Air Quality Politics in Michigan

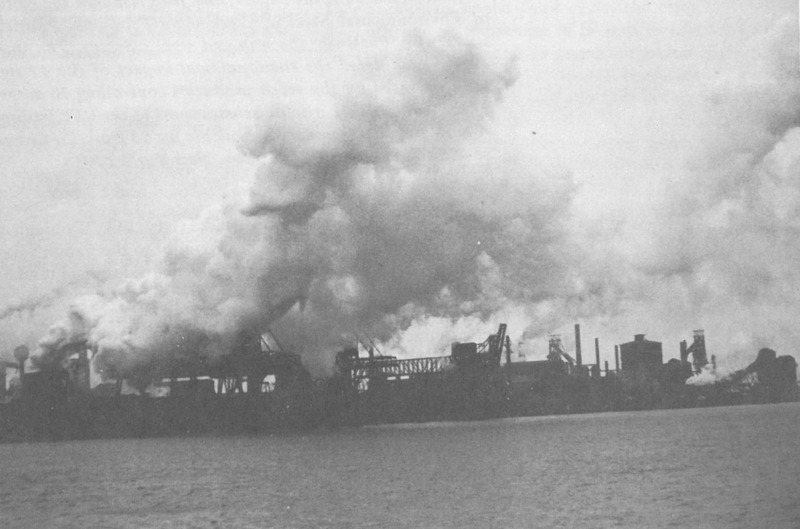

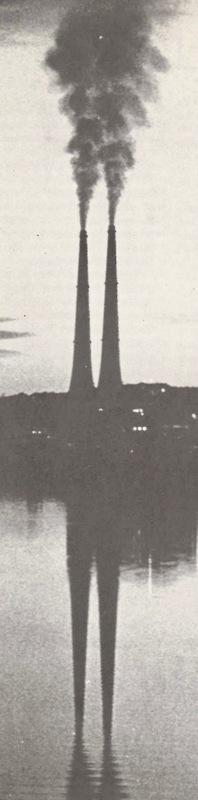

Throughout the 20th century, Michigan's economy grew with its industries. But because its industries had operated largely without environmental regulation, the state faced a conflict between its economic interests and citizens concerned about air pollution. In the 1950s and early 1960s, Michigan communities became concerned about pollution’s effects on public health and the health of the environment and several organized local air pollution control organizations. In response to public concern, the Michigan legislature passed Act 348 of 1965, the state’s first major air pollution control law. It created the Air Pollution Control Commission, a nine-member board with representatives from industry, government, and the public, to make and enforce rules to regulate air pollution.

As the above collection of letters from concerned citizens to Senator Philip Hart demonstrates, neither local air pollution organizations nor the state Air Pollution Control Commision was able to address industrial pollution in a way that satisfied the public. A father wrote the first letter, expressing concern about air pollution. “My wife fears the children’s play outside. I feel guilty starting my car… Twenty-six days in December we could not at noon see the sun in Battle Creek, why?”

In other letters, Michigan residents appealed to Hart for specific action because they found state and local air pollution control measures to be inadequate. Waterford Township resident Mrs. Joseph P. Guzak sent the second letter to Senator Philip Hart in 1966 to explain how the pollution produced by the Pontiac Motors Foundry had affected her community. “One can not breathe safely within miles of this Foundry. The homes, stores, and water towers are always filthy. They are painted every six months. Women cannot hang out their laundry to dry.” She urged Senator Hart to support stricter air pollution control measures at the federal level.

The third letter chronicles the efforts of a local pollution control organization to address the pollution produced by the Michigan Sugar Beet Company plant in Caro, Michigan. The writer described that “Caro pollution is far the worst in our county,” and asked Hart to pressure the State Health Department to force the sugar plant to adopt pollution control measures because “the Lansing crowd just will not listen to our problems.”

The final letter came attached to a petition signed by members of a neighborhood in Ecorse, a working-class community south of Detroit, who had “banned.. together to protest the tremendous amount of air pollution and industrial fallout in our area.” After the Ecorse city government refused to do anything about coal dust expelled by a nearby lumberyard, the neighborhood had appealed to the Wayne County Air Pollution Control Commission. After receiving the neighborhood's petition, Senator Hart sent the Commission a letter on their behalf and the Commission responded, reporting that it had investigated the problem and approached the lumber company with a plan to suppress the coal dust.

These citizens’ fears about air pollution and their frustrations about the options available to them reflect the ineffectiveness of air pollution control in Michigan prior to the Clean Air Act. Solutions at the state and local level were fragmented and concerned citizens were often powerless against industry. Many hoped that the 1970 Clean Air Act would solve these problems by setting federal standards and mandating state enforcement.

After the Clean Air Act of 1970 became law, Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Administrator William Ruckelshaus contacted Governor Milliken to coordinate Michigan’s plan to implement its requirements. In this letter, Ruckelshaus informed him that the state would need to enforce federal emissions standards, issue air quality permits to industries, and monitor sources of pollution. The regulations created by Act 348 of 1965 and the Air Pollution Control Commission were central parts of Michigan’s implementation plan for the Clean Air Act of 1970. However, Act 348 would need to be amended to fully satisfy federal standards.

On July 8, 1971, House Bill 4260, the bill written to amend Act 348, passed the state House of Representatives with a vote of 68 to 23. The bill would strengthen the previous air pollution control law by increasing the Commission’s authority, creating a fee paid by polluters to fund air quality surveillance equipment, and increasing the daily fine against industries that violated its standards from $100 to $10,000. After its speedy passage through the House, H.B. 4260 stalled in the Senate’s Health, Social Services, and Retirement Committee for nearly a year.

The Michigan Senate had been responsible for delaying many of the hundreds of environmental bills proposed after Earth Day, something the Senate Majority Leader argued was necessary because the House was too enthusiastic about conservation issues. The West Michigan Environmental Action Council lamented the state of environmental legislation in their April 1972 newsletter, writing that "NO good environmental legislation has been passed in almost two years," and that "Senator Hart's prediction once industries knew the environmentalists could win there would be a strong lobbying-adverting backlash, has come true." While the Senate delayed the bill, it was rewritten and weakened, which State Representative Raymond Smit attributed in the Detroit Free Press to the “‘Cozy relationship’ between [the committee] and large firms, including Detroit Edison Company, Chrysler Corporation, and the Dow Chemical Company.”

Facing the failure of yet another piece of environmental legislation, Michigan’s environmental activist groups rallied behind the stronger version of H.B. 4260. The League of Women Voters of Michigan issued action alerts to their members asking them to pressure their state senators, warning if the House version did not pass, the process might need to start over with a new bill. More significantly, “there [was] a strong possibility that the Environmental Protection Agency [would] not accept Michigan’s State Implementation Plan” in which case the EPA could implement its own rules.

Support for H.B. 4260 extended to the University of Michigan’s campus: in a letter to the Michigan Daily, an environmental law student wrote that “the Environmental Law Society, Ecology Center and ENACT [had] organized a petition drive in an attempt to force action on the strong House version, instead of allowing the Senate Committee to emasculate it.”

According to the guidelines set in the Clean Air Act, Michigan had until July 31, 1972 to present the EPA with a plan that satisfied federal air standards. Despite the best efforts of environmental activists and supportive legislators, Michigan failed to pass H.B. 4260 in time. Following this, the Detroit Free Press reported that Administrator Ruckelshaus judged Michigan's plan inadequate on the grounds that it had "failed to make emissions data available to the public and failed to provide for proper control of nitrogen oxide emissions." Representatives of Detroit Edison and Dow Chemical, as well as the Wayne County Air Pollution Control Commissioner, opposed this judgment, arguing that the EPA's testing methods were inaccurate and the EPA's standards would limit some kinds of pollution while increasing other kinds. Despite their objections, the EPA imposed its own plan.

As Michigan's struggle to produce an acceptable plan demonstrates, the passing of the Clean Air Act was only the start of the US's path to cleaner air. In the years that followed, Michigan and other states needed to create measures to enforce the law's regulations. Industries often resisted state and federal regulation, but citizen activists remained vigilant, mobilizing to protect air pollution control laws.

Sources

Philip A. Hart Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

William G. Milliken Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

West Michigan Environmental Action Council Records, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

League of Women Voters of Michigan Records, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

Environmental Action Newsletters

Detroit Free Press, April 23, 1972

Detroit Free Press, July 20, 1972