project. (Some of us heard you at the EDF case in Grand Rapids and have also read your recent Saturday Review article, and are impressed).” As Wolfe referenced, Sax worked on a groundbreaking DDT (an environmentally harmful pesticide) case in Grand Rapids, Environmental Defense Fund vs. Michigan Department of Agriculture, in 1967. That hearing marked the first time the court heard testimony rather than just working with written briefs in such a case. Further, it was the furthest any pesticide suit against a government agency had gone thus far. The WMEAC asked that Sax research legal precedents and write a new bill to address the frustrations of thousands of environmental activists across the country about "the disregard for the public interest by some single-minded agencies, industries, and individuals." Although Wolfe later accredited Sax for the bill "entirely," Wolfe did propose the WMEAC's three provisional wishes, which would shape the future of environmental litigation at the state and federal levels:

1 - that if it incorporates a committee approach to environmental problems, that that committee not be merely advisory unless further protection is built into the law. (mention was made of the right to sue)

2 - that the makeup of any environmental committee overwhelmingly represent the best scientific-ecological-etc. knowledge

3 - that vested interests not be included in such a way that they would interfere with an excellent decision-making process

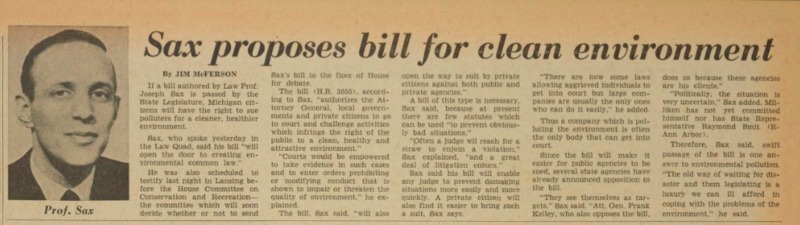

One week later, Sax agreed to research and write the bill, and Wolfe promptly made the necessary arrangements to have the bill introduced in April in the Michigan House of Representatives by Representative Thomas Anderson, the conservation committee chair. Before going to Washington D.C. to research for a year, Sax met with Anderson and his committee to delineate his plan for the groundbreaking House Bill 3055, the Michigan Environmental Protection Act (MEPA). This series of events sparked this revolutionary bill, which would allow citizens to sue corporations for harming the environment and thus “add a weapon to the arsenal of the public interest.”

The basis for this "weapon" was the public trust doctrine, which had its roots in an ancient Roman doctrine that protected the interest of the public in navigation and fisheries. Adapting that "traditional" law to combat "contemporary problems," Sax pivoted MEPA on that provision. In the video "The Environmental Lawyer," Sax explains the necessity of recognizing the "public has a right to a decent environment." "You must not only recognize the right," he declares, "but you must recognize that the right is enforceable by the public." This Michigan statute later redefined the role of citizens in protecting the environment inside and outside of the courtroom by allowing citizens to file lawsuits to enforce government regulations limiting pollution and economic development and therefore serve as watchdogs on corporations and government agencies.

In the nine months between April 1969 and January 1970, Wolfe and the WMEAC wholly devoted themselves to the cause. Although the WMEAC had a miniscule budget, no paid employees, and no office, they printed and disseminated thousands of Sax’s 13-page explanation of the bill to other environmental groups, interested individuals, and newspapers across the state. Wolfe also travelled around the state, speaking to any group that would listen and garnering a deep base of support. In December 1969, the WMEAC received its first signal that their thorough campaigning had paid off--a state legislative hearing on the bill set for January 21, 1970. Again, the WMEAC sent out thousands of SOS newsletters, asking that organizations either attend the hearing or let the WMEAC speak on their behalf. Students across the state played an important role in reprinting and distributing these newsletters.

Meanwhile, the opposition grew steadily as well although much of this occurred behind closed doors in those early months. One notable exception was the State Chamber of Commerce, publishing its own critique of the bill arguing that the citizen lawsuit provision “would create a serious threat to the operation and growth of business and industry...a complete bar to the current method of voluntary and workable cooperation between industry and government.” In a memo to Wolfe, Anderson described that “blast” from the State Chamber of Commerce as an example of “the kind of opposition...we are trying to smoke out in the hearings.” Concerns about the disruption of the relationship between government and industry and about the potential for citizens to overuse and thus abuse the citizen lawsuit provision formed the basis of the opposing viewpoints.

“We ought not to forget how useful it can be--indeed how essential--to ventilate important issues of policy outside the often confining traditional channels of the bureaucracy; particularly is this so when a bill like H.B. 3055 is under attack on the ground that it might shake up the well established formal channels of government a little bit. It might--and it should.” -Joseph L. Sax

Because of the radical nature of the citizen lawsuit provision, the opposing agencies and even many supporters of the bill, including Anderson and Wolfe, did not believe it could pass in both the House and the Senate without serious damages to its central provisions. However, they grounded themselves in faith that mass public support for the bill would prove the necessity of its passage.

“We were told from the beginning that it would be impossible to get this bill through. I guess because we were naive we went ahead anyway. I never really knew or thought we could get it passed. I was just determined to do everything to try. People kept saying, ‘You can get it through the House but not the Senate.’ Or they said, ‘You can get it through the House but it’ll be changed and it’ll really get messed up in the Senate.’ My reply was, ‘We’re not going to worry about that now. We’ll take one step at a time and fight to the end.’” - Joan Wolfe

On the day of the hearing, hundreds of concerned citizens attended, representing the majority of conservation and environmental organizations as well as a variety of other groups, including the Michigan PTA, unions, such as the UAW and the AFL-CIO, Save Our Air from the Upper Peninsula, and U-M’s Department of Zoology and the Regional Planners. Wolfe testified for WMEAC and 27 other organizations, including the Black Unity Council, the Grand Rapids and Kent County PTAs, and other local organizations. In her succinct yet potent testimony, Wolfe outlined the goals of the bill, addressed the opposing viewpoints head-on, and proclaimed the necessity of the citizen lawsuit provision to ensure the enforcement of regulatory statutes on industry and thus to preserve the state’s natural resources.This hearing proved that a wide variety of citizen groups firmly believed in the power of this bill, and this outpouring of support prompted many other groups to join in. Further, this hearing put academics, including Professor Sax and his law students, environmental activists, ecological experts, and others in conversation together about the significance of such a bill.

"Everybody in this room knows - unless he has hypnotized himself - that we are not moving fast enough. Most of us are unpaid volunteers who are naive politically...But we are now convinced that both the quality of life, and life itself, is endangered; that our children are being denied life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness, and we will no longer stand for words and public relations in place of deeds." - Joan Wolfe

Between January and June 1970, a series of hearings followed, often operating on just a few days notice, and citizens continued to showcase their support. In Grand Rapids, despite one of the worst snowstorms of the year, 450 people attended one such hearing in late February. As the locations of the hearings traversed the state to Detroit, Wolfe and her growing network of supporters continued to work tirelessly to ensure active citizen participation at these hearings by sending out newsletters and making calls to established organizations in the region. With each successive hearing more organizations and individuals got involved, and there was eventually hundreds of organizations working towards a unified goal: the passage of MEPA without weakening amendments.

In April 1970, the bill passed with an overwhelming majority (only three opposing votes) in the House without any of the suggested weakening amendments. The next obstacle was to pass the bill through the Senate, an event which even the bill’s main supporters deemed unlikely. Citizens remained devoted to the cause, as evidenced by the May 12th hearing which most people heard of only the day before. Wolfe, Sax, and many others closely examined each suggested amendment that threatened to weaken the bill, such as the one word change from “and” to “or,” which would have “taken all the teeth out of the bill, but the citizens got on the telephone, and wired and got to Lansing overnight on that little change.”

For several weeks, rumors about the state of the bill abounded, but on June 26th, 1970, the bill passed with a few amendments, which actually strengthened the bill. The strengthened bill returned to the House where it passed once again before arriving on the desk of Governor Milliken. On July 27th, the governor signed the act, and citizens around the state celebrated their tremendous victory for which thousands of individuals had fought. Ultimately, the passage of MEPA led to many controversial lawsuits, such as the WMEAC v. Natural Resources Commission and Tanton v. Department of Natural Resources, and sparked debates about the National Environmental Policy Act and many other bills in Michigan and in other states.

Sources

Joan Wolfe Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

West Michigan Environmental Action Council Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

Joseph L. Sax Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

David Chudwin Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

University of Michigan Television Center, “The Environmental Lawyer,” 1970, Box 8, Media Resources Center (University of Michigan) Films and Videotapes, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

Joan Wolfe, “A History of the Michigan Environmental Protection Act of 1970,” n.d. [early 1970s], https://dspace.nmc.edu/bitstream/handle/11045/10580/wolfe-history-of-mepa.pdf?sequence=6

Michigan Daily Digital Archives

"Action Line," Detroit Free Press, March 5, 1970, 1

“Courts called a needed weapon in battle to save environment,” The North Woods Call, January 28, 1970, 6

Joan Wolfe Statement, "Environmental Citizen Action," Hearings before the Subcommittee on Fisheries and Wildlife Conservation, Committee on Merchant Marine and Fisheries, U.S. House of Representatives, May 7, 1971 (Washington: GPO, 1971), 281-287

Interview of Sally Churchill by Hannah Thoms and Meghan Clark, December 11, 2017, Ann Arbor, Michigan