I. Origins of the Environmental Movement

The grassroots mobilization for environmental protection that led to the first Earth Day in 1970 built on nearly a century of efforts to address the contamination of water, air, and land caused by industrialization and urbanization. During the Progressive Era in the early 20th century, reformers warned that unregulated economic development was destroying natural resources and raised alarms about the public health crisis of crowded cities, where raw sewage and industrial run-off filled the waterways and smokestack pollution clouded the air that people breathed. Scientific experts, urban reformers, and women's groups promoted policies to reduce disease and clean up the air, land, and water. Conservation groups also began mobilizing in the late 1800s to protect wilderness areas and wildlife and regulate logging, mining, dam construction, and other assaults on natural resources. Early environmental activists such as John Muir, who founded the Sierra Club in 1892, were not so much radicals as deeply conservative visionaries who feared the encroachment of modernization and industrial expansion on America’s natural beauty, especially in the West.

Early conservationists urged the government to create national parks to preserve America's most beautiful wilderness areas and better regulate the development of natural resources rather than exploit them at an unsustainable rate. Creating national parks became a means of preserving these lands to maintain their ecological biodiversity as well as provide wilderness resources for hikers and other recreational enthusiasts. As the environmental philosophy spread, so did the concept of "ecology," an awareness of not only how the natural environment affects human life but also how the activities of humans negatively shape the environment. The environmental movement condemned the idea of competition between humans and nature, and the exploitation of natural resources, that they blamed on the values of industrial capitalism. The ecological sensibility idealized a state of natural coexistence, of mutual interaction, between humans and their environment.

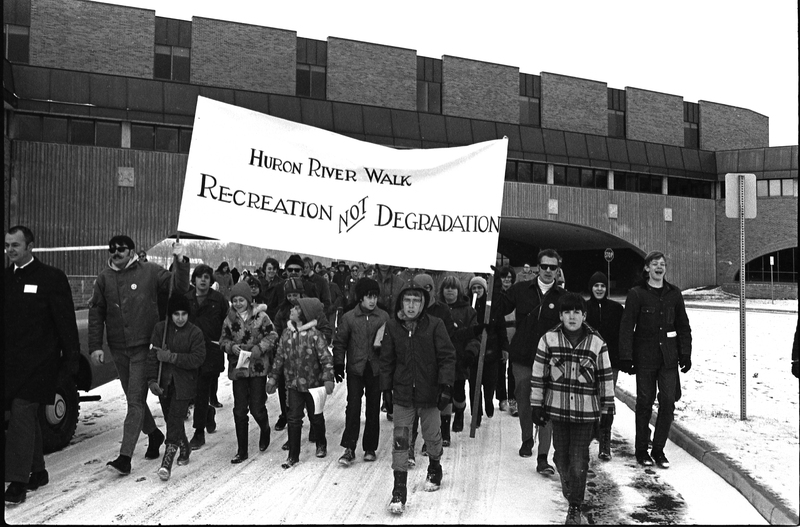

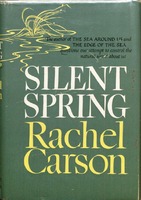

Many factors converged to accelerate environmental activism and increase ecological consciousness during the 1950s and 1960s. The unprecedented affluence of postwar America allowed millions of white middle-class families to move to the suburbs in search of bucolic landscapes and seek a quality of life that their same modern consumer society threatened through pesticides, smog, water pollution, and other hazards. Rachel Carson's book Silent Spring (1962) shocked middle-class readers with its expose of the harms caused by DDT and other chemical contaminants to animal life and human safety. Increasing numbers of women in Michigan and across the United States became active environmentalists to protect the safety of their children and the sanctity of their homes and neighborhoods from environmental threats. Established organizations such as the League of Women Voters raised public awareness about environmental issues, especially water pollution. The majority of these women activists, however, banded together to form local groups around specific issues such as the hazards of industrial pesticides, radioactive fallout from nuclear testing, and over-development of open spaces.

Air and water pollution disproportionately affected working-class, poor, and nonwhite communities in urban and rural areas alike, a pattern that ultimately merged civil rights, labor rights, and environmental consciousness into the environmental justice movement. Although they often have received less attention, African American activists also participated in early environmental campaigns, such as protests about lead poisoning in inner-city neighborhoods which, with the assistance of leading ecologist Barry Commoner, ultimately led to local government action in St. Louis. Mexican American and migrant farmworkers in California also protested against exposure to agricultural pesticides as part of the United Farm Workers movement, and industrial labor unions such as the United Automobile Workers (UAW) played a crucial role in promoting environmental protection that history has largely forgotten. The environmental movement, therefore, began with grassroots efforts from concerned citizens across the country and transformed into a national movement that combined wilderness protection with environmental justice, with many different types of activist pioneers demanding action from the government and polluting corporations. Though environmental awareness and activism, historically marginalized groups such as women, African Americans, Mexican Americans, and working-class union members also participated in the groundswell for change during the 1960s and 1970s.

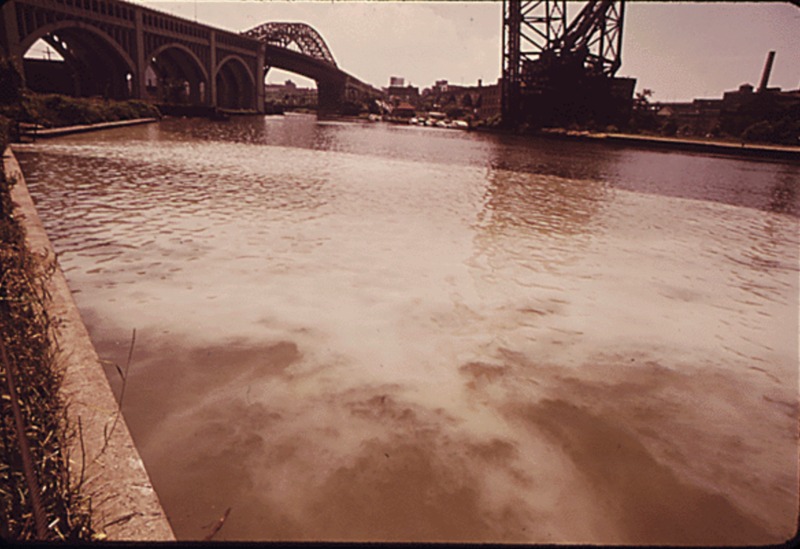

Public pressure and grassroots activism ensured that environmentalism would move to the the forefront of the liberal agenda in the 1960s during the Kennedy and Johnson administrations, which promised to improve the quality of life of all Americans and enacted several early federal laws. After President Richard Nixon took office in 1969, the burgeoning environmental movement and its allies in Congress demanded even more aggressive action and more comprehensive regulation. Several major events that year contributed to a widespread sense of "environmental crisis," including the Santa Barbara oil spill and the burning of the Cuyahoga River in Cleveland. Liberal Democrats sponsored the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969, which required an environmental impact assessment before approval of government and corporate development projects and allowed citizen activists and environmental groups to file lawsuits against prominent polluters. Richard Nixon reluctantly signed the legislation and promised to launch a national crusade to protect the environment, although environmental activists often criticized his administration for failing to back up its strong words with tough enforcement against corporations. Environmental politics also became central to the anti-Vietnam and New Left movements on college campuses, as the decade of activism in the 1960s set the stage for the Earth Day teach-ins and demonstrations that inaugurated the mass environmental movement of the 1970s.

Sources:

Chad Montrie, The Myth of Silent Spring: Rethinking the Origins of American Environmentalism (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2018), 1-24

Chad Montrie, A People's History of Environmentalism in the United States (New York: Continuum, 2011)

Adam Rome, The Genius of Earth Day: How a 1970 Teach-In Unexpectedly Made the First Green Generation (New York: Hill and Wang, 2013)

Adam Rome, "'Give Earth a Chance': The Environmental Movement and the Sixties," Journal of American History (September 2003), 525-554

"A Century of Environmental Action: The Sierra Club, 1892-1992," California History (Summer 1992)

Rachel Carson, Silent Spring (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1962)

News and Information Services (University of Michigan) Photographs, 1946-2006, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

Philip A. Hart Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

DOCUMERICA: The Environmental Protection Agency's Program to Photographically Document Subjects of Environmental Concern, 1972-1977, National Archives, https://catalog.archives.gov/id/542493