Environmentalism and the Great Society

Environmentalism and 1960s "New Liberalism"

Liberal intellectuals and politicians helped to bring environmentalism into the political zeitgeist in the mid-1950s and early 1960s. They were responding to scientific experts' growing concern about the excesses of economic development as well as to the small-scale grassroots activism against pollution that was just beginning to emerge. For some political players like historian Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. and economist John Kenneth Galbraith, professors at Harvard who were influential in Democratic politics, environmentalism was part of a new liberalism. Galbraith outlined this new liberalism in his 1958 best-selling book The Affluent Society, which included a middle-class horror story about the dangers of environmentalism.

The family which takes its mauve and cerise, air-conditioned, power-steered, and power-braked automobile out for a tour passes through cities that are badly paved, made hideous by litter, blighted buildings, billboards, and posts for wire that should long since have been put underground. They pass into a countryside that has been rendered largely invisible by commercial art... they picnic on exquisitely packaged food from a portable icebox by a polluted stream and go on to spend the night at a park which is a menace to public health and morals. Just before dozing off on an air mattress, beneath a nylon tent, amid the stench of decaying refuse, they may reflect vaguely on the curious unevenness of their blessings. Is this, indeed, the American genius?

In a just a few lines, Galbraith managed to capture growing concerns about the environment and spread the message to a larger audience as part of the new liberal agenda. However, the new message had more to do with the imbalance between the private wealth and public poverty that had emerged after the Second World War than it was about the environment specifically. In a 1956 essay, Schlesinger wrote "Our gross national product rises... consumer goods of ever-increasing ingenuity and luxuriance pour out of our ears, but our schools become more crowded and dilapidated, our teachers more weary and underpaid, our playgrounds more crowded, our cities dirtier, our roads more teeming and filthy, our national parks more unkempt, our law enforcement more overworked and inadequate." This new brand of liberalism entered the White House in 1960 with the election of John F. Kennedy.

The Kennedy administration undertook several steps that increased environmentalism's profile as a political issue. The administration organized a White House Conference on Conservation in 1962 with the help of Stewart L. Udall, the Secretary of the Interior. The conference gave conservation advocates from around the country the chance to interact with cabinet officials, the congressional leadership, and the President and Vice President. President Kennedy delivered the keynote address in which he described the conference as a single step forward in a long journey. The focus of conservationists was to search for a way to manage natural resources in a way that did not harm the environment. "It is a matter which involves not only all the people of this nation, but in a very real sense, all of the people of the world... Our great contribution..." said Kennedy, "is applying the great discoveries of science to this question of conservation."

In addition to the White House conference, Kennedy embarked on a 5 day, 11 state speaking tour to plug conservation to a national audience. As a first-year senator from Wisconsin, Gaylord Nelson wrote a memo urging the President go on this tour, in which he said the interest in conservation transcended "party lines, economic classes and geographical barriers... all that was missing was political leadership." The tour was met with a less than desirable public and media response. In response to the increased public attention on pesticides that resulted from Rachel Carson's Silent Spring, Kennedy ordered a report on toxic chemicals from his science advisors. However, JFK's presidential and environmental legacy was cut short by his assassination in 1963. The newly inaugurated President Lyndon B. Johnson was committed to finishing the work of his predecessor and establishing an environmental legacy of his own.

Lyndon Johnson and the United Auto Workers

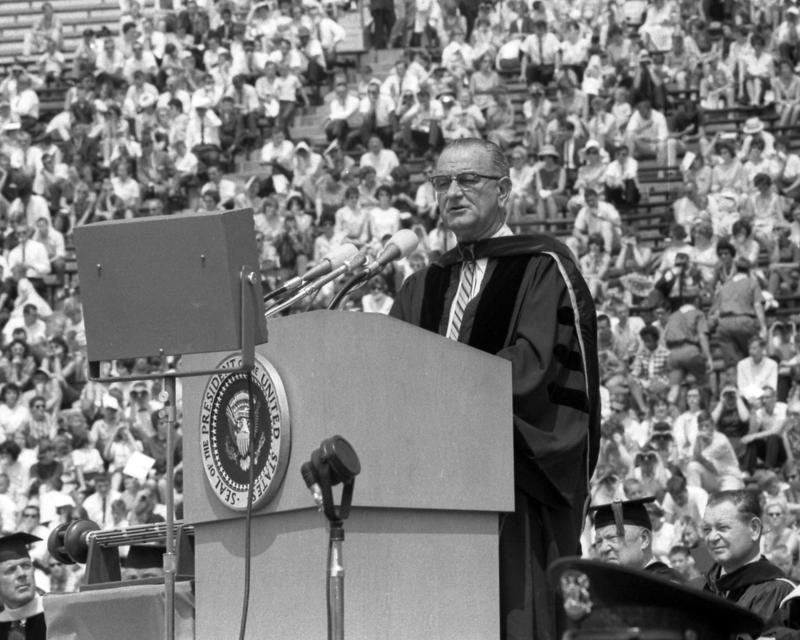

On May 22, 1964, President Lyndon B. Johnson delivered his famous “Great Society” speech at the University of Michigan’s commencement ceremony. The address is best known for Johnson’s endorsement of the civil rights movement and preview of the War on Poverty, captured in his pledge that the Great Society "demands an end to poverty and racial injustice, to which we are totally committed in our time." But the president also made a third commitment to the cause of environmental protection, part of the growing liberal focus on "quality of life" issues in the 1960s. He lamented the decay of the crowded urban centers and the "despoiling of the suburbs," the traffic jams on the highways and the disappearance of open land:

We have always prided ourselves on being not only America the strong and America the free, but America the beautiful. Today that beauty is in danger. The water we drink, the food we eat, the very air that we breathe, are threatened with pollution. Our parks are overcrowded, our seashores overburdened. Green fields and dense forests are disappearing. . . . Once our natural splendor is destroyed, it can never be recaptured. And once man can no longer walk with beauty or wonder at nature his spirit will wither and his sustenance be wasted.

In his U-M speech, Johnson called for a new approach by the government and citizens alike to build a Great Society where “man can renew contact with nature,” which “honors creation for its own sake,” where “our material progress is only the foundation on which we will build a richer life of mind and spirit.” The Michigan Daily reported “thunderous applause” from the crowd of 80,000 people at the football stadium and even described the president’s speech as a “non-political mission,” a questionable verdict at best. During his presidency, Johnson ordered federal agencies to make environmental quality a higher priority, commissioned a White House Conference on Natural Beauty, and signed nearly three hundred conservation laws to address air and water pollution and protect national parks. While these measures were modest compared to the environmental policies of the early 1970s, the “achievements of the Great Society were critical in the evolution of the environmental movement,” according to historian Adam Rome. Most of all, Lyndon Johnson’s actions set a precedent that the federal government bore responsibility for tackling the problems of pollution and protecting quality of life against unrestrained growth.

On May 24 and 25, 1965, President Lyndon B. Johnson held “the White House Conference on Natural Beauty” at the State Department. Many people were unfamiliar with environmental issues plaguing the country and “mistook the conference to be a search for a new Miss America or new varieties of roses.” At the conference, a series of panels discussed the Great Society’s role in restoring beauty to the American landscape as well as environmental issues of the day. More than one thousand people attended the conference, including Walter Reuther, the president of the United Auto Workers. In his remarks, Reuther stated, “to me, this conference is about how we build a tomorrow in which we can have not only more bread, but also more roses. Satisfying our material needs is a very simple thing with our advanced technology, but if we stand committed almost exclusively to the expansion of man’s material well-being and neglect his spiritual well-being, then I think we will fail to achieve that “Great Society.”

The United Auto Workers (UAW) strongly supported the liberal environmental agenda of the Great Society, an alliance that has largely disappeared from mainstream accounts of the modern environmental movement. UAW President Walter Reuther sat on the stage when Lyndon Johnson delivered the Great Society address at the U-M commencement and soon launched an anti-pollution environmental initiative through the union. In 1965, the UAW organized a "United Action for Clean Water" conference in Detroit, where Reuther called for a "great citizen crusade" to fight for clean air and clean water in addition to civil rights and anti-poverty programs "to create a total living environment worthy of free men." In 1967, the UAW established a Department of Conservation and Resource Development to promote anti-pollution programs, including restrictions on car emissions opposed by the Big Three automakers, because union members had to "breathe the same air and drink and bathe in the same water" as other Americans.

At this 1967 congressional hearing on air quality, the UAW stated its position that "no one has the right to pollute our environment" and labeled the "deterioration of our natural resources . . . a national disgrace." Walter Reuther also endorsed the Earth Day demonstrations in 1970, and the UAW then joined the Urban Environmental Conference, which focused on environmental justice campaigns in polluted inner-city areas and hazardous workplaces. According to Olga Madar, the head of the UAW's environmental campaign, "the chief victims of pollution are the urban poor, blacks and workers who cannot escape their environment. . . . Unless we join together now to stop those who pollute for profit, our cities will soon become ugly cesspools of poisonous pollutants.”

Sources for this page:

Bentley Image Bank, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

John Kenneth Galbraith, The Affluent Society (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1958)

John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, https://www.jfklibrary.org

Public Papers of the Presidents, 1963-1964

Lyndon B. Johnson, "Remarks at the University of Michigan," May 22, 1964, Lyndon B. Johnson Presidential Library, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x4Qc1VM80aQ [public domain audio recording]

Michigan Daily Digital Archives

Genevieve Gillette Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

Adam Rome, The Genius of Earth Day: How a 1970 Teach-In Unexpectedly Made the First Green Generation (New York: Hill and Wang, 2013), 16-20

Chad Montrie, The Myth of Silent Spring: Rethinking the Origins of American Environmentalism (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2018), 2-5, 107-110